Energy System Planning: New Models for Accelerating Decarbonization

System planning is crucial for a successful clean energy transition that balances infrastructure transformation, reliability, and affordability. The U.K. recently overhauled its grid planning and operations through creation of a National Energy System Operator (NESO). This digest explores NESO’s pioneering model and lessons it offers for improving the U.S.’s fragmented and inefficient energy planning.

At A Glance

Key Challenge

A decarbonized energy system requires new and better means of system planning to keep it reliable and affordable.

Policy Insight

The U.K.’s new independent, state-controlled system planner that can operate across electricity and gas systems is a promising experiment in how to improve planning for the energy transition.

Introduction

Although it hardly strikes many as the most exciting topic, system planning is one of the key ingredients of a successful transition to clean energy. Planning will be essential for managing the necessary addition of massive quantities of clean energy infrastructure alongside the gradual winding down of old infrastructure, all while keeping the lights on, heat and air conditioning pumping, cars running, and bills affordable.

In the United States, our models of energy system planning are both (1) grossly fragmented, failing to take a whole-of-systems approach to the challenge; and (2) rife with possibilities for self-interest and self-dealing by those tasked with planning the system (Klass et al. 2022). These features create real risks of slowing the energy transition and overspending on it.

In contrast, the United Kingdom has recently proven an innovator in energy system planning. In 2024, the U.K. dramatically changed the way it runs and plans its energy system by creating a new public corporation, the National Energy System Operator (NESO). This new entity is charged with jointly planning and administering U.K. gas and electricity systems to achieve net zero as reliably and cost-effectively as possible.

This policy digest highlights the importance of the U.K.’s recent institutional innovations and suggests how they might offer a blueprint for energy system governance reform in the U.S. It first describes how the energy transition creates new imperatives for unbiased, whole-of-system energy planning. It then turns to the forces and politics that motivated U.K. energy planning reforms and the details of NESO’s institutional design. Finally, it considers how the U.K.’s policy experiment could be instructive in the U.S. federal and state contexts.

The Role of System Planning in the Energy Transition

Jurisdictions leading the way on responding to climate change have established aggressive goals to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. To facilitate whole-economy shifts away from carbon, many have recognized that electricity systems—as the backbone of national economies—must decarbonize even earlier, as soon as 2030 or 2035 (Labour Party n.d.; The White House 2024).

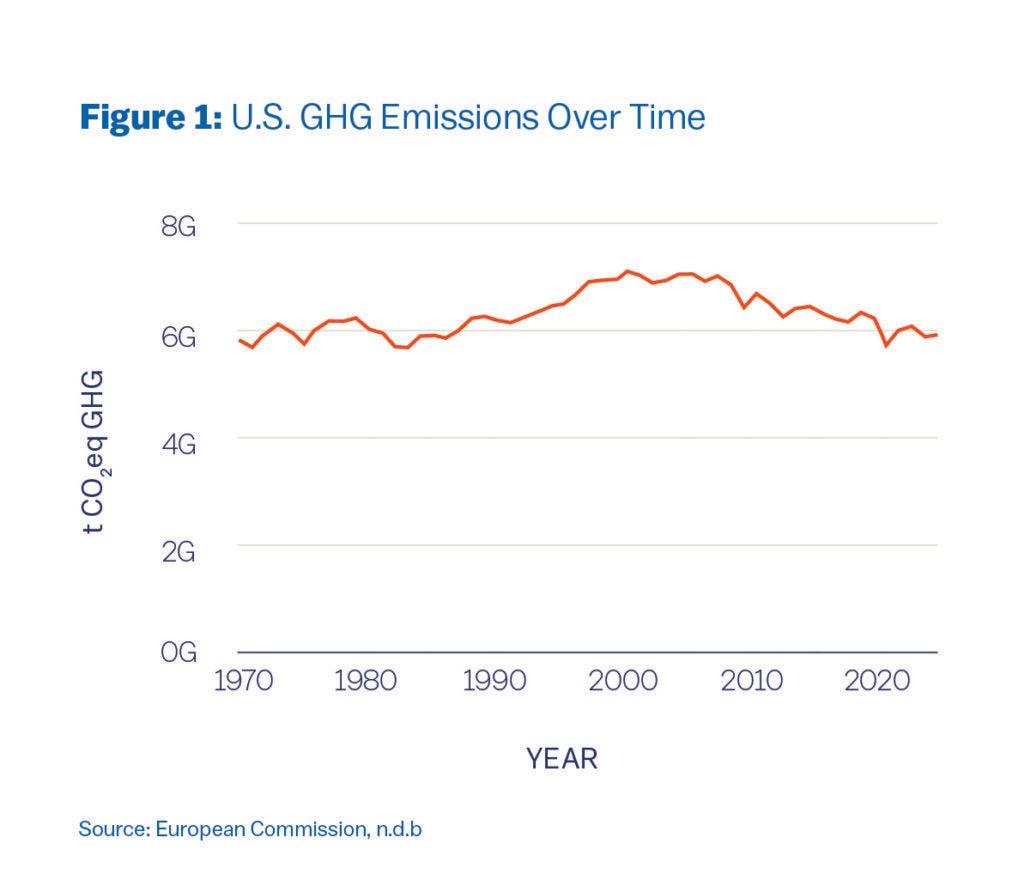

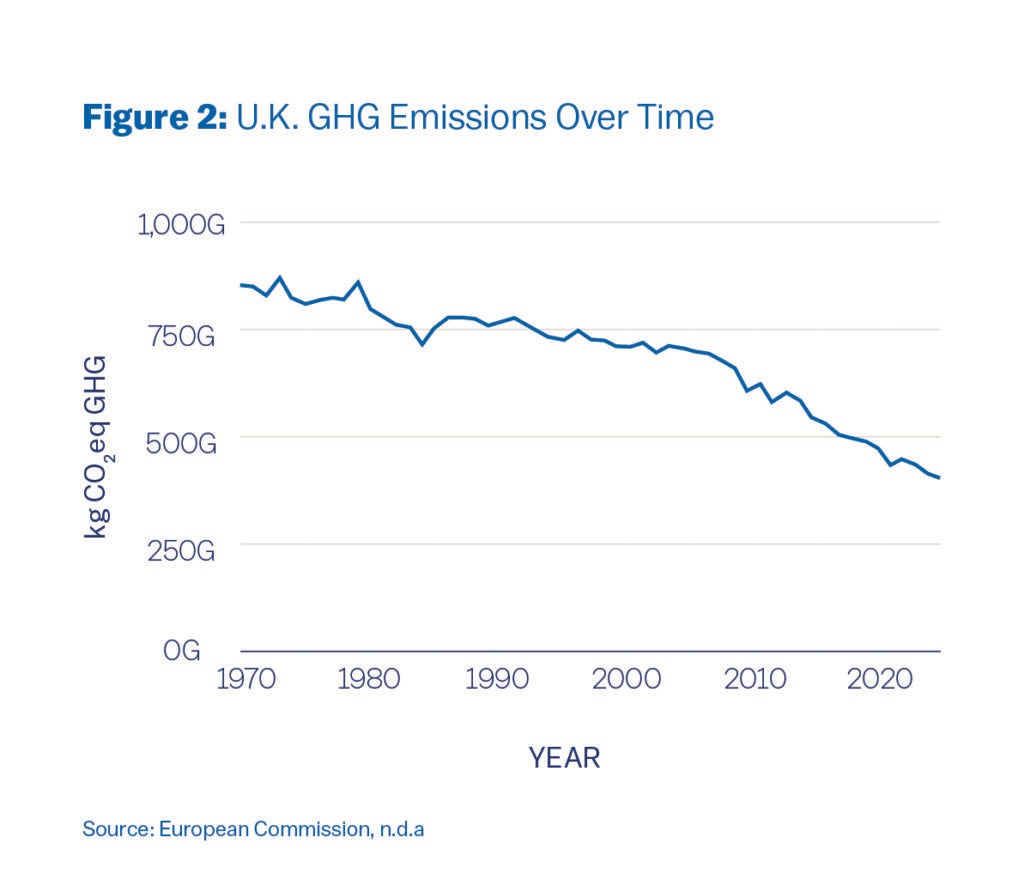

At present, both the U.S. and U.K. are in what scholars have described as the “mid-transition” (Gocke 2025; Grubert and Hastings-Simon, 2022)—partway to these goals with emissions falling from their peak, but with a long way yet to go (see Figures 1 and 2). Coal-fired electricity has become increasingly uneconomic, replaced instead by cleaner but still carbon-emitting gas generation.1 Renewable energy is becoming ever cheaper and more prevalent (Schipper and Hodge 2025). Electric vehicles (EVs) are steadily gaining a foothold in the transportation sector (IEA 2024).

To reach ambitious energy transition goals, these trends must be accelerated. Transmission and clean energy infrastructure must balloon, EVs and clean public transit must come to dominate the transportation sector, natural gas infrastructure must be decommissioned or repurposed, and households must be methodically converted to electric heating and cooking (Stewart 2021).

There has been an enormous amount of scholarly and public attention paid recently to the need to loosen government permitting processes to ensure that they do not hold back the energy transition (Department for Environment 2025; Klein and Thompson 2025). But considerably less attention has been paid to the need for more government oversight, not less, to synchronize both macro- and micro-scale energy investments in ways that enable a smooth and fair transition.

The Macro-Scale: Building Coordinated Networks

The electricity system relies on an almost-perfect balance between supply and demand at all times to function. Managing this calibrated system through the energy transition presents challenges, as renewable energy generation varies more across time and weather conditions than its fossil fuel counterparts (Stewart 2021).

These challenges are manageable but require system planners to develop strategies for running the grid more flexibly, so as to incorporate renewables without sacrificing reliability. A partial solution will be to ensure that sufficient gas remains in the system as a backup for as long as it is needed, but no longer, and that it is not dispatched more often than absolutely necessary. It is unlikely that market signals alone can deliver this careful coordination in resource dispatch (Boyd 2024).2

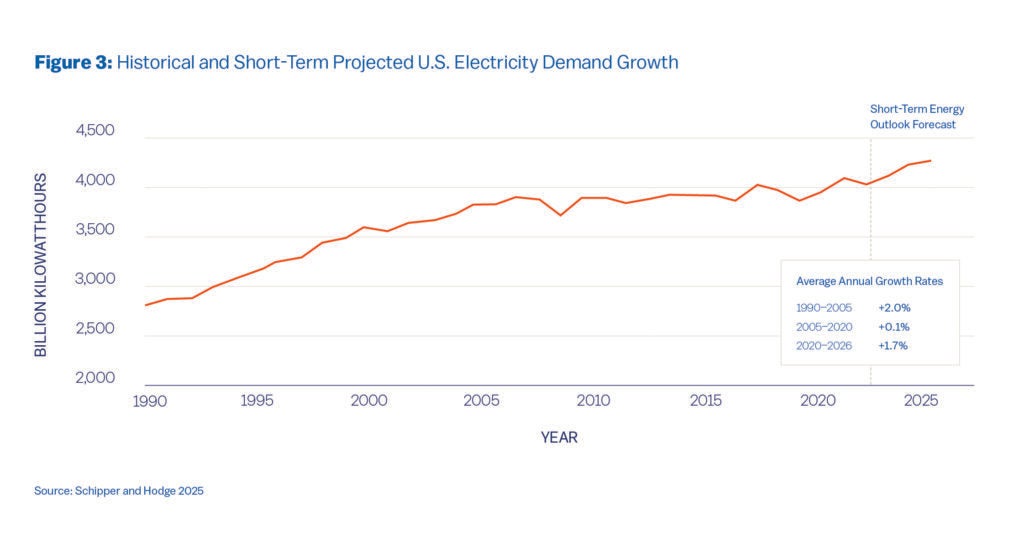

Not only will the grid need to be managed for a changing energy supply, it also must be substantially expanded to meet rising electricity demand from heating and transportation electrification and the rapid rise of energy-hungry artificial intelligence data centers. Electricity demand is already rising substantially (see Figure 3) and is projected to grow by as much as 3.5% data centers per year through 2040, nearly doubling the demands on the grid (Barth et al. 2025).

If new demand is met with fossil fuel resources that cannot be run for their useful life while meeting decarbonization targets, this will add to the cost of the energy transition. For new demand to be met instead by renewable resources will require a targeted buildout of transmission infrastructure.

The Micro-Scale: Empowering Households and Communities

Rapidly achieving a clean energy transition will also require significantly more reliance on small-scale, distributed energy resources and agglomerated actions by households across the energy system—all of which again will require better systems planning and control. Successfully phasing out gas will depend on methodically transitioning households away from old energy sources at the time of appliance and vehicle failures (Willis et al. 2019).

Demand flexibility is one of the most cost-effective ways to balance renewable energy’s variability, but requires system operators to understand the resource potential and its reliability (Chantzis et al. 2023). Similarly, strategically placed rooftop solar, acting in concert with other resources, including storage, can function as a “virtual power plant” that reduces the need for as much large-scale generation and transmission development (Brown 2023, 7). Deploying these promising strategies requires a plan that projects forward coherently across systems, space, and scale.

Planning and Justice

Another acute risk of an unplanned transition is that it may cost significantly more money, should resources be over-built or sited inappropriately at locations that the system cannot support. These risks have substantial justice implications. For one, environmental justice communities often bear the brunt of infrastructure development, such that overbuilt infrastructure is disproportionately likely to harm these communities (Baker 2021).

Moreover, because energy infrastructure is mostly funded through energy bills, energy transition costs are currently recovered mostly in a regressive fashion that requires poorer households to pay a larger percentage of their income (Mastropietro 2019). And without careful planning and cost recovery reforms, as households transition away from the gas system, those left on that system who cannot afford to switch may end up shouldering ever-higher costs. To the extent that good energy system planning helps mitigate costs and eliminate unwise investments, it can also be a vehicle for advancing energy justice.

Toward Whole-System Energy Planning in the U.K.

Among countries working to transition their energy system, one country stands out for recognizing the importance of energy system planning and taking policy steps to improve it: the U.K. Understanding the U.K.’s reforms is particularly useful in the U.S. context because their systems run similarly, since both countries pursued significant restructuring of the industry towards competition and markets in the 1990s (Grubb and Newbery 2018; Lockwood et al. 2022; Spence 2008). Both systems now rely largely on electricity and gas markets to set prices and determine their resource mix.

Unlike the U.S., the U.K. has a legally binding climate change target to reach 100% decarbonization by 2050 (U.K. Parliament 2019). To date, U.K. policy has been extremely effective in achieving progress toward this goal: the country has reduced its emissions to below half of 1990 levels (see Figure 1, supra), largely through policies that mandate certain levels of renewables purchasing and help stabilize renewable energy investments (NESO n.d.).

However, as the U.K. has moved further into the mid-transition phase, there have been mounting concerns that its market-forward frameworks for energy provisioning will not adequately drive a successful energy transition, leading to a search for new institutional forms that culminated in the creation of NESO (Chivukula 2025).

The Road to NESO

As of the early 2010s, the private company National Grid owned most of the U.K. transmission grid and gas pipeline system. National Grid also acted as the “system operator” for the entire transmission grid, in charge of ensuring a balance between electricity supply and demand (Baddeley 2014). In this role, its decisions had “significant impacts on consumers” and the ability to “influence government policy” via its future system forecasts (Baddeley 2014). A separate arm of National Grid performed similar roles for the gas system.

Around 2014, as the U.K. progressed in achieving its decarbonization targets, concerns mounted that the country lacked adequate institutions for proactively managing the changing energy system. Calls grew for someone to take control as an “overall system architect” that could craft long-term plans for achieving decarbonization effectively, affordably, and fairly (Taylor 2014; Taylor and Walker n.d.).

Responding to these concerns, in 2015, the U.K.’s main energy regulator, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), recommended a more robust role for the system operator, which would involve identifying long-term system needs and options to meet these needs. However, recognizing that a private company’s role as a system planner could create possible bias and conflicts of interest, Ofgem also recommended separation between National Grid’s business activities and its planning activities (Baddeley 2014). These suggestions led to 2019 reforms that required National Grid to separate its electricity system operator function, financially and operationally, from its commercial arm (Taylor and Walker n.d.).

For many, these reforms proved too tepid, given that the system operator still resided within National Grid. Policy groups emphasized the importance of ensuring that the entity charged with system planning “be immune from commercial and political pressures given that these investment decisions will create winners and losers” (Taylor and Walker, n.d.).

With National Grid still in control of the system operator, there was a perception that it might give regulatory advice that advanced its affiliated interests as a transmission owner. Moreover, such biased recommendations might be difficult to police because of severe information asymmetries, given the system operator’s unique access to system data and expertise (Stewart 2021).

Ofgem therefore concluded that two additional shifts were needed in U.K. energy system planning: (1) the system operator needed to integrate the planning of electricity, gas, and emerging technologies; and (2) the system operator had to be “free from actual or perceived conflicts of interest” within the energy industry, as well as “free from day-to-day operational control from government” (Ofgem 2022).

To achieve these aims, the government recommended establishing a new, independent public corporation to serve “as a trusted and independent voice within the energy sector” (Ofgem 2022). Notably, although the U.K. considered establishing an energy planning body separate from the system operator, it rejected this option because of “the importance of real-time system balancing experience for effective system planning” (Stewart 2021, 40).

The Energy Act of 2023 instantiated these recommendations into law. The Act created what is now called the National Energy System Operator (NESO), responsible for coordinating electricity transmission and “carrying out strategic planning and forecasting” of both the electric transmission and gas pipeline systems (Energy Act 2023 § 161).

As compared to its predecessor, NESO has four key features that stand out:

- It is publicly owned and independent, free from perceptions that it might be serving commercial rather than public interests.

- It can take a “whole system perspective,” planning both the electricity and gas systems simultaneously (Energy Act 2023, 161)

- In addition to being charged with promoting security of supply and efficiency, it has an explicit net-zero mandate (Department for Energy Security and Net Zero 2023).

- It functions as an independent government corporation with a key advisory role within government, retaining its own voice while providing advice to other energy regulators about how energy system planning should inform their regulatory and policy decisions (Department for Energy Security and Net Zero 2023).

Politically, the U.K. government’s decision to make energy system planning and operations public and independent received broad support, including from the energy industry and from consumer groups (Ofgem 2022). The initiative also proved popular across political parties, championed by the Conservative Party then in power but fully supported by others, including the Labour Party, which came to power in 2024 and has worked to advance NESO’s implementation.

This broad-based support likely stemmed in large part from extreme gas shortages and price spikes experienced in the U.K. in the early 2020s after Russia invaded Ukraine (U.K. Parliament 2025, at 181-82, remarks of MP Bowie). These volatilities—and their painful impacts on U.K. families’ wellbeing—drove home the importance of high-quality, long-term planning.

NESO in Early Action

To set up NESO, the U.K. government purchased the necessary assets for running the organization from National Grid for £630 million in September 2024 and hired the previous National Grid system operator staff, including the CEO (Ambrose 2024a; Chivukula 2025).

One of NESO’s first actions was to produce a report commissioned by the incoming Labour Energy Secretary. This report, Clean Power 2030, advised the government on how the U.K. could meet the Labour government’s accelerated goal of 95% clean electricity by 2030. Although it found the goal technologically feasible, it concluded that achieving it would require “a once-in-a-generation shift in approach and in the pace of delivery,” including significantly speeding the pace of transmission infrastructure development and reforming connection rules and electricity market design (Chivukula 2025, 3).

To enable these reforms, the U.K., Scottish, and Welsh governments commissioned NESO in 2024 to develop the first-ever Strategic Spatial Energy Plan for the UK system. This plan, currently underway, is intended to “be a comprehensive blueprint for the energy system, land and sea, across Great Britain” (Martin et al. 2024).

The first plan will focus specifically on electricity generation, storage, and hydrogen, and is intended to assess “optimal locations, quantities, and types of energy infrastructure required” to meet the U.K.’s clean energy goals (Martin et al. 2024). This assessment will, in turn, feed into more localized energy plans, decisions about energy market reforms, and transmission infrastructure planning.

In speaking with energy sector experts in the U.K. about NESO, a few concerns emerged around administration.3 One interviewee observed that it is not yet clear how NESO’s energy plans will factor into government decisions around energy reforms. Another worried that the bureaucratic space around energy decision-making is becoming increasingly crowded in ways that could impede success.

A third interviewee emphasized that although NESO has been made an independent public corporation, it will need to cultivate a transparent and dialogue-based relationship with the energy industry to maximize its effectiveness. Nevertheless, interviewees were overwhelmingly positive in their assessments that NESO was a step in the right direction that, if implemented well, would help accelerate the U.K.’s transition to clean energy.

Planning for Planning: Distilling the Lessons

It is well-documented that the U.S. suffers from fragmented energy system planning, with responsibilities split across state and federal governments and across institutional actors (Klass et al. 2022). Moreover, the primary actors charged with planning the U.S. electricity grid are “regional transmission organizations.” These organizations have substantial perceptions of bias when it comes to system planning, given that they must appease a voting membership of energy industry insiders (Peskoe 2021; Walters and Kleit 2022; Welton 2021). On the gas side, federal regulators engage in project-by-project approval with no overall system planning and rarely deny gas pipeline applications (Gocke 2023).

Thus, the precise concerns that motivated U.K. planning reforms—fragmentation and concerns over potential bias—are prevalent in the U.S. system. Could a similar set of reforms be the answer to our planning challenges?

Politically and legally, implementing the NESO model in the U.S. would present some additional complexities due to our decentralized structure for energy system planning. U.S. law reserves control over energy generation and supply decisions to the states, while giving the federal government control over interstate electricity transmission and gas pipelines.

While this framework would make a full-scale NESO model practically and politically challenging, it also creates space for creativity and experimentation with similar structures. The current federal administration is unlikely to pursue energy system planning reform, focused as it is on downsizing government and eliminating climate initiatives. But a future, forward-looking administration should seriously consider the creation of a new, independent federal energy system planning authority or regional planning authorities modeled on NESO.

Such authorities should be given joint power over the planning of electricity transmission and gas pipeline systems and a decarbonization mandate that allows them to prioritize clean energy solutions (Macey and van Emmerick 2025; Welton 2024). In this respect, NESO’s four core features offer a blueprint for designing an effective whole-of-system planning effort.

Moreover, U.S. states pursuing the energy transition within a federal policy vacuum could also draw valuable lessons from the U.K.’s planning innovations. Leading states are struggling with many of the same questions facing U.K. energy system planners, including how to implement a coordinated gas system wind-down and rationalize clean energy siting (Rackerby 2024; Shemkus 2024). NESO offers a promising model for state-level experiments in spatial and combined resource planning that could help these states prove themselves valuable pioneers in completing the energy transition.

Shelley Welton

Presidential Distinguished ProfessorShelley Welton is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Law and Energy Policy with the Kleinman Center and Penn Carey Law. Her research focuses on how climate change is transforming energy and environmental law and governance.

Ambrose, J. 2024a. “U.K. Government to Buy Electricity System Operator from National Grid for £630m.” The Guardian, September 13, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/sep/13/uk-government-to-buy-electricity-system-operator-from-national-grid-for-630m

Abrose, J. 2024b. “The End of an Era: Britain’s Last Coal-Fired Power Plant Shuts Down.” The Guardian, October 5, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/sep/30/end-of-an-era-as-britains-last-coal-fired-power-plant-shuts-down

Baddeley, J. 2014. “Integrated Transmission Planning and Regulation (ITPR) project: Draft Conclusions.” Ofgem.

Baker, S. 2021. Revolutionary Power An Activist’s Guide to the Energy Transition. https://islandpress.org/books/revolutionary-power

Barth, Adam, Humayun Tai, and Ksenia Kaladiouk. 2025. Powering a New Era of U.S. Energy Demand. McKinsey & Co., April 29, 2025. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/america-at-250

Boyd, W. 2024. “Decommodifying Electricity.” Southern California Law Review, 97:101. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4889020

Brown, K. 2023. “Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) Could Save US Utilities $15-$35 Billion in Capacity Investment Over 10 Years.” Brattle. April 2, 2023. https://www.brattle.com/insights-events/publications/real-reliability-the-value-of-virtual-power/

Chantzis, G., Giama, E., Nižetić, S., and Papadopoulos, A. M. 2023. “The Potential of Demand Response as a Tool for Decarbonization in the Energy Transition.” Energy and Buildings 296: 113255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113255

Chivukula, S. 2025. February 5. National Energy System Operator (NESO). Institute for Government. February 5, 2025. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/national-energy-system-operator

Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. 2023. Future System Operator: Second Policy Consultation and Project Update. GOV.UK.

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Environment Agency, Welsh Government, Natural Resources Wales, and E. Hardy, MP. 2025. Environmental Permit Reforms to Empower Regulators to Slash Business Red Tape. GOV.UK. April 8 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/environmental-permit-reforms-to-empower-regulators-to-slash-business-red-tape

United Kingdom. 2023. Energy Act 2023. Independent System Operator and Planner.

European Commission. n.d. EDGAR: The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research—Country Profile U.K. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/country_profile/GBR

European Commission. n.d. EDGAR: The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research—Country Profile U.S.A. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/country_profile/USA

Gocke, A. 2023. “Pipelines and Politics.” Harvard Environmental Law Revenue 47: 207.

Gocke, A. Forthcoming. “The Law Of The Mid-Transition.” Michigan Law Review. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5387156

Grubb, M., and Newbery, D. 2018. “UK Electricity Market Reform and the Energy Transition: Emerging Lessons.” The Energy Journal 39 (6,): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.39.6.mgru

Grubert, E., and Hastings-Simon, S. 2022. “Designing the Mid-Transition: A review of Medium-Term Challenges for Coordinated Decarbonization in the United States.” WIREs Climate Change, 13 (3): e768. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.768

IEA. 2024. Global EV Outlook 2024. International Energy Agency (IEA). https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars

Klass, A., Welton, S., Macey, J., and Wiseman, H. 2022. “Grid Reliability Through Clean Energy.” Stanford Law Review 74: 969.

Klein, E. and Thompson, D. 2025. Abundance. Simon & Schuster.

Knodt, M., and Kemmerzell, J. eds. 2022. Handbook of Energy Governance in Europe. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43250-8

Labour Party. n.d. Make Britain a Clean Energy Superpower. https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Make-Britain-a-Clean-Energy-Superpower.pdf

Macey, J., and van Emmerick, E. 2025. “Towards a National Transmission Planning Authority.” Harvard Environmental Law Rev 49: 79. https://ssrn.com/abstract=5177554

Martin, Gillian, Michael Shanks, and Evans, R. 2024. Strategic Spatial Energy Plan: Commission to the National Energy System Operator (NESO). Department for Energy Security & Net Zero. October 22, 2024.

Mastropietro, P. 2019. “Who Should Pay to Support Renewable Electricity? Exploring Regressive Impacts, Energy Poverty and Tariff Equity.” Energy Research & Social Science 56: 101222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101222

National Energy System Operator. n.d. Grid Code (GC). https://www.neso.energy/industry-information/codes/grid-code-gc

National Energy System Operator. n.d. NESO Clean Power 2030. Retrieved August 21, 2025. https://www.neso.energy/document/346651/download

Ofgem. 2022. Future System Operator: Government and Ofgem’s Response to Consultation. Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy.

Peskoe, A. 2021. “Is the Utility Transmission Syndicate Forever” Energy Law Journal 42:1. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3770740

Rackerby, S. C. R., Jenna. 2024. “Delays in Renewable Energy Siting in New York: A Closer Look at State Audit Findings.” E2 Law Blog. May 8, 2024. https://www.gtlaw-environmentalandenergy.com/2024/05/articles/state-local/new-york/delays-in-renewable-energy-siting-in-new-york-a-closer-look-at-state-audit-findings/

Schipper, M., and Hodge, T. 2025. “After More Than a Decade of Little Change, U.S. Electricity Consumption is Rising Again.” U.S. Energy Information Administration. May 13,2025. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=65264

Shemkus, S. 2024. “More Questions Than Answers After Massachusetts Order to Transition from Natural Gas.” Canary Media. February 5, 2024. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/enn/more-questions-than-answers-after-massachusetts-order-to-transition-from-natural-gas

Sivani, Chivikula. 2025. “National Energy System Operator (NESO).” Institute for Government. February 5, 2025. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/national-energy-system-operator

Spence, D. 2008. “Can Law Manage Competitive Energy Markets.” Cornell Law Review: 93 (4): 765.

Stewart, H. 2021. “Review of GB Energy System Operation.” Ofgem.

Taylor, P. 2014. We Need an Independent Architect to Redesign the U.K. Energy Industry,” The Guardian. June 2, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/big-energy-debate/energy-industry-independent-market-architect-redesign

Taylor, P., and Walker, S. n.d. “The Role of the System Architect.” National Centre for Energy System Integration.

The White House. 2024. Fact Sheet: President Biden Sets 2035 Climate Target Aimed at Creating Good-Paying Union Jobs, Reducing Costs for All Americans, and Securing U.S. Leadership in the Clean Energy Economy of the Future. Dec. 19, 2024. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/12/19/fact-sheet-president-biden-sets-2035-climate-target-aimed-at-creating-good-paying-union-jobs-reducing-costs-for-all-americans-and-securing-u-s-leadership-in-the-clean-energy-economy-of-the-future/

U.K. Parliament. 2019. The Climate Change Act 2008 (2050 Target Amendment) Order 2019. King’s Printer of Acts of Parliament. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2019/9780111187654

U.K. Parliament. 2025. Energy Bill [HL]—Hansard—UK Parliament. August 21, 2025. https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2023-09-12/debates/3294294B-3911-484C-A3A3-3CA908ADBF26/EnergyBill(HL)

Uniyal, A. 2024. “Overcoming Grid Inertia Challenges in the Era of Renewable Energy.” Energy Central. August 14, 2024. https://www.energycentral.com/energy-management/post/overcoming-grid-inertia-challenges-era-renewable-energy-wHjW7B8HN8Rt550

Walters, D. E., and Kleit, A. N. 2022. “Grid Governance in the Energy Trilemma Era: Remedying the Democracy Deficit.” Alabama Law Review 74:1033. https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1792

Welton, S. 2021. “Rethinking Grid Governance for the Climate Change Era.” California Law Review 109: 209. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/2848

Welton, S. 2024. Governing the Grid for the Future: The Case for a Federal Grid Planning Authority. The Hamilton Project. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/policy-proposal/governing-the-grid-federal-grid-planning-authority/

Willis, R., Mitchell, C., Hoggett, R., Britton, J., and Poulter, H. 2019. Enabling the Transformation of the Energy System: Recommendations from IGov. IGov.

- Indeed, the U.K. retired its last coal-fired power station in 2024 (Ambrose 2024b). [↩]

- Renewable energy also requires different strategies for managing short-term fluctuations in frequency, given its different resource characteristics. Grid codes have long helped to deal with these requirements and will become increasingly important to manage unwanted instabilities (National Energy System Operator n.d.; Uniyal 2024). [↩]

- This paragraph draws from eight confidential interviews conducted by the author in spring and summer 2025 with U.K. energy sector experts that held roles across industry, policy advocacy, government, and academia. [↩]