Investigating “Superblocks,” Barcelona’s Bid to Take the Streets Back from Cars

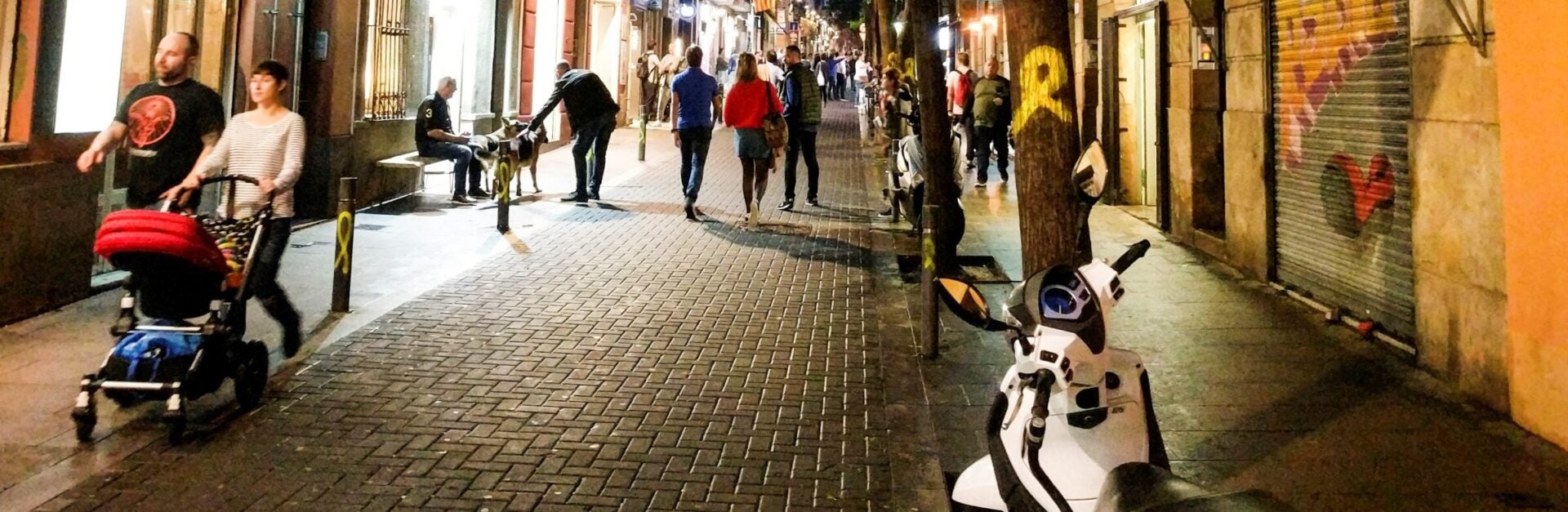

Barcelona is taking streets back from cars and creating walkable, mixed-use public spaces, or “superblocks.” Its plan is insanely ambitious. I went to see how it’s going.

When the Kleinman Center approached me last year about becoming a fellow and doing some travel reporting, I knew instantly where I wanted to go: Barcelona.

You’re probably thinking, “of course you wanted to go to Barcelona, everyone does!” But I didn’t just want to sit at sidewalk cafes, sip espresso, and watch the street life. (That was just a bonus.)

I wanted to go to Barcelona because it is in the early stages of implementing a grand, wildly ambitious urban plan that would see the city utterly transformed. If the plan is completely implemented—a big If, given the political cross currents—it would reclaim some 70 percent of the urban land now devoted to cars and give it over to walkable, mixed-use public spaces called “superblocks.”

Plenty of cities around the world are creating car-free zones, often in their centers, like Oslo and London. And plenty have car-free days or car-free events. New York City just announced congestion pricing in lower Manhattan.

But all these efforts are, in one way or another, rear-guard actions. They concede the larger reality: that the preponderance of surface area in big cities will be devoted to roads and parking for people in private vehicles.

Barcelona is after something different, and bigger. Recapturing over two-thirds of the land now devoted to cars and turning it over to people—people walking, biking, or just hanging out—would make it the world’s first plausibly “post-car” major city, a city where most land isn’t for cars and most people don’t have one.

That would be, among other things, an inspiration to the many other cities around the world beginning to push back against motor vehicles. (Greenhouse gases from transportation are rising, in the US and globally.)

I wrote a short blog post on superblocks back in 2016, when Barcelona had just implemented the first one, and ever since I’ve wondered how the program was progressing.

In October, I went to find out. I spent 10 days there, talking to city officials, urbanists, academics, and residents about the superblocks implemented so far and the expansive plans for more. What I found was captivating, a story with so many compelling threads and personalities that I couldn’t fit them into a single piece.

So I wrote five. The full series is rolling out on Vox this week.

(Well, technically I wrote six. In researching Barcelona, I fell down a rabbit hole and got so fascinated by its history that I ended up writing a separate piece on it.)

The idea for superblocks can be traced to Salvador Rueda, the city’s resident visionary. He worked in city government for decades, then, in 2000, started the Urban Ecology Agency of Barcelona, a public research consortium where he is still director.

His motivation is simple: his studies show that, to live with healthy levels of noise and air pollution, people must be freed from automobile through traffic. It’s that simple.

So he conceived of large areas—nine square city blocks, three by three (though the exact shape will depend on the neighborhood)—in which through traffic would be pushed out, routed around the periphery. Inside, resident and delivery vehicles would move at pedestrian speed. The streets would be public space, open to all, for a variety of uses, from sports to concerts to simple gathering space, with no fear of cars. Superblocks, or superilles in Catalan.

Somewhat unbelievably, the city took him up on it. It has adopted the slogan, “let’s fill the streets with life!”

Two superblocks have been implemented so far (one of which will quadruple in size this year). There are five more in some stage of implementation, at least three more in the queue, and beyond that, a plan for eventually (gulp) 500.

That is an eye-popping level of ambition, a more rapid and thorough transformation of urban space than is being contemplated by any other major city, certainly any U.S. city.

Among the many challenges ahead: municipal elections on May 26, in which the supportive mayor, Ada Colau, may lose her seat. What might happen to superblocks after that is uncertain. But support is spreading among Barcelona residents, as new neighborhoods demand them, so the program may have gained a momentum beyond politics.

Rueda envisions superblocks eventually becoming something like villages, semi-autonomous social units, with shared gardens, health clinics, and community events. He wants to use public space to reknit the social fabric, to make the city more healthy, sociable, and resilient against climate change.

Getting from two superblocks to 500 means dealing with short-term problems like politics, traffic, and gentrification. But the city is confident that the transformation underway has become unstoppable.

Read more from David Roberts about Barcelona’s superblocks on Vox, and watch for his upcoming policy digest on our carless future.

David Roberts

Energy and Climate Writer, VoxDavid Roberts is an energy and environmental writer with Vox and a former senior fellow at the Kleinman Center.