Tracking Gasoline Price Impacts in California: Part 2

A new controversy over refiners’ apparent decision to pass along higher costs to California drivers in January, not July, demonstrates that the Low Carbon Fuel Standard has a direct and predictable effect on retail gasoline prices.

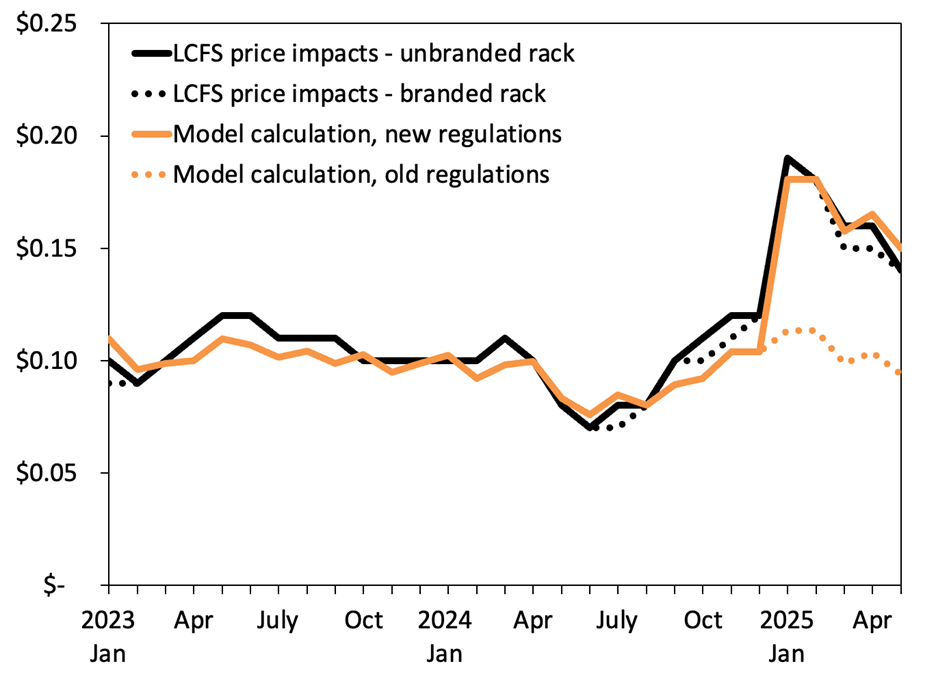

In an earlier post, I reviewed public data from oil refiners about the per-gallon cost of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) they pass along to consumers in the form of higher gasoline prices at the pump.

Because these data show a modest increase in retail gasoline prices, rather than a dramatic spike, some have claimed that program costs will stay low. But it’s a fallacy to assume that the future will look like the past, and in this case, the evidence indicates the opposite: that costs are likely to rise substantially over time.

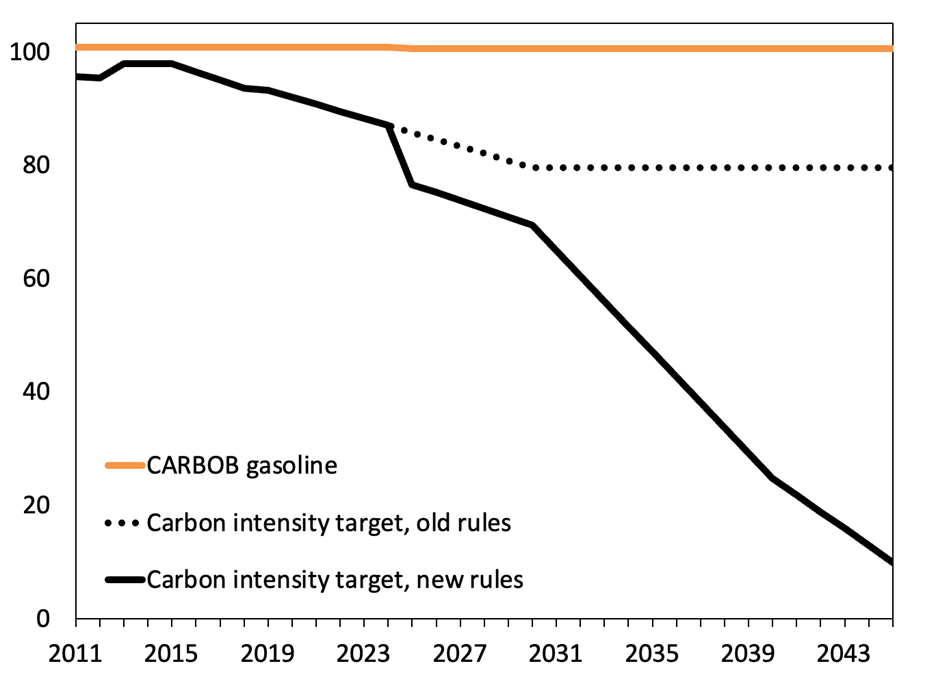

The primary reason that reported fuel price impacts grew only modestly is that LCFS credit prices declined in parallel. This effect masked the impact of the growing ambition of the LCFS program, which requires fuel sellers to meet carbon intensity targets that decline each year (see Figure 1).

A new controversy over California gasoline prices demonstrates these dynamics. As Politico reports, refiners appear to have been passing along higher costs associated with the LCFS program’s 2025 carbon intensity targets beginning in January 2025—despite the new rules having an effective date of July 1, 2025.

Beyond raising concerns about refiners’ practices, the state’s top climate regulator also claimed victory in the broader gasoline pricing debate:

“It does sort of validate the points that we were making over time,” said California Air Resources Board Chair Liane Randolph. “The pricing has played out in pretty much the way we anticipated.”

In fact, this episode directly contradicts the climate regulator’s position that the LCFS program is not “driving up the cost of gasoline” and that there is “no direct relationship between LCFS credit prices and retail gasoline prices.”

Using historical LCFS credit prices, it is possible to accurately reproduce the gasoline price impacts refiners report to the California Energy Commission (see Figure 2).

These calculations suggest that the lower LCFS carbon intensity target for 2025 caused a significant retail price impact in January, even if refiners shouldn’t have started passing those costs on to consumers until July.

That’s bad news for future gasoline price impacts for two reasons. First, program carbon intensity targets are scheduled to decline going forward (see Figure 1). Second, LCFS credit prices can’t get much lower and are likely to rise over time; market rules allow them to more than quintuple.

A few caveats are in order. One is that fuel price impacts are self-reported by refiners, who might be saying one thing and doing another. A second is that public data are reported as monthly averages across firms and with few significant digits, while real-world data are more granular, proprietary, and likely vary by firm.

None of that changes the basic economics of the LCFS program. By requiring increasingly stringent carbon intensity reductions from fossil fuel sellers, the program imposes higher costs over time.

As someone who supports ambitious climate policy, I don’t object to programs with price tags. But it’s important to be honest, particularly when the climate regulator is asking drivers to pay billions for biofuels that may emit more than the fossil fuels they replace.

Danny Cullenward

Senior FellowDanny Cullenward is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center. He is an economist and lawyer focused on the scientific integrity of climate policy with additional appointments at the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal at American University and Google.