Methane Offsets in the Final Hydrogen Production Tax Credit Regulations

Robust safeguards in the final regulations for the Section 45V hydrogen tax credit will avoid the worst-case climate outcomes for methane-based production. Although the rules authorize the use of methane offsets from animal manure to qualify conventional hydrogen production, that use is limited and primarily applies to new hydrogen production facilities.

Last week the Department of the Treasury finalized regulations implementing the hydrogen production tax credit under Section 45V of the tax code. To qualify for the tax credit, a hydrogen producer needs to meet strict greenhouse gas emissions standards using the technical methods established by these regulations.

For this post, we decided to look at how the final rules address the use of alternative methane feedstocks produced from landfills, animal manure, and other waste streams. We chose this focus because alternative methane feedstocks could qualify conventional fossil hydrogen producers for the lucrative 45V tax credit—effectively as methane offsets. (See John Quigley’s post for more about the rule’s broader impacts.)

As two of us wrote for Heatmap News, a fossil hydrogen producer could have earned valuable tax credits if they were allowed to blend just a small percentage of alternative methane feedstocks into a conventional production process. If allowed, this would fully offset producers’ greenhouse gas emissions (similar to what is allowed under California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard) and qualify them for the top tier of the 45V tax credit.

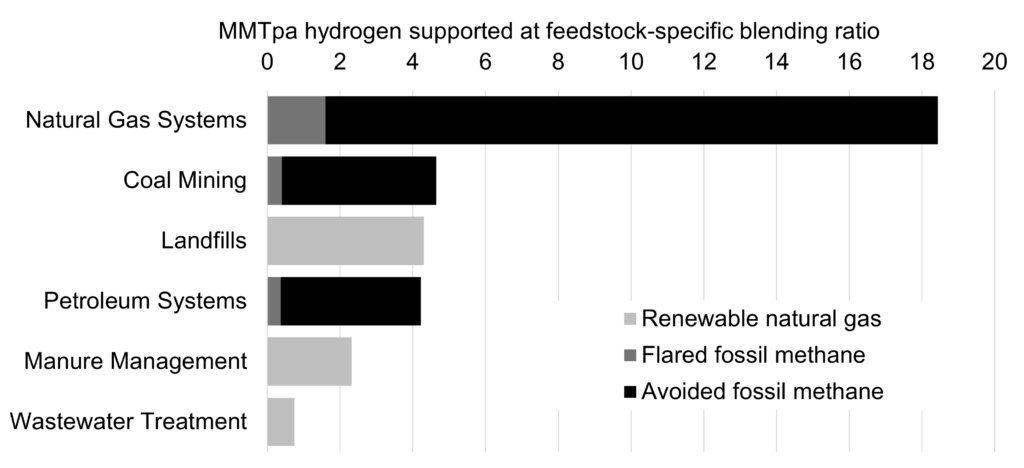

Last summer, the three of us quantified the potential impacts of methane offsetting under the hydrogen production tax credit. Using official emissions data, we calculated the maximum hydrogen production that could be supported with and without blending of alternative methane feedstocks. We shared our initial findings in a public comment letter to the Department of the Treasury, with a peer-reviewed version forthcoming at Environmental Research: Energy.

We found that methane offsets with blending could support up to 35 million tons of conventional hydrogen production a year (see Figure 1)—more than triple the Department of Energy’s 2030 clean hydrogen target. This worst-case outcome would stifle the nascent clean hydrogen industry by subsidizing conventional production processes, increase greenhouse gas emissions by 3 billion tCO2e, and cost taxpayers about $1 trillion.

To avoid these risks, we recommended that treasury:

- Prohibit feedstock blending and treat each feedstock as a separate production process;

- Prohibit the use of negative carbon intensity scores; and

- Require ambitious baseline scenarios for alternative methane feedstocks that assume significant climate action, rather than perpetual methane emissions.

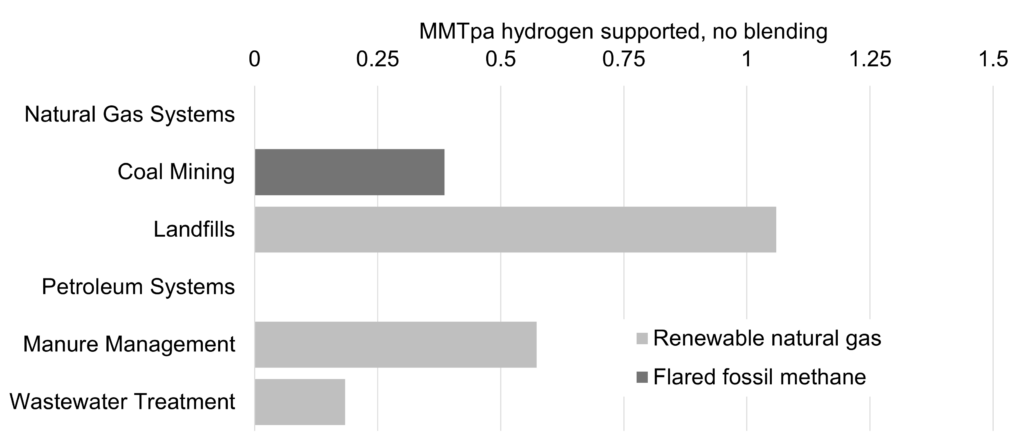

Consistent with our recommendations, the final regulations prohibit feedstock blending and require ambitious baseline scenarios (primarily capture and flaring) for methane sourced from wastewater, landfills, and fossil fuel systems. These safeguards make a big difference. We estimate they reduce the maximum production of subsidy-eligible conventional hydrogen from 35 to about 2 million metric tons per year (see Figure 2)—and likely substantially less, as the baseline requirements may disqualify many wastewater, landfill, and coal mine sources.

Unfortunately, the final regulations assign a negative carbon intensity score of -51 gCO2e/MJ to manure methane. The good news is that this carbon intensity score is about ten times more conservative than California’s Low Carbon Fuels Standard—which features scores as low as -790 gCO2e/MJ—but it still allows conventional hydrogen producers to earn a tax credit simply by purchasing credits for manure-based methane.

In practice, the final rules may limit that risk. Both new and existing production facilities can qualify for the tax credit using alternative methane feedstocks, but only for the first ten years of their operations. Meanwhile, the use of “book-and-claim” methane offsets won’t be allowed until 2027 at the earliest—so existing producers may not be eligible for long, if at all.

While it is possible that investors will rely on lucrative subsidies earned via methane offsets to build new production capacity, the need for permitting and new capital outlays—rather than mere certificate trading—could limit uptake. Nevertheless, there is some risk that the tax credit will encourage new fossil hydrogen production paired with manure-based methane offsets.

Taken as a whole, the final regulations impose substantial safeguards that prevent most conventional fossil hydrogen production from relying on methane offsets to earn the valuable Section 45V tax credit. While some risk remains, that risk is largely limited to the possibility of newly constructed conventional hydrogen production, rather than certificate-trading to subsidize existing production.

Danny Cullenward

Senior FellowDanny Cullenward is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center. He is an economist and lawyer focused on the scientific integrity of climate policy with additional appointments at the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal at American University and Google.

Emily Grubert

Associate Professor, University of Notre DameEmily Grubert is associate professor of sustainable energy policy, and, concurrently, of civil and environmental engineering and earth sciences at the University of Notre Dame. Her research focuses on justice-oriented deep decarbonization and decision support tools for large infrastructure systems.

Wilson Ricks

Postdoctoral Researcher, Princeton UniversityWilson Ricks is a postdoctoral researcher in the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment at Princeton University, where he employs macro-energy systems modeling to assess the role of policies and technologies in electricity systems decarbonization.