Fanning the Flames: Mismanagement and California’s Wildfires

Exacerbated by climate change, the delivery of electricity has become a significant wildfire risk in recent years. Despite the cost, policies like burying power lines have been shown as an effective way to curtail fires.

California experienced large and dangerous wildfires in 2019. The most recent ones made headlines for damaging Sonoma and Napa County’s wine country. There were also significant fire events in Southern California, which threatened the city of Los Angeles and its surrounding areas. According to a recent Vox article, the state has had 5 of its 10 largest, and 7 of its 10 most destructive wildfires ever in the last decade. Over the last several weeks, during the height of the southern hemisphere’s summer, the world has watched as Australia has tackled even more severe and widespread brush fires.

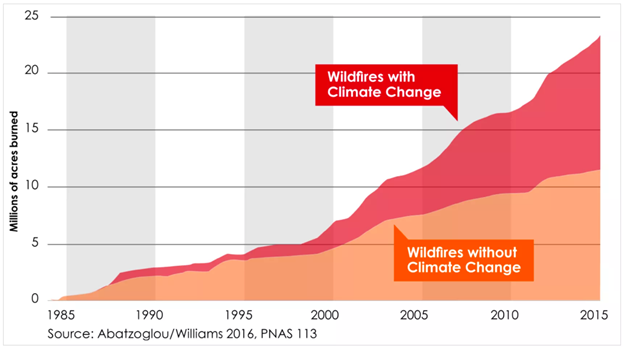

As demonstrated by figure 1, the global increase in severity of wildfires is highly linked to climate change.

A study published this October in the AGU 100 (first published in the Journal of Earth and Space Science) contests that the increase in burned acreage in California is a result of the drying of brush and other kindling due to a changing local climate. A regional analysis showed that an increase in these conditions can be especially well observed in the traditionally wetter regions of Northern California. The paper also says the ability of this dry biomass to feed large fires is non-linear, leading to an exponential growth in the size and area burned.

Researchers found that warm season vapor-pressure deficit (a measure of humidity vs. aridity) and daily maximum temperature were the most predictive factors in determining the fire risk. Both of these conditions are driven by climate change, and contributed to 2018 being the worst year on record for area burned by California wildfires.

Other human factors contributing to fires are logging, housing development, and power infrastructure. The size of wildfires is exacerbated by unsustainable logging practices, such as clear-cutting and patterned replanting, which have been relied upon since the 1990’s. California has rampant suburban sprawl due to the high cost of urban housing, and many structures now inhabit wooded areas. Future development in these areas should be limited and concentrated in lower risk regions.

Moreover, the delivery of electricity to suburban and rural Californians has become a significant wildfire risk in recent years as evidenced by the recent situation involving PG&E, the largest utility in Northern California. The company was forced into bankruptcy in January 2019 because courts ruled that its poorly maintained field equipment was responsible for igniting the Camp Fire, which killed 85 people and destroyed the town of Paradise, CA.

Thousands of miles of PG&E’s distribution lines weave through sparsely populated and heavily wooded areas of the state that are susceptible to wildfires. There are limited remaining options except for the state to provide financial and management interventions in order to improve this aging infrastructure. This maintenance could be achieved through a tax, a tariff on electricity, or a federally appointed arbitrator taking charge of PG&E during its bankruptcy and carefully monitoring how it distributes its funds. Moreover, the state’s park rangers and firefighters could work in the cooler months to clear out dry brush, to re-incorporate fire prevention into state policy.

Australia’s situation is a good analog for California, as nearly 80% of wildfire related deaths in Australia have come as a result of fires started by power lines. Burying these power lines has been shown as an effective policy to curtail fires despite the higher cost per mile of lines. Some of these changes, if enacted with smart climate legislation, could reduce the severity of future fires in California, and around the world.

Giridhar Sankar

Wharton SchoolGiridhar Sankar is currently pursuing a master’s of business administration from the Wharton School and a master’s of international studies from the Lauder Institute.