Philanthropic Partnerships Towards Combating Energy Poverty

Energy poverty receives less funding by foundations compared to other forms of poverty. Despite this, partnerships with other agencies can point to innovative solutions to combat energy poverty.

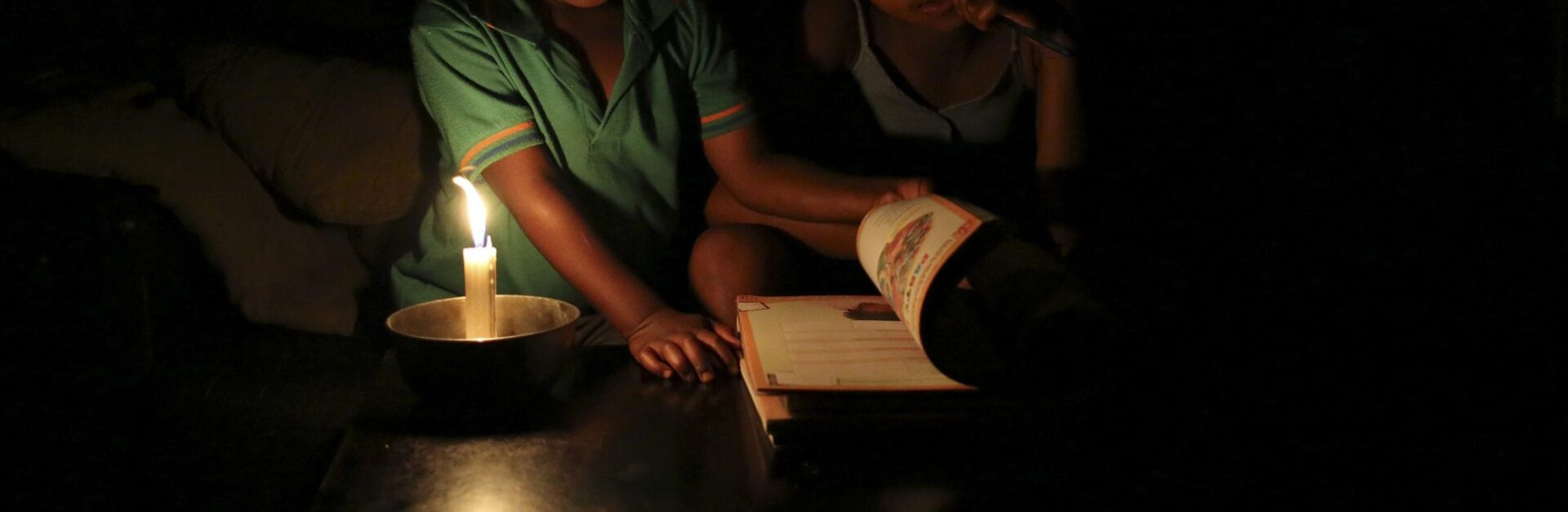

Global energy poverty sees marginal grantmaking compared to economic poverty more generally. According to Candid’s grants database, giving towards “poverty” in the last decade yields nearly $3 billion, while “energy poverty” grants in the same timespan totaled $46 million—roughly 1.5% of the broader issue. The sentiments of social impact strategists Rachel Pritzker and Mike Berkowitz from nearly six years ago remain—despite energy’s role in improving health (to help run hospitals), education (to close the digital divide), gender equality (to make labor more efficient), and poverty itself (to catalyze economic development), philanthropies have given little attention to the subject.

Five years ago, Bill Gates blogged about how energy poverty has affected lives around the world, stressing that delivering “cleaner, cheaper energy to the developing world” can lead to better outcomes for children. However, the Gates Foundation has offered no grants to support work specifically on energy poverty.

It is worth recognizing that the topic has great value for philanthropies. Studies have shown energy access’ positive spillover effects toward economic development and energy poverty’s negative effects on the health of entire regions, showcasing its global implications. Philanthropy clearly has a role to play in fighting energy poverty, but philanthropists have, by and large, not yet answered the call. Fortunately, the Rockefeller Foundation has provided a model for addressing energy poverty. Their program has been defined largely by partnerships spanning educational institutions, multinational companies, and regional governments.

The Rockefeller Foundation is one grant-issuing organization that stands out in the strides it has made to recognize and act upon the global energy poverty problem. Its work is divided into knowledge-building and energy finance support. In 2019, Rockefeller began The Global Commission to End Energy Poverty (GCEEP) led by officials from development banks, businesses, and research institutions. The GCEEP partners with MIT to develop working papers and reports on energy access. At the end of 2020, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) committed $2 billion in renewable energy investments, with $50 million of de-risk from Rockefeller, and a “multi-partner global platform” distributing renewable energy to developing countries. DFC estimates that the investment could reach 800 million people—the amount of people across the globe without electricity.

Rockefeller has also engaged in place-based efforts regarding energy poverty. Smart Power India (SPI) was created in 2015 to initially provide microgrids in the state of Uttar Pradesh, envisioning energy access as the key to economic opportunity. Operating under Rockefeller’s support, SPI reached across sectors to scale this mission. For example, the Model Distribution Zone Program has led to increased capacity to distribute electricity to the state of Odisha in collaboration with their public electricity supply agency. In the private sector, SPI has facilitated the creation of TP Renewable Microgrid Ltd., operated under Tata Power. Their goal is to supply 10,000 villages with electricity by 2026. A recent accomplishment was creating a biogas plant in Bihar that runs on local cow dung.

While Rockefeller’s work is commendable, the philanthropic sector’s response as a whole remains weak. Rockefeller is the only global foundation explicitly addressing the energy poverty crisis. Scaling down this partnership-based approach could help to catalyze more widespread engagement. This may be advantageous for smaller foundations, as equitable collaboration with energy-starved communities can empower citizens and allow for clearer energy poverty-related goals. Foundations at smaller levels have a more cohesive knowledge of the stakeholders in a certain region, and like the case of Rockefeller and India, can lead to targeted and consistent impacts. This is rooted in multi-sector partnerships, from the local government to the utility companies.

Foundations could innovate with place-based renewable energy access investments and build localized coalitions to put an end to global energy poverty, but they cannot do this alone.

This insight is a part of our Undergraduate Seminar Fellows’ Student Blog Series. Read work from other students and learn more about the Undergraduate Climate and Energy Seminar.

Adam Goudjil

Student Advisory Council MemberAdam Goudjil is a Kleinman Center Student Advisory Council Member and an undergraduate student studying urban studies at the College of Arts and Sciences. Goudjil was also a 2021 Undergraduate Student Fellow.