Between Boosters and Backlash, a ‘Non-Conversation’ over Philadelphia Energy Hub

Part two of a two-part series. The first article gave an overview of the energy hub idea’s rapid progression.

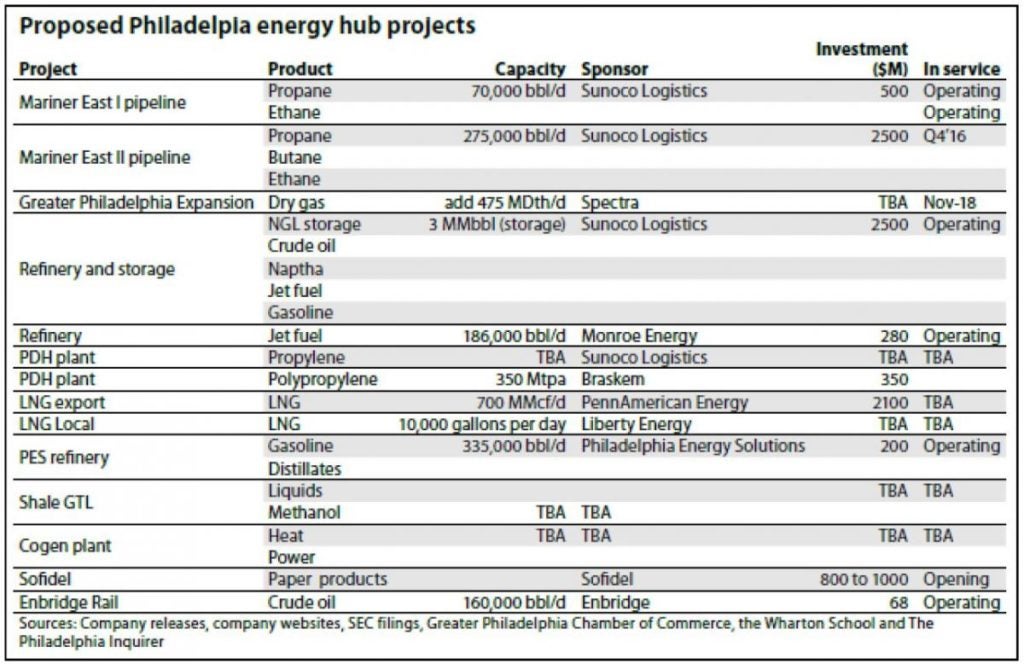

The nascent Philadelphia energy hub makes a compelling economic case: Take advantage of cheap natural gas and liquids from the Marcellus Shale and build factories and refineries to produce plastics, paper, chemicals, steel and glass, all the while rejuvenating a manufacturing base that has been dying for decades.

But many people in and around the city reject that argument, reasoning that the vision of an energy hub is myopic — that any long-term bet on fossil fuels lengthens their deleterious effects on air, water and the global climate.

The tension is growing harder to resolve as companies and public officials decide whether and how to flesh out this vision of a multibillion-dollar energy complex along the Delaware River.

Lisa Crutchfield has advocated policies to help Duke Energy Corp. and PECO Energy Co. and has served on the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. These days, she is selling the Philadelphia energy hub.

“We have proximity to other major markets that are a benefit for us,” the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce’s senior vice president of advocacy and public affairs said in an interview. “There are some fairly large brownfield sites where you can benefit from being close to Braskem, close to PBF [Energy] and close to Bucks County — Dow’s up there. You’d want to be in this region.”

She ticked off more reasons: “Regional proximity, as well as the ability to be close to the feedstock. … Cost of transport. … Henry Hub right now is $3, $3.07[/Mcf], and the gas coming out the Marcellus’ Leidy Hub is about $1.40, so there’s a significant commodity price differential. We’re hoping that with the commodity price differential and shorter distance for transport, it will be economically more attractive.”

‘Overproduction and Overconsumption’

The energy hub’s opponents have a list of concerns ranging from direct environmental impacts to socioeconomic ripples.

“The Sierra Club thinks that expanding the refinery and dirty fuel infrastructure in and around the city of Philadelphia is a poor use of our riverfront land, our labor resources, our rail line infrastructure, capital and the fragile health of at-risk communities,” said the group’s Philadelphia conservation chair, Jim Wylie.

“Any jobs gained from a short-term investment would be at the expense of public health, environmental impact and a missed opportunity to train people for a sustainable and clean industry,” he said.

The biggest offender, in Wylie’s estimation, is the old Sunoco LP refinery, which was “saved” with a purchase by the Carlyle Group LP-backed Philadelphia Energy Solutions Refining & Marketing LLC.

Wylie said he does not think Philadelphia needs to be saved in quite that fashion. In 2012, the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery released 762,390 pounds of toxic chemicals, according to the U.S. EPA, 98% of all of south Philadelphia’s toxic emissions. Wylie warned, “So if the refinery were to double in size …”

Environmental activist Iris Marie Bloom of Protecting Our Waters, a thorn in the side of Marcellus Shale gas producers in the state for years, has even more basic objections to more fossil fuel use.

“The [Sunoco Logistics Partners LP] Mariner East I and II pipeline projects are a great example of the tremendous waste involved in using economic resources to increase climate change and air pollution and water pollution by bringing fracked NGLs 300 miles across the state to export these NGLs, such as ethane, overseas from the Delaware River,” Bloom said.

“This kind of overproduction and overconsumption of fossil fuels is expensive to our economy in that it further retards the commitment we need to sustainability,” Bloom added. “The shale energy hub represents a direction for Philadelphia which is diametrically opposed to the vision of a clean, healthy, vital and green future Philadelphia.”

Project developers can be surprised by the organized opposition the environmental community can muster in the Philadelphia region, said Andrew Levine and Catherine Ward, co-chairs of the Philadelphia law firm Stradley Ronon Stevens & Young LLP’s environmental practice.

“Proponents weren’t prepared for the level of resistance,” Levine said. “Having said that, it’s a very technically weak opposition, but very passionate nevertheless. And so it’s really a question of demonstrating to the decision-makers that while environmentalists have a lot of passion, there’s not much science behind their concerns.”

The Mediator

Stepping between the sides is Mark Hughes, director of the newly formed Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Formed with a $10 million donation in 2014 by Apollo Global Management LLC partner Scott Kleinman and his wife, Wendy, the center seeks to craft innovative energy policy that is fair to all stakeholders.

Hughes was an adviser to the outgoing Philadelphia mayor, Democrat Michael Nutter. He also wrote the city’s Greenworks sustainability plan, a document with comprehensive goals of reducing energy use in all parts of the city and increasing the power generation from alternative sources.

“In terms of the non-conversation that’s happening now, it’s got two problems: People are not actually talking to each other. They are talking past each other, at best,” Hughes said of the discourse around the energy hub.

“The Chamber is boosterish, optimistic, and largely in reaction to that, you have this kind of building mobilization in the environmental community that is opposed to that vision,” said Hughes, who is also a professor at the Ivy League school.

Hughes plans on leading a convocation of stakeholders from all sides of the issue starting in October.

“The plan is for it to meet four times beginning in October and wrapping up in January, with a shared vision the diverse group can all stand behind,” Hughes said.

“A Philadelphia energy hub worth having will require a voluntary process among civic-minded parties capable of advancing all the important issues at stake,” Hughes wrote in an April call-to-action essay.

“Choosing among alternatives involves making tradeoffs among competing objectives and being exposed to those tradeoffs through discussion with other stakeholders,” he wrote. “Nothing about the energy hub discussion to date sounds even remotely like the above. Boosters and doomers talking without listening have more in common with an Eagles game than with a facilitated process of structured decision-making.”

He concluded: “But that process may be the only way to make real progress toward a Philadelphia energy hub worth having.”

The full article, published with permission from SNL Financial.