Shedding the Load: Power Shortages Widen Divides in South Africa

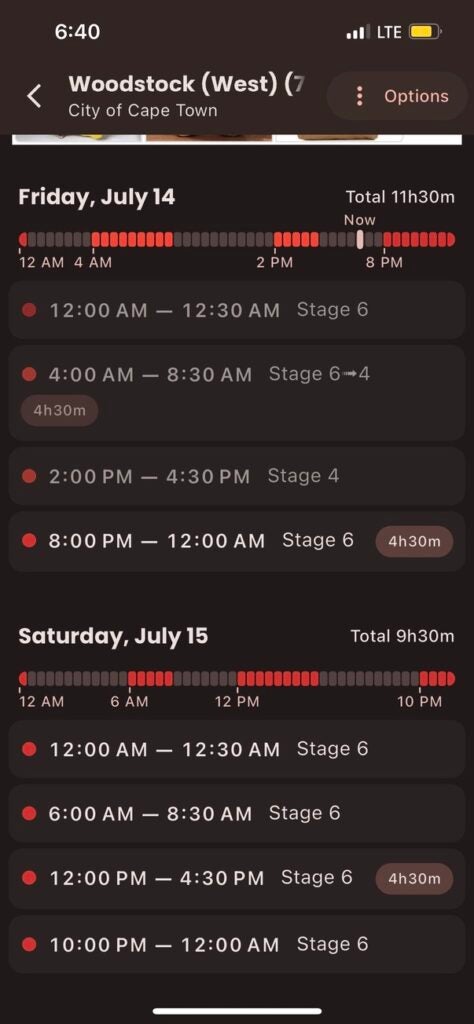

The typical American experiences less than 10 hours of power outages a year–whereas in South Africa, more than 10 hours of power outages were scheduled for just this past weekend.

“We have everything we need to supply power. The issues come down to corruption.” This is a common refrain you’ll hear among locals in Cape Town, South Africa as they try to explain the persistent “load shedding” (power loss) that occurs over several hours a day—with extremes of up to 12 hours a day without power.

This is the reality for a country of more than 61 million people, where an estimated 63% of the population lives below the poverty line. Load shedding is a series of rolling blackouts that occur across South Africa in various stages (stages 1-8) to prevent overloading the national power grid when the energy demand exceeds energy production.

The sole public electrical utility in South Africa, Eskom, which supplies 95% of the country’s electricity, has faced severe criticism for these conditions. In February 2023, the South African government agreed to take on $14 billion of Eskom’s debt, suggesting that this bailout would help protect the long-term prosperity of the country and allow Eskom to avoid default and make appropriate investments in better power solutions.

However, many argue that this bailout—coming after another already approximately $14 billion of debt relief over the last 15 years—absolves the utility of wrongdoing without addressing the root cause of the problem the way that breaking up the utility would.

It is unrealistic to attribute the nation’s decades-long struggle with energy infrastructure to solely one cause: corruption, sabotage, lack of investment, legacies of the apartheid regime, or mismanagement have all contributed to the problem. The country’s complicated and recent history with enforced racial segregation and social stratification during apartheid has left immense challenges. Many citizens rely on costly generators to preserve access to health care, education, water, and other economic activities—an expense that many South Africans simply cannot afford.

In 2022, South Africa was deemed the most unequal country in the world by the World Bank, with race still strongly correlated to inequalities in wealth, education, employment, and land almost three decades after the official end of the apartheid regime. Load shedding does not affect all equally. While those who can purchase generators or adjust schedules to accommodate the power cuts, those who can’t are left behind. The already unequal distribution of internet and technology is exacerbated by increased transportation costs, decreased access to home cooking, restricted education access, and employment risks that are associated with these rolling blackouts.

President Ramaphosa himself has acknowledged this problem. “South Africa’s energy security can only be assured if we reduce reliance on a single utility for power and unlock private investment in generation capacity,” as currently, the country’s power generation is extremely dependent on aging coal infrastructure. In November 2022, the World Bank approved $497 million for the Eskom Just Energy Transition Project, which aims to decommission a major coal-fired power plant, use this area for renewable energy generation, and prioritize job creation in the transition.

Some tie these institutional challenges with the perceived failures of the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) program. BEE is a post-apartheid policy that seeks to “bring the black majority into the economic mainstream,” but critics have argued that it fails to address the root causes of inequity in the country, leaving behind gaps in management and infrastructure that remain to be filled.

Regardless of the potential consequences of this policy, the root issue remains: aging, carbon-intensive infrastructure that risks being made obsolete by overuse or by the necessary renewable energy transition. If these issues are not addressed, the consequences to the South African economy, industry, and citizens will be detrimental.

The author explored this research through the Kleinman Center student grant program. Pursue your energy education with a student grant.

Arwen Kozak

Senior Research CoordinatorArwen Kozak is senior research coordinator at the Kleinman Center. She assists with research and programming initiatives at Kleinman, working to support visiting scholars, students, and grant recipients.