A More Cost-Effective Approach to Encourage Energy Conservation

Energy conservation is viewed as a key pillar of climate change mitigation, but the impacts of past residential energy efficiency programs are hotly contested. Optimizing the design of these nudges can yield significant results.

A vast literature of prior work in program evaluation focuses on identifying policies that have beneficial impacts. The gold standard for program evaluation is randomized control trials, which allow researchers to understand the causal effects of economic interventions without relying on strong assumptions.

The 2019 Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to three economists for pioneering the application of field experiments in economics. Recent methodological and computational advances present promising new opportunities to optimize the design of programs through targeted interventions after initial experiments.

We use a recently developed method, in combination with data from a field experiment, to study whether it is feasible to improve the design of a common energy conservation program in order to reap greater energy and cost savings. The specific program we study is Home Energy Reports, a large-scale behavioral intervention to encourage energy conservation. Our study looks at data from the Northeastern United States.

Under this program, a utility mailed personalized letters to randomly assigned households with feedback and social comparisons on energy consumption to “nudge” households to change their daily energy use habits and potentially invest in energy-efficient appliances. Our research goal is to identify the households that responded most favorably to these letters, and to assess the potential gains from an approach that only sends letters to these households.

There are two reasons why it may be worthwhile to selectively target certain households instead of sending letters to all utility customers. First, it has been documented that some households could increase electricity consumption after receiving positive feedback that they use less energy relative to neighbors. Second, program implementation costs are not negligible—in fact it would cost over 1 billion dollars every year if a comprehensive program were adopted nationally.

Therefore, it may be beneficial to use information from prior experiments to identify and target households that respond most favorably to the letters based on observable demographic characteristics. This could improve both the effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of the program.

We use a statistical policy learning method called empirical welfare maximization to determine which households to send letters to. This approach uses simple rules to classify households as recipients or non-recipients. The use of simple rules is motivated by the following factors:

- Baseline energy consumption is a key predictor in households’ responses to home energy reports in the program (which is confirmed both in our dataset and in prior studies).

- Simple treatment rules are transparent and easy to implement in practice.

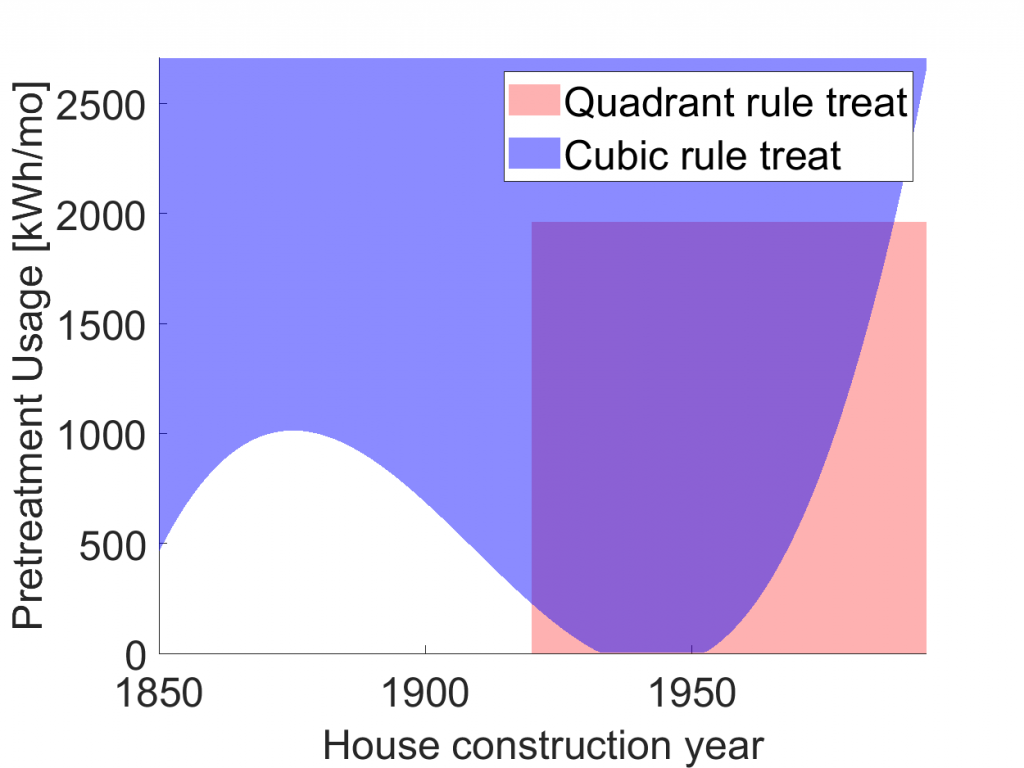

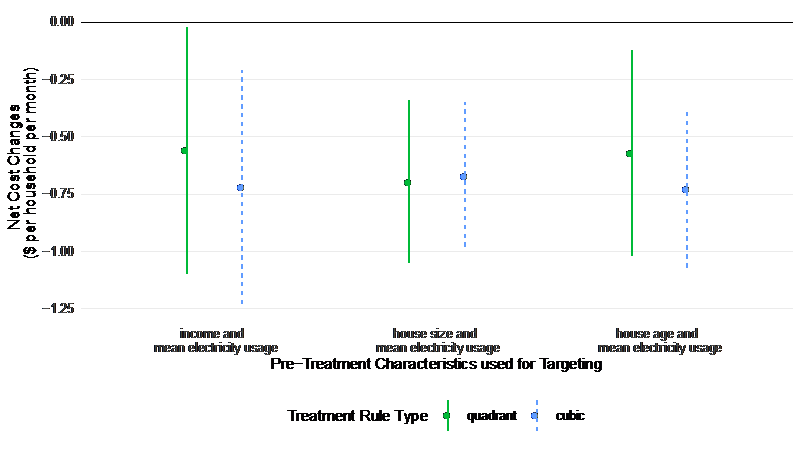

Therefore, we search for treatment rules using two characteristics at a time (baseline consumption and household income, house size, or house vintage) to identify the group that, when targeted, maximizes expected benefits.

With our targeted treatment assignment, we find large gains in the program’s cost-effectiveness: roughly $385,000 to $485,000 in total net cost reductions per year for the sample.1 If scaled to the entire state, the annual net cost reductions could reach at least $3 million. The predicted reduction in electricity consumption from selective targeting roughly doubles the consumption reduction of the original program’s randomized approach.

The use of statistical treatment rules is receiving growing attention in economics, medicine, and many other disciplines. Our findings underscore the practical value of these methods and their potential to generate significant benefits in many domains.

This post highlights research presented at the Northeast Workshop on Energy Policy and Environmental Economics, hosted this year at the University of Pennsylvania.

Todd Gerarden

Assistant Professor, Cornell UniversityTodd Gerarden is an assistant professor in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University. He conducts research in environmental and energy economics.

Muxi Yang

Doctoral Student, Cornell UniversityMuxi Yang is a Ph.D. candidate in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University. Her research interests include energy economics and urban and transportation economics.

- Net total cost reduction refers to the sum of households’ cost savings and the program implementation cost. From the program designer’s perspective, both the cost savings from reduced energy consumption and the implementation cost of program to achieve these cost savings are important metrics to take into account. [↩]