The Formative Effects of Gas Price Shocks

New research shows that experiencing a dramatic change in the price of gas can have a lasting impact on our transportation preferences.

With gas prices soaring, Americans certainly wish they were driving less. And many are. Right now, the push and pull of supply and demand makes all of us think twice before visiting the pump.

But one group of drivers will experience today’s price shock in a more enduring way: our recently published research predicts that teenagers learning to drive right now—15- to 18-year-olds—will drive less throughout their adult lives than cohorts before or after them. They will be more likely to commute to work on public transit and will be more likely to drive fuel-efficient cars.

Why? Our data shows that experiencing a dramatic change in the price of gas can have a more lasting impact on our preferences than we formerly thought. When these experiences occur during the “formative years”—in this case when most American kids learn to drive and first fill up their gas tanks—the impacts can last for decades to come.

Today’s gas price trends mirror some of the historic shocks we’ve previously analyzed. Case in point: the 1970s oil crises.

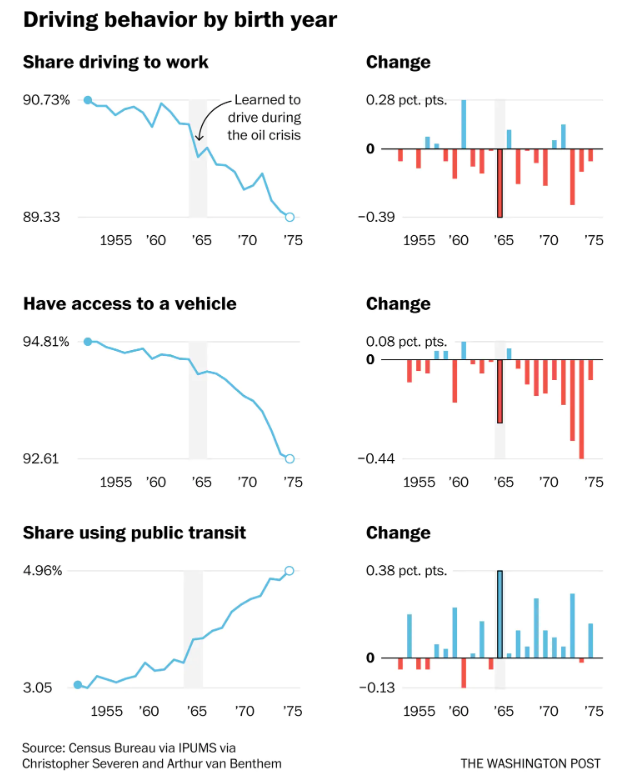

We found that individuals who experienced the surging gas prices of the 1970s during their formative driving years (around ages 15 to 18) appear less likely to drive to work 20 years later than the preceding and following cohorts. Our event study analysis puts the magnitude of this difference between 0.2–0.5 percentage points for the 1979 oil crisis. The effect is larger in magnitude in urban settings with transportation alternatives and for lower-income workers.

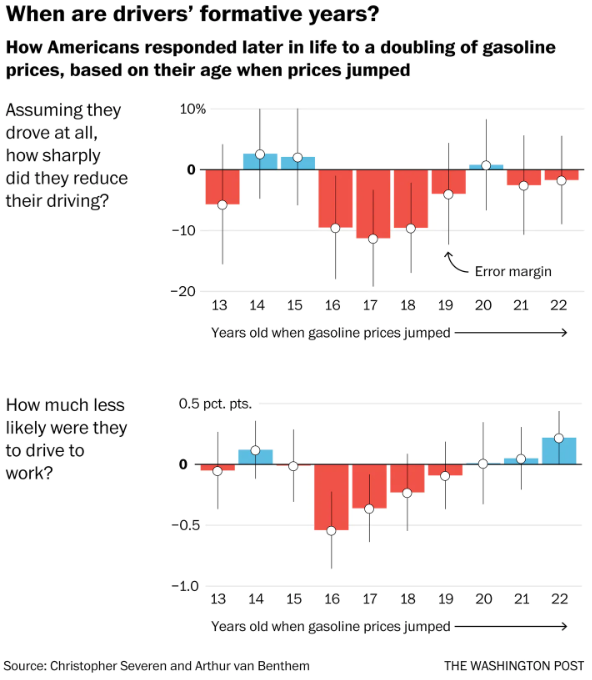

Combining several waves of a national travel survey, we show that intense price spikes experienced during formative years also decrease how much people drive. Teen drivers who experience a doubling of real gasoline prices (what many are experiencing right now in the United States) will drive 3 to 8 percent fewer annual miles as adults. Today’s new driver cohort, we predict, will also follow this pattern—driving less throughout their lives than those who learned to drive under less dramatic price spikes.

It’s important to clarify that it’s not the actual price of gas that affects this long-term behavior. It’s 1) the sharp change in the price of gas 2) during this formative moment of learning to drive. When prices have remained steadily low or high as teens learn to drive, we do not see an enduring shift in driving behavior. And we do not see a long-term shift in behavior for those who experienced the gas spike after these formative driving years.

Seeing any long-term shift in driving behavior, even a slight one, is significant considering that the share of Americans who drive to work remains pretty constant over the last 40 years—roughly 80%.

In other words, demand for driving is really inelastic here in the United States. But our study demonstrates a compelling margin of elasticity. From a policy perspective, one big reason driving in the U.S. is so inelastic is that quality public transport is lacking. For this and other price responses to manifest fully, we therefore need viable alternatives to driving.

What if transit were more frequent, reliable, and affordable—like in many European cities? We believe we would see even bigger effects from price shock events that occur during formative years. Furthermore, better public transport would increase the effectiveness of a whole suite of gasoline policies‚ such as a gas tax and fuel-economy standard—helping us reach our emissions goals sooner.

Christopher Severen

Senior Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of PhiladelphiaChristopher Severen is a Senior Economist in the Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. His research interests span urban, environmental, and development economics.

Arthur van Benthem

Associate Professor of Business Economics and Public PolicyArthur van Benthem is an expert in environmental and energy economics, exploring the economic efficiency of energy policy. He is a faculty fellow at the Kleinman Center and an associate professor of Business Economics and Public Policy at Wharton.