Energy Consumption and Cost Burdens in Multi-Family Housing

Low-income households are more likely to be subjected to high energy cost burdens due to inefficient housing, but new energy disclosure data can be used to develop programs that retrofit properties and reduce this inequity.

For some time, we have been talking about the potential that big data holds for addressing issues of global warming and climate justice. My research with Constantine Kontokosta and Bartosz Bonczak shows how we can use publicly disclosed energy use data to develop programs that make our nation’s rental housing stock more efficient and equitable. Such programs are important now more than ever, with rent burdens at unprecedented levels, particularly for the lowest income households, and the negative effects of global warming becoming increasingly clear.

State and local governments across the country are requiring owners of residential and commercial properties to report property-level data on energy use. There are over 20 cities and 10 states with such disclosure laws, and these laws often take on different forms in different places. For example, in Boston and Cambridge multifamily buildings above 50 units are required to disclose their energy usage, whereas in New York and Washington D.C. the requirement applies to buildings above 50,000 square feet. These data have already been used by researchers to look at energy consumption levels, and how building characteristics and affordable housing subsidies affect these consumption levels. In a forthcoming peer-reviewed paper, my colleagues and I use these data in five cities (Boston, Cambridge, New York, Washington D.C., and Seattle) to develop building-level estimates of energy cost burdens by household income level and demographic characteristics, and calculate whether and how energy retrofit investments with short- and long-term payback periods reduce such burdens.

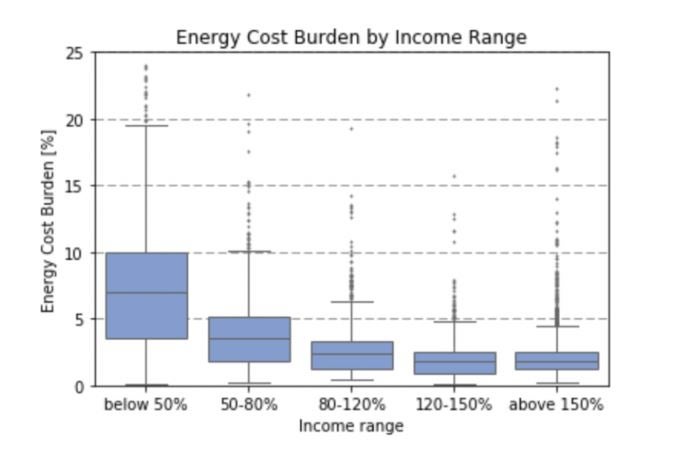

As seen in the figure below, we find that the average household with income below 50 percent of area median income has an energy cost-burden of roughly 7 percent, which is 5 percentage points higher than those households with incomes above 120 percent of area median income. What is more concerning is that the cost burdens for the lowest income households can be as high as 20 percent. These burdens are driven by the inefficiency of the housing that low-income household can afford and access, as opposed to their consumption decisions. This means that a primary way to reduce such burdens is to improve the energy efficiency of the poorest quality rental units in our housing stock.

To explore the feasibility of this solution, we use energy audit reports for approximately 3,000 residential buildings in New York City to estimate the impact of energy retrofits on energy cost burdens. Our models show that, on average, energy retrofits with payback periods of less than two years could result in an annual savings of approximately $112 per household per year, and such savings increase to almost $300 per year and, in some cases, as much as $1,200 per year when looking at improvements with 10 year payback periods. The cost savings are a product of lower energy consumption levels, and thus represent a secondary benefit of reducing the environmental footprint of the existing housing stock.

One of the main contributions of this research is that it shows the importance, and power, of publicly disclosed energy use data, and makes the case for expanding local laws that require property owners to report these data. Second, the methods used in this paper can be replicated by local planners to develop programs that target specific properties for energy retrofits. Further, these data can be combined with those of other programs, like Low Income Housing Assistance Program, to ensure such limited resources go even further. Ultimately, energy cost burdens are an important climate change and climate justice issue, and our research shows how big data can be used to address both.

Vincent Reina

Associate Professor of City and Regional PlanningVincent Reina is an assistant professor of city and regional planning at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design.