One-third of the world’s population lacks access to clean cooking and approximately 733 million people have no access to electricity. A global transition to sustainable energy cannot be achieved unless women are equally included as leaders, partners, and beneficiaries.

At a Glance

Key Challenge

Gender dimensions were not included in the original template for the energy compacts, which made it difficult to assess stakeholders’ actions toward gender equality and sustainable energy transition.

Policy Insight

To close gender gaps in the energy sector, we must position women as agents of change in the transition process, instead of simply users. In addition to strategic commitments, organizations must make financial commitments to their gender and energy activities, and continuously review their progress.

Introduction

Unprecedented changes have been observed in global climate patterns. Time and time again the world has been warned by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the approaching climate disaster that will befall us if civilization does not immediately change course. To aggravate the situation, the global community faces interlinked energy, food, and financial crises compounded by the COVID pandemic. These challenges impact marginalized and vulnerable groups, with many developing countries being particularly at risk.

The importance of Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7), which aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all, cannot be over-emphasized during such trying times. Research has shown that achieving SDG 7 is an essential step toward the achievement of other Sustainable Development Goals, including those related to gender equality, poverty reduction, health, job creation, climate, and the environment.

Gender dimensions are key for sustainable energy and highlighted by UN Women. SDG 7 is one of only six of the seventeen SDGs with no gender-specific indicators. Billions of women around the world still lack access to basic fundamental rights including access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy. Striving to close this gap is instrumental in developing a just and inclusive energy transition. It has become imperative to understand the critical role women play in SDG 7 and the Paris Agreement goals (United Nations 2021c).

Ensuring gender equality is not only a precondition of securing human rights but is also considered a smart economic priority. As stated by the High-Level Dialogue Ministerial Theme Reports on Energy Access and on Enabling SDGs through Inclusive, Just Energy Transitions, accelerating the integration of gender-transformative approaches into all energy access and transition pathways is required to close gender gaps and empower women by ensuring gender parity in employment and strategic decision-making processes (United Nations 2021a.b). Therefore, investing in the economic empowerment of women must be a major priority across all energy access transition strategies. This begins with recognizing and acknowledging women as leaders in innovation in the energy sector (United Nations 2021c).

Against this backdrop, The International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy (ENERGIA), Global Women’s Network for the Energy Transition (GWNET), and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), are co-leading a Gender and Energy Compact to catalyze action toward gender equality and women’s empowerment to accelerate a just, inclusive, and sustainable energy transition.

Purpose of Study

Gender equality, energy access, and advancing climate action are inextricably linked. There are manifold gains that can be achieved across the board if they are all addressed together. However, there are several barriers that prevent a level playing field for women and prevent them from equally benefiting from the clean energy transition.

One demonstrative example of this is the fact that SDG 7 is one of just six SDGs with no gender indicator. This impacts policymakers’ capacity to make evidence-based decisions due to a lack of data. Without gender indicators, it is difficult for stakeholders to commit to effective gender action. Hence, a gender baseline study supports taking stock of where we stand in terms of gender ambitions in the voluntary energy compacts that, in the long run, will help in the achievement of SDG 7 and the Paris Agreement goals.

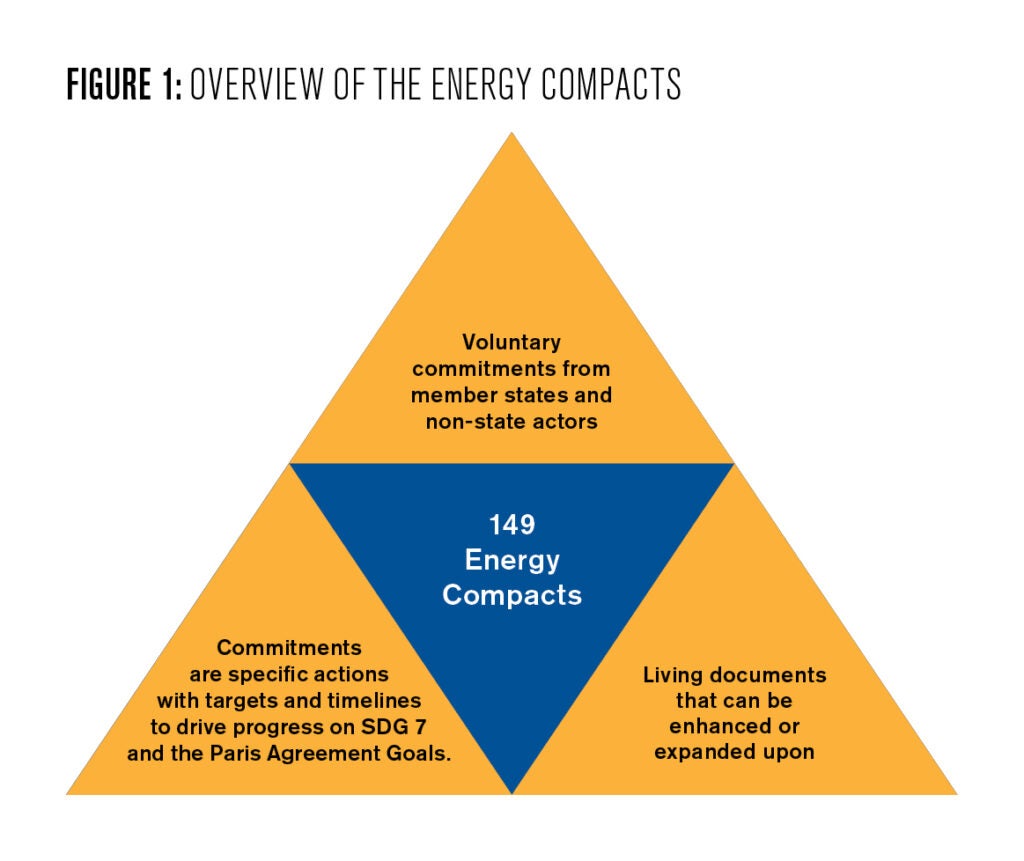

As part of the mobilization to achieve SDG goals by 2030 and Net Zero Emissions by 2050, UN Energy is working as an intermediate body in bringing together UN international organizations and multi-stakeholders, to develop and implement their commitments in the form of “Energy Compacts”—voluntary commitments to specific actions to accelerate progress on energy access, renewable energy and energy efficiency (United Nations n.d.). These compacts act as an inclusive umbrella to bring together voluntary commitments to achieve SDG 7 targets, which are in line with all SDG goals by 2030 and Net Zero emission by 2050.

This digest outlines the key findings of the gender baseline assessment of the energy compacts. The assessment has been carried out to take stock of the gender sensitivity of the submitted voluntary energy compacts. The assessment encompasses the 149 energy compacts available on the UN Energy website at the time of analysis (July 2022).

Gender Baseline Assessment

Not reflecting gender dimensions in the energy compacts is a missed opportunity to achieve sustainable energy and a just and inclusive energy transition for all. Hence, establishing a baseline on the status of the energy compacts in terms of their gender sensitivity contributes to the achievement of SDG 7 and the Paris Agreement goals.

The primary goal of undertaking this assessment was to identify and categorize the 149 energy compacts based on their gender sensitivity, to take stock of where we stand, and further inform the Energy Compact Action Network on the gender status of these compacts.

The assessment is not an evaluation but a tool to create awareness and a baseline on how we can make energy compacts more equitable and inclusive. It establishes a benchmark for future assessments against which progress can be measured and provides an opportunity to follow up with stakeholders on how they view their compacts in terms of the degree of gender sensitivity and inclusion presented in the commitments that have been submitted. In summary, the baseline reflects on whether gender has been prioritized as a key target statement across these compacts and identifies and highlights the best examples to guide stakeholders on re-establishing their gender targets and outcomes.

Methodology and Process

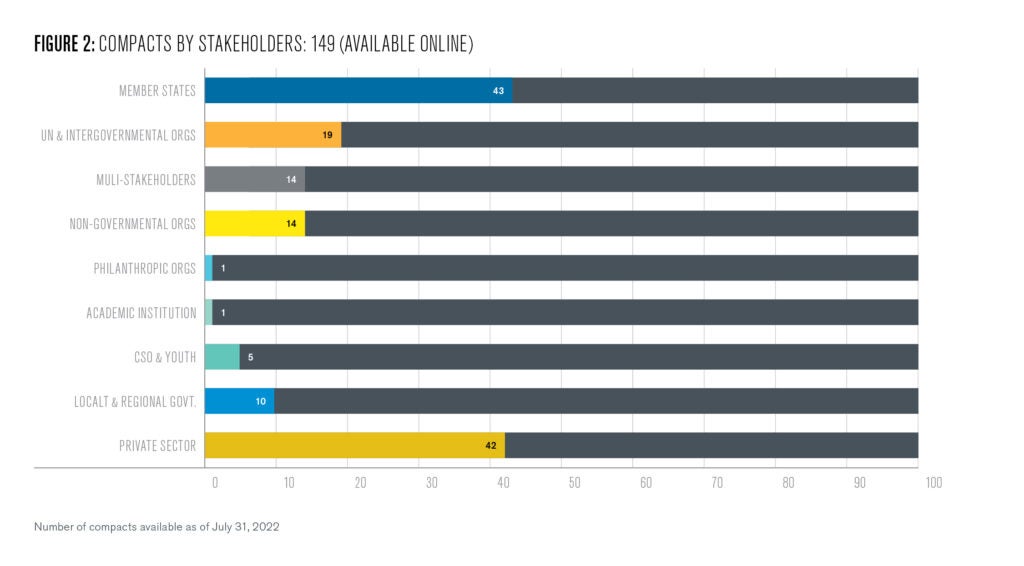

All available energy compacts have been submitted by member states, intergovernmental organizations, multi-stakeholders, NGOs, philanthropic and academic institutes, members of the private sector, as well as local and regional government bodies.

A standard template is available to all stakeholders to showcase their ambitions, action plans, monitoring mechanisms, and financial investments to achieve SDG 7 targets. The format of the template submitted by the stakeholders is available on the UN Energy website. Preliminary analysis found that it was difficult to access the gender aspect from the template. The template failed to take into account gender inclusivity as an essential step in achieving SDG 7. Keeping this in mind, a two-step analysis was carried out to measure the level of gender sensitivity adopted by each stakeholder in their commitments.

The two-step analysis included the categorization of the energy compacts and a keyword analysis.

Categorization of Energy Compacts

The aim of categorizing each energy compact is to provide a comparative opportunity between the self-assessment of stakeholders and their objective assessment. Additionally, it provides an opportunity to follow up with stakeholders on how they view their compacts and the assessment of gender sensitivity. The categorization of the energy compacts is based on the level of gender sensitivity, which have been defined based on the requirements provided in the Energy Compact 2022 Progress Template and presented by UN Energy.

The below categorizations have also been reflected in the UN Energy Progress Report Update Survey for stakeholders to fill in and report on the progress of their energy compacts. The sections mentioned have been derived from the Energy Compact 2022 Progress Template.

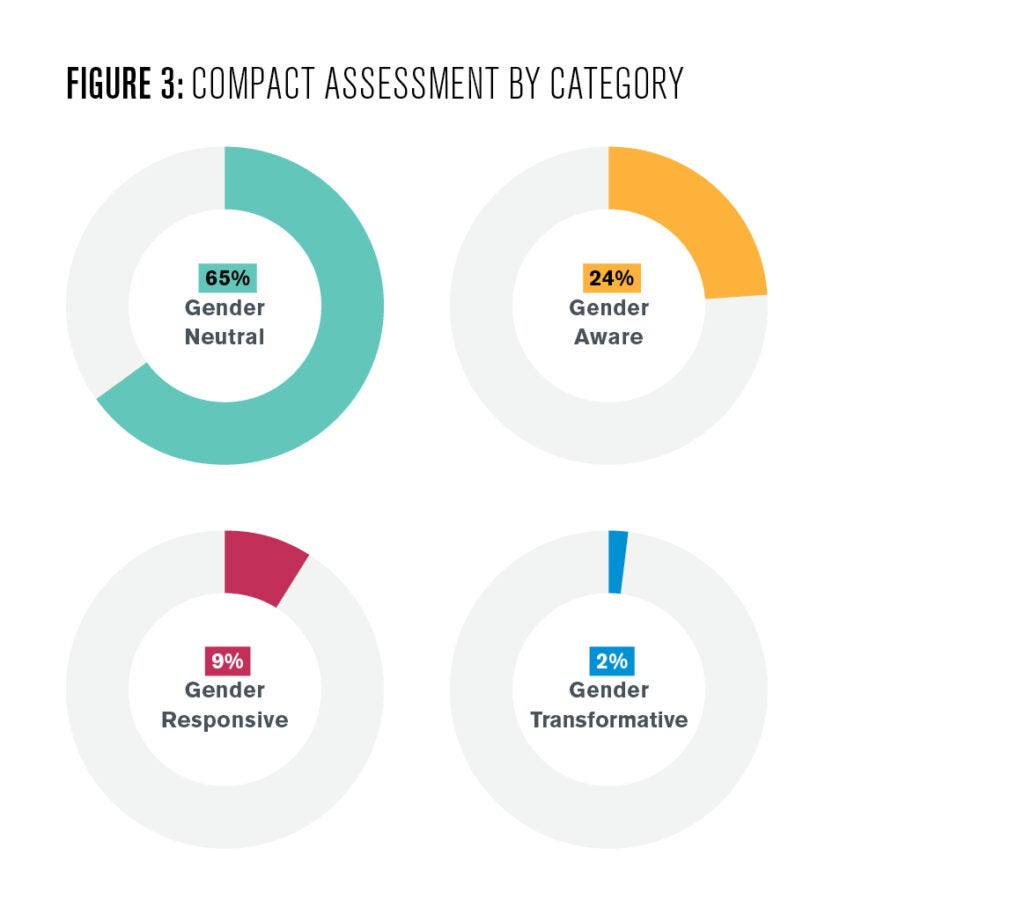

- Gender Neutral: Contains no explicit or intentional mention of gender or women in the energy compact.

- Gender Aware: Explicitly or intentionally addresses a gender issue(s) and mentions differentiated energy needs of women and men in both the context for the ambition(s) [Section 1] and the guiding principles [Section 7.IV].

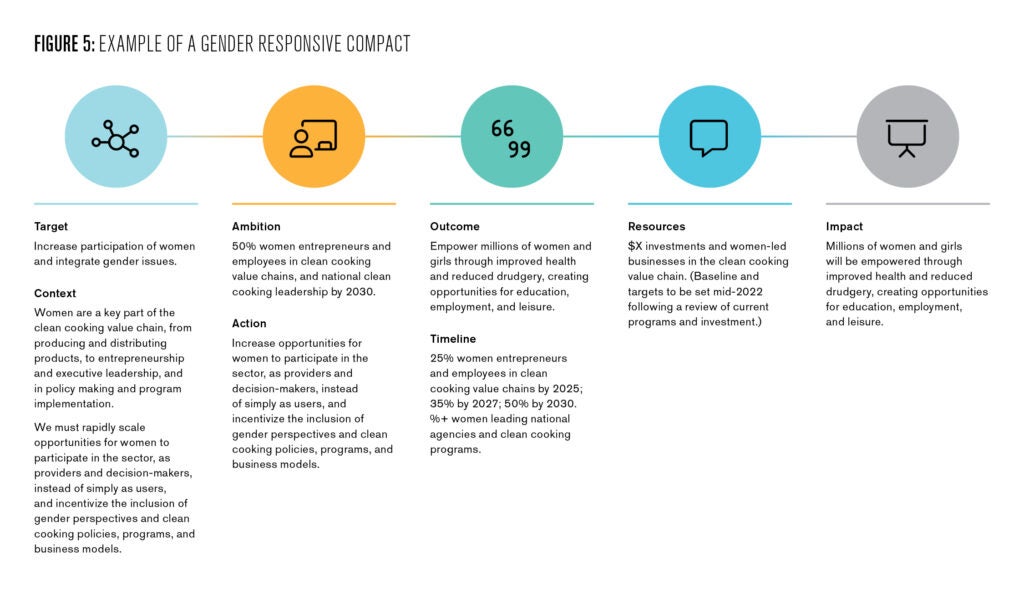

- Gender Responsive: Explicitly or intentionally describes gender actions [Section 2] to address the gender issues and needs identified in the context and specifies related gender targets in the ambition with related timeframe [Section 2 and 1].

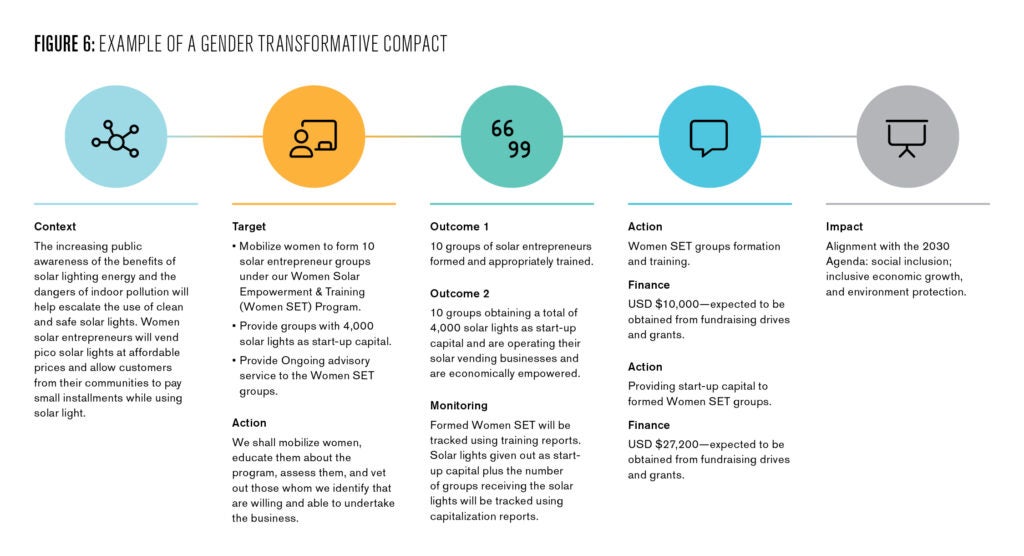

- Gender Transformative: Explicitly or intentionally describes a time-based and measurable gender outcome(s) [Section 3] related to the gender action that contributes to women’s strategic interest; allocates required finance and investments for the implementation of the action [Section 4]; and includes gender as an accountability variable to monitor and report on the progress of the gender outcomes [Section 6].

Out of the 149 energy compacts available online, only 141 were accessible and followed the template guidelines. Therefore, the final categorization was carried out on these 141 compacts to ensure uniformity.

Each compact was classified into one of the above defined categorizes. Out of the 141 energy compacts assessed, 65% were Gender Neutral, meaning that they did not have any explicit or intentional mention of gender in their commitments. 24% of the compacts assessed were found to be Gender Aware, i.e. the energy compact identified gender issues and understood the differentiated energy needs of women and men as part of their ambition or targets. Only 9% of energy compacts were identified to be Gender Responsive, while only 2% of the 141 energy compacts analyzed were Gender Transformative.

In order to understand the difference between a compact being gender responsive and gender transformative, it is necessary to understand that the former only provides an action plan for the gender targets set, while the latter takes into account the strategic needs of the women by going a step beyond gender responsive and includes specific gender outcomes, monitoring mechanisms to measure these outcomes, and financial investments required to achieve gender inclusivity goals. Gender transformative actions view women as decision-makers rather than merely end users in the energy supply chain.

The analysis also showcased the distribution of various stakeholders across each gender-sensitive category. It was found that the highest number of gender-neutral compacts came from the private sector and member states, which were also the two stakeholder categories that submitted the highest number of energy compacts.

The same trend occurred within the gender aware category. Only 13 compacts were identified to be gender responsive, with the member states and non-governmental organizations showcasing the highest contribution to this category. Only three energy compacts were identified to be gender transformative, one from a member state, one from an NGO, and one from a CSO and youth organization.

Keyword Analysis

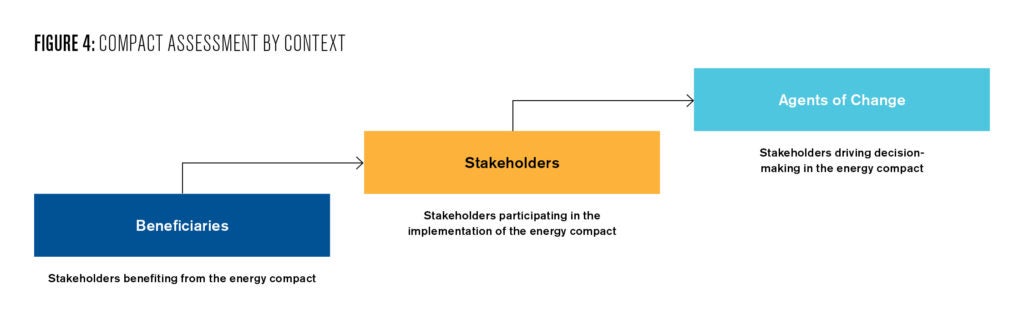

The main idea behind conducting a keyword analysis was to understand the context in which women are positioned in the energy compacts. The analysis involved first searching for keywords in the energy compacts. Words included: gender, female, females, women, woman, girls, or girls. The next step was to understand the context in which women and girls were mentioned either as beneficiaries, stakeholders, or agents of change.

Data Extraction Process

For each energy compact, a search was conducted for the keywords “gender, female, females, women, woman, girls or girl.” Every energy compact was thoroughly read for descriptions or statements which loosely suggested or were associated with these keywords. Once a keyword was found within the document, the next step was to extract all information to understand the context in which that keyword was used and ultimately to classify how these energy compacts positioned women as part of their gender targets. For example, all Gender Neutral compacts did not mention any of these gender keywords.

The results from the keyword analysis are as follows:

- Nearly one-third of the energy compacts mention at least one of the following gender-related keywords: gender, woman, women, girl, girls, female, females.

- Out of the compacts that mention any of the gender-related keywords, 56% position women as “beneficiaries.”

- Only 15% position women as key stakeholders participating in the implementation of the energy compacts.

- Nearly 29% of the energy compacts with related gender keywords, position women as “agents of change” that are driving the decision-making in the energy compacts.

To enable stakeholders to re-evaluate their commitments, two examples are highlighted in this digest as Gender Responsive and Gender Transformative (see Figure 5).

In the above examples, an energy compact that was identified to be Gender Responsive failed to be identified as Gender Transformative as no specific financial commitments or resources were allocated for activities related to gender equality and women empowerment. There is a small gap between the two categories, because stakeholders must properly establish financial commitments, monitoring mechanisms, and outcomes, in order to be classified as Gender Transformative.

Overall Key Observations

- Of the 141 energy compacts reviewed, nearly 65% were Gender Neutral. Of the remaining one-third that included gender considerations women were mostly represented as beneficiaries, but seldom as agents of change.

- Of the compacts that included gender considerations, the majority come from member states (39%).

- Only 2% of the compacts allocated specific financial resources for their gender actions.

- The energy compacts that were categorized as Gender Responsive failed to be identified as Gender Transformative because no specific financial resources were allocated for the implementation of their gender actions.

Limitations of the Assessment:

- Gender was not included in the original template for the compacts.

- There was inconsistency in the way the template was filled out by stakeholders.

- Not all compacts are available on the UN’s website (*as of July 31st).

Recommendations

In order to close gender gaps in the energy sector, UN Energy Compacts can be a powerful tool to develop gender-sensitive, responsive, and transformative actions. Energy Compact Action Network members should be encouraged to apply a gender lens in their compacts and position women as decision-makers, driving climate action and the advancement of SDG 7. This can be achieved through the following actions:

- Include a gender dimension in the Energy Compacts Template.

Gender is at the heart of achieving SDG 7 goals. It is a well-established fact that a gender-inclusive approach to energy is critical for a just and inclusive energy transition. In the last one year, the Gender and Energy Compact signatories increased to 75, including nine Champion Countries1 with as many as 17 gender equality focused organizations. Going forward, stakeholders must reformulate and adopt more inclusive and gender-responsive energy access and transition strategies and policies.

- Encourage energy compacts to position women as agents of change, as the most inclusive and transformative approach.

Currently, women do not have a high presence in the energy industry. This is due to many factors, including lack of opportunities, difficulty in reconciling family and work life, stereotypes that define the house responsibilities as being exclusive to women, lack of safe working environment free of gender violence and sexual harassment, lack of female models in management positions, and barriers to education. Therefore, focus needs to shift towards increasing career opportunities, investment in local business, and wealth creation opportunities for women in the clean energy value chains. Policies must foster an enabling, inclusive and safe institutional working environment for women to enter and advance in the energy workforce.

Clean and sustainable energy transitions are mostly seen as a global solution to problems of climate change mitigation. But these discussions also have an important social component, as they can support a more equitable development model, through which social gaps are addressed, and greater opportunities for social and economic growth are generated. Since women and men interact differently with existing energy technologies and have differentiated levels of access, knowledge, and decision-making authority, it is necessary to include a gender approach in energy policies, institutions, and projects in order to better respond to the needs and interests of women.

- Recognize women as providers and decision-makers in the energy transition process, instead of simply as users.

Women are a key part of the clean energy value chain. They must participate not only as energy users but as providers and decisionmakers. Therefore, we must rapidly scale opportunities for women to broadly participate in the sector—as service providers, entrepreneurs, and executive leaders—and incentivize the inclusion of gender perspectives in energy policies like clean cooking programs and business models. Several compacts have defined increased participation of women in the energy sector at various positions as one of their key target ambitions. Some have also set aside financial resources for accelerating the adoption and use of clean cooking technologies and fuels by both rural and urban households in the coming years.

- Encourage concrete financial commitments to achieve gender and energy activities.

Although many stakeholders had a target aiming to enhance the strategic position of women in the energy industry, many failed to provide any specific financial commitments to support these goals. This was mainly due to the fact that energy transitions and gender are not seen in the same frame. Stakeholders must broaden their perspective on applying a gender lens to energy data, to accelerate gender-transformative progress toward achieving SDG 7 goals.

- Increase the involvement of various stakeholders from diverse sectors, including gender organizations and women-led businesses.

This baseline assessment revealed that most of the compact commitments were submitted by member states and the private sector. More players from diverse backgrounds must be encouraged to take part in this gender transformative progress. Women-led and women-owned businesses must be targeted by enhancing both public and private investments for productive use of energy activities.

- Continuous self-evaluation must be conducted by stakeholders to help them re-define their commitments in order to become ender Transformative.

There is a need to review compacts through an open dialogue, which will help stakeholders scale up their commitments, share their best-practices, and effectively respond to challenges. Self-evaluation must be conducted on a continuous basis to keep up with new global initiatives and challenges. New forms of impact-oriented business models and investment practices can be adopted by studying the best practices being followed by others.

The summary findings of the gender baseline assessment have directly contributed to making the reporting on the energy compacts submitted by different stakeholder groups to UN Energy more gender sensitive. A section of the findings was published in the Energy Compacts Annual Progress Report 2022.

Naimat Chopra

2022 Kleinman Energia FellowNaimat Chopra is pursuing a master’s degree in social policy and data analytics at the School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2). She is the 2022 Kleinman Energia Fellow.

ESMAP. 2022. “2022 Tracking SDG7 Executive Summary.” https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/data/files/download-documents/sdg7-report2022-executive_summary.pdf.

Gender and Energy Compact. n.d. https://genderenergycompact.org/compact/

Prebble, M. and A. Rojas. 2017. Energizing Equality: The Importance of Integrating Gender Equality Principles in National Energy Policies and Frameworks. IUCN Global Gender Office. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/iucn-egi-energizing-equality-web.pdf

Skutsch, M.M., Joy Clancy, and Hanke Leeuw. 2006. The Gender Face of Energy: A Training Manual Adapted to the Pacific Context from the ENERGIA Commissioned Training Manual. Bulletin of The European Association for Theoretical Computer Science – EATCS. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242558197_The_Gender_Face_of_Energy_A_Training_Manual_Adapted_to_the_Pacific_Context_from_the_ENERGIA_Commissioned_Training_Manual

United Nations. 2021a. Theme Report on Energy Access: Towards the Achievement of SDG 7 and Net-Zero Emissions. High-Level Dialogue on Energy Ministerial Thematic Forum. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/09/2021-twg_1-091021.pdf

—. 2021b. “Enabling SDGs through Inclusive, Just Energy Transitions Towards the Achievement of SDG7 and Net-Zero Emissions.” https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021-twg_3-b-062321.pdf.

—. 2021c. “Multi-Stakeholder Gender and Energy Compact: Catalyzing Action towards Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment to accelerate a Just, Inclusive and Sustainable Energy Transition. https://genderenergycompact.org/assets/2022/02/31Jan2022_Multi-Stakeholder-Gender-and-Energy-Compact_lr.pdf

United Nations. n.d. “United Nations Energy Compacts Registry.” UN Energy. https://www.un.org/en/energycompacts/page/registry.

- The UN defines Global Champions as representatives from member states that spearhead advocacy, raise awareness, and inspire commitments and action on the five energy themes (access, transition, inclusivity, innovation and investment). They also play a key role in mobilizing voluntary energy compacts. [↩]