Targeted Demand, Targeted Supply: Decarbonizing Private Aviation First

Private aviation could jump-start the market for truly carbon-negative jet fuel. By targeting a small group of high-end users, California can connect direct-air-capture carbon with waste-biomass hydrogen to produce sustainable aviation fuel—helping to decarbonize the skies faster than offsets ever could.

Aviation accounts for roughly 2.5% of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions. Without mitigation, that share could double by 2050. Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) can cut lifecycle emissions, but they cost two to ten times more than conventional jet fuel. This piece outlines a near-term pathway to carbon-negative SAF via the Fischer-Tropsch (FT) process using CO2 captured from air and hydrogen from sustainable biomass.

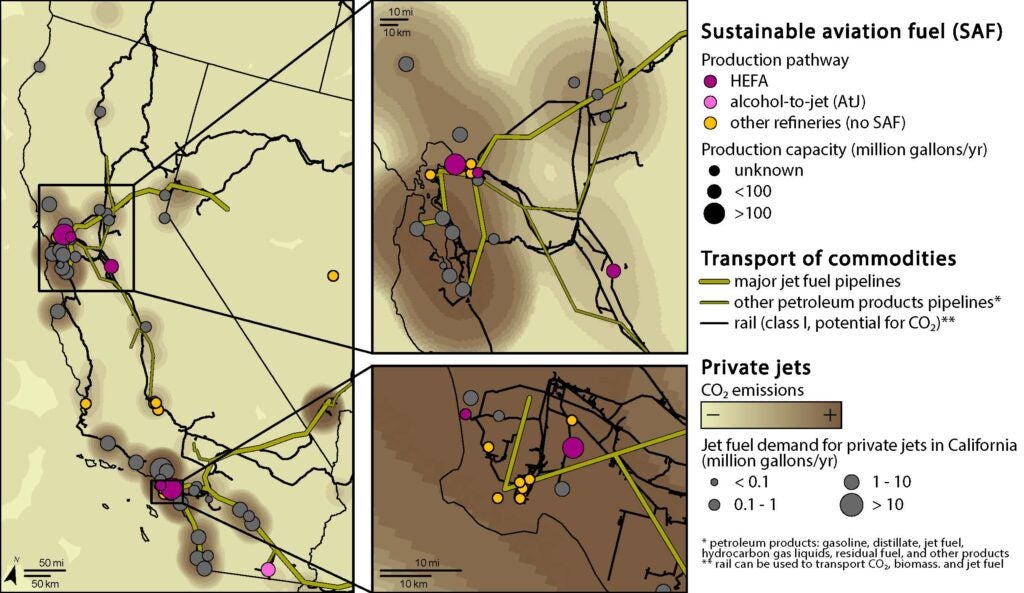

Starting with private aviation. To tackle aviation emissions, we should start with business and charter flights. These concentrate demand at a handful of airports and serve customers able to pay a premium. Many already buy carbon offsets, which vary widely in quality and rarely deliver durable, verifiable climate benefits. Redirecting that spending to high-integrity SAF offtakes can help scale production and lower costs. Philanthropic and corporate buyers can play a big role as first movers.

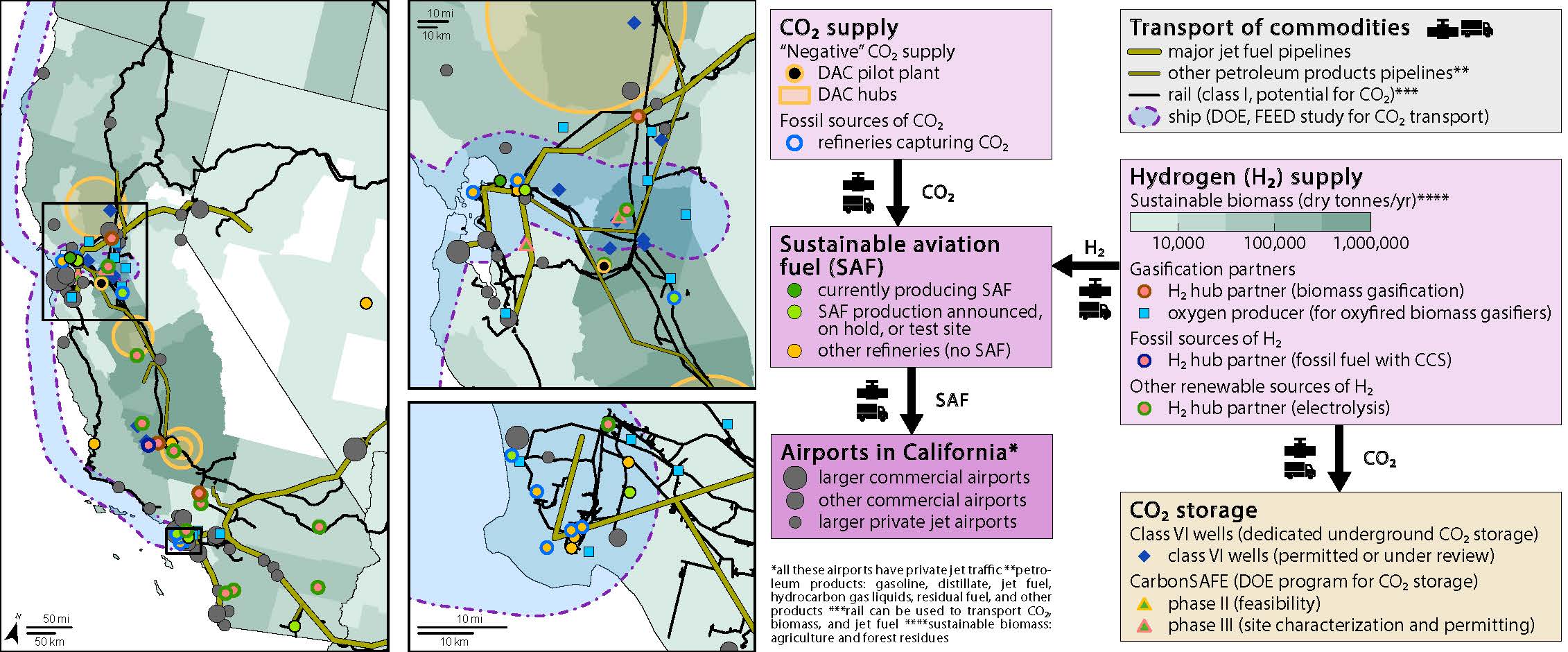

California as proving ground. We can also start where demand is concentrated. The Bay Area and Los Angeles are the perfect proving grounds: with ambitious climate targets, clean-fuel incentives, and refinery conversions (like Phillips 66 Rodeo, Chevron El Segundo). The region’s logistics—pipelines, ports, and rail—enable efficient feedstock and fuel transport (see Figures 1–2).

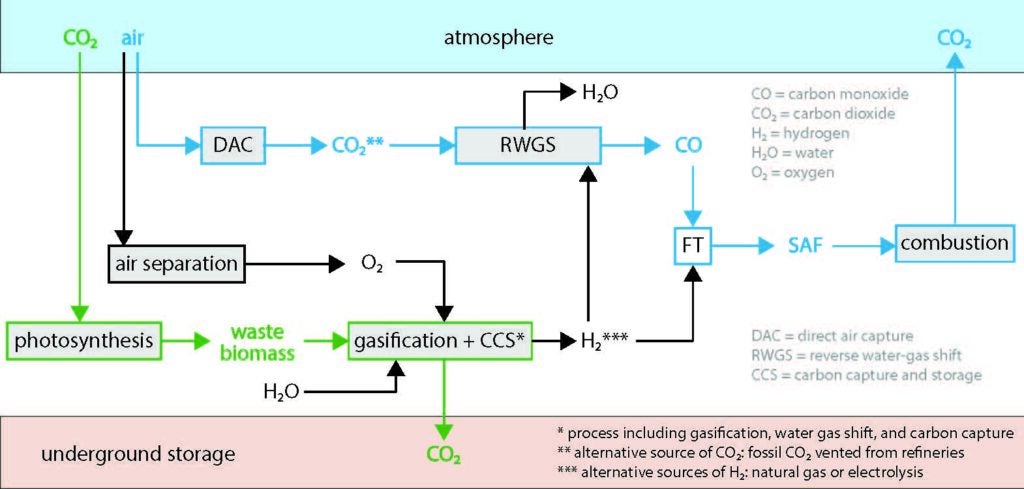

The pathway. FT synthesizes hydrocarbons from CO + H2. To stay fossil-free, CO2 from air is converted to CO via reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) using hydrogen from biomass gasification with CCS (see Figure 3). The CO2 captured from air becomes part of the fuel and returns upon combustion, while the biogenic CO2 from gasification is stored. When stored carbon exceeds lifecycle emissions, the fuel is net-negative. FT yields several products; the diesel-range fraction is upgraded to SAF.

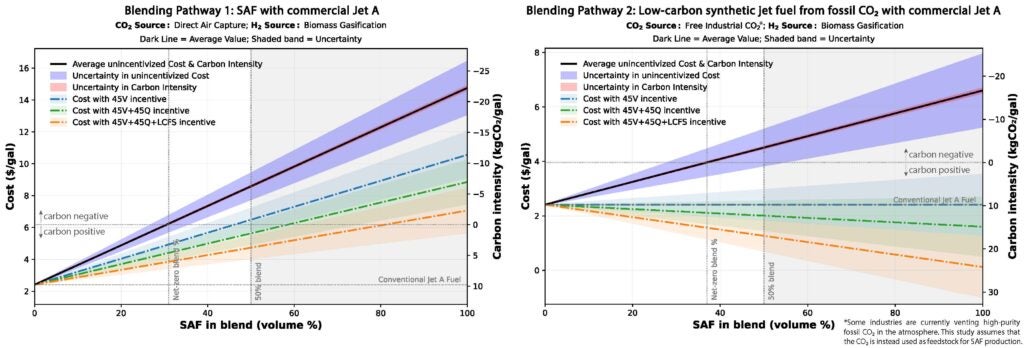

Activating the market. In the near term, FT-SAF production can use hydrogen from refineries with CCS (blue hydrogen), electrolysis, or high-purity CO2 streams now vented at refineries. While carbon negative FT-SAF production is ramping up, it can be blended with conventional jet fuel to progressively lower its carbon intensity at a small cost (see Figure 4). Under current ASTM D7566 specifications, FT-SAF can be blended up to 50 percent with conventional jet fuel (Jet-A) for commercial use—a threshold likely to expand as certification advances.

Economics and policy. Today, conventional jet fuel averages around $2 per gallon. Early FT-SAF will certainly carry a premium, but federal and state incentives can help close the cost gap. For example, California’s LCFS and federal 45Q, 45V, and 40B / 45Z credits reward verified lifecycle reductions. 40B applies through 2024, transitioning to 45Z in 2025. Each can pair with LCFS but not with each other.

Globally, CORSIA (the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) sets standards for lifecycle accounting, meaning FT-SAF that meets these criteria can qualify for both compliance and voluntary markets. Premium-priced, multi-year offtake agreements from private aviation and philanthropic buyers can further accelerate deployment. Concentrated demand at a few airports simplifies logistics and enables targeted infrastructure: DAC and gasification co-located with refineries, oxygen supply, and Class VI wells for CO2 storage.

Next steps. Three actions can build momentum:

- secure multi-year offtakes for carbon-negative SAF at key private-aviation airports

- develop regional “SAF hubs” co-locating DAC, biomass-to-hydrogen, FT units, and storage (e.g., Bay Area, Kern County)

- ensure rigorous monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV)

Though focused on California, we can use this model wherever biomass, storage, and low-carbon power align. Private-aviation and philanthropic leadership can accelerate circular jet fuel—using atmospheric carbon to make fuel rather than offset emissions.

Hélène Pilorgé

Research Associate, Clean Energy Conversions LabHélène Pilorgé is a research associate with the University of Pennsylvania’s Clean Energy Conversions Laboratory. Her research focuses on carbon accounting of various carbon management solutions and on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping for responsible deployment of carbon management.

Shrey Patel

PhD Candidate, Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringShrey Patel is a PhD candidate in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on the integration of carbon dioxide removal with low carbon energy sources.

Greg Cooney

Senior FellowGreg Cooney is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center. He previously served as director of the policy and analysis division in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Carbon Management.

Makenna Damhorst

Undergraduate Seminar FellowMakenna Damhorst is a third year student in earth and environmental science. Damhorst is also a 2025 Undergraduate Student Fellow. She conducts research with the Clean Energy Conversions Laboratory.

Jennifer Wilcox

Presidential Distinguished ProfessorJen Wilcox is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering and Energy Policy. She previously served as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the Department of Energy.