Subsea Sabotage: Protecting Energy Infrastructure from Hostile Aggression

Once a niche area of energy security policy, the physical protection of energy and critical infrastructure installations has become a national security requirement due to the growing trend of physical sabotage incidents worldwide. This digest, a companion to the Underwater Mayhem report, is part of a multi-year research project focused on improving monitoring and deterrence to counter the escalating count of subsea critical infrastructure sabotage attacks now ubiquitous around the globe.

At A Glance

Key Challenge

The massive extent and remote maritime domains in which offshore energy and critical infrastructure exist present technical and policy challenges for monitoring and deterring sabotage. Recent subsea attacks by malign actors, like the Russian Federation, require urgent additional policy action.

Policy Insight

NATO member states that have sustained energy infrastructure sabotage in which state actor attribution for the attacks has been made should invoke NATO’s Article 4 consultative mechanism provision. States should also build public-private partnerships to increase commercial geospatial monitoring.

Companion Report

This digest serves as a companion to the report “Underwater Mayhem: Countering Threats to Energy and Critical Infrastructure Across the NATO Alliance and Beyond,” part of a multi-year research project at the University of Pennsylvania.

Download Full Report

Introduction

Even in the earliest moments of the crisis, the magnitude of the events unfolding in the normally quiet waters just miles from his office were evident to the police commissioner of Bornholm, a windswept Danish island in the Western Baltic Sea. “As soon as we learned of the explosions… it was clear from the very beginning that something very extraordinary had taken place.”

That commissioner, Martin Preisz Gravesen of Bornholms Politi, explained that in those immediate hours “the first step was to assess what the danger to lives and property might be, which needed to take place even before the beginning of the investigation for cause.”

While the investigation for cause would go on to grip Europe’s energy and national security circles for years to come, establishing what had taken place in the early hours of September 26, 2022 in the inky waters of the Baltic Sea was front of mind for European authorities.

Based out of Sweden’s historic maritime port of Karlskrona, Mattias Lindholm, spokesperson for the Swedish Coast Guard, illustrated the dramatically increasing stakes. “Swedish Coast Guard responders thought immediately the incident might have involved Nord Stream since they could see a huge bubbling cloud that had formed. The sea was boiling!”

Beyond immediate safety and environmental concerns, the realization that Russia’s dual Nord Stream subsea natural gas pipeline systems might be involved—with blast sites in both Danish and Swedish waters—underscored the growing geopolitical seriousness of the situation since, in Lindholm’s view, “given that Russia was a country of interest related to Nord Stream, the response rapidly went from an environmental issue to a geopolitical and security issue, since it would now have to do with defense as well.”

Not only would the Nord Stream bombings result in the largest single human-created methane release event in history—but the security concerns associated with the incident rocketed around the transatlantic community, when, just days later preliminary forensic investigations uniformly pointed to “detonations” and “gross sabotage.” (Poursanidis, Sharanik, and Hadjistassou 2024; Lehto and Ringstrom 2022)

While the Nord Stream sabotage incidents were not the first examples of physical sabotage against energy and critical infrastructure in the European offshore in the past decade, they certainly captured the public imagination more than any other single incident to date—leading to multiple narratives regarding responsible actors, and fueling debate on how European countries can best ensure that offshore energy and critical infrastructure can be protected in a rapidly degrading global security environment.

The Nord Stream sabotage reinforced the need for transatlantic policymakers to take the threat of physical attacks against energy infrastructure just as seriously as they had begun to address threats to supply security, monopolistic practices, and strategic corruption that had been tools largely used by the Russian Federation to undermine Europe’s energy and national security interests for decades. And those policymakers would need to move fast given the rapidly growing list of energy and critical infrastructure sabotage across the continent.

Bolstering European Energy Security

European dependence on Russian energy resources has been a key national security concern for policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic dating back to the Soviet era. Since Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rise to power just over 25 years ago, the Russian Federation has regularly used energy as a geopolitical weapon.

Especially over the past 15 years, Putin’s Kremlin has used its traditionally dominant position in the European natural gas market to extract political concessions from European states through the threat and use of gas cutoffs; it has conducted monopolistic practices and utilized lawfare in an attempt to undermine European Union market liberalization efforts; and it has eroded democratic resilience through the promotion of strategic corruption and elite capture within European democracies related to Russian energy infrastructure proposals like the Nord Stream pipelines (Balmaceda et al. 2021; MacFarquhar 2014; Miles 2018; Michel, Schmitt 2022).

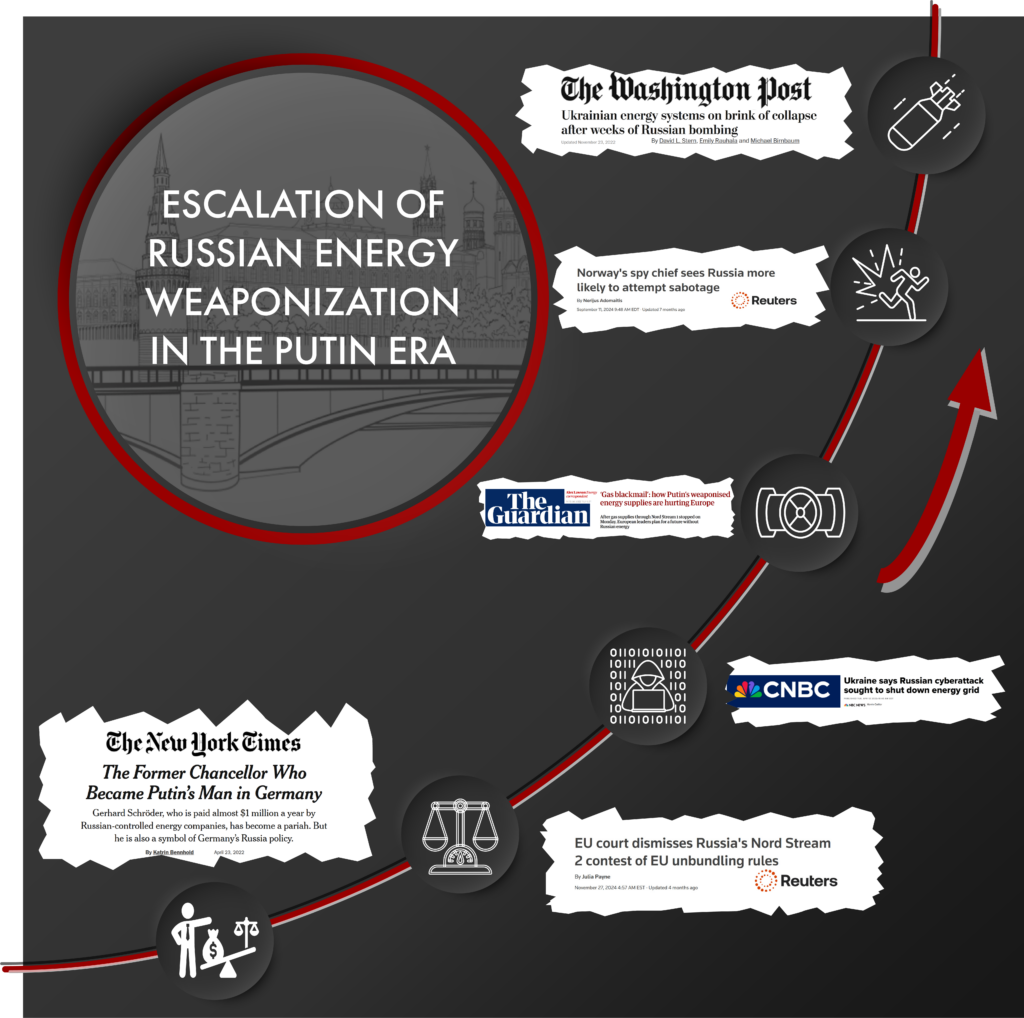

Figure Design: B. L. Schmitt / Template and Illustration Credits: Petr Vaclavek, Tuna salmon, Icons-studio, SkyLine, Genestro, Dewi, AxelBlogoodf – stock.adobe.com”

During this same period, policymakers in the European Union and the United States have focused on blunting Russia’s weaponization of energy by supporting policies that promoted the deployment of energy diversification infrastructure and antimonopoly regulations, with the aim of undermining Russa’s ability to effectively utilize a dominant market position to threaten energy poverty across the continent. (European Council 2025; Thompson Reuters 2025) Figure 1 illustrates the five primary pillars of contemporary European energy security that transatlantic policy makers have focused on over the past decade to deter Russia’s ongoing multispectral weaponization of energy.

Not So Secure

Since the weeks leading up to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the characteristics of Russian energy weaponization became both broader and more dramatic in their impact. The escalation of Russia’s use of energy as a weapon over time has moved from security of supply threats and strategic corruption in the lead up to 2022, to the dramatic tactics that are now ongoing.

These current tactics include military strikes to destroy Ukraine’s civil energy network—likely aimed at exacerbating an already widespread humanitarian crisis across the country—and physical sabotage actions against energy and critical infrastructure installations across NATO member states—likely aimed at undermining European resolve to provide support for Ukrainian victory.

This is not to say that transatlantic leaders did not long suspect the real potential that Putin’s Russia might one day resort to the destruction of energy and critical infrastructure as a means of escalating pressure against European democracies. A former senior U.S. government policymaker with expertise in European energy and security issues emphasized that:

“Across multiple administrations, we worked to support European energy security, especially focusing on helping Europe diversify its supplies. But we also assumed Putin had a long list of physical infrastructure in the West—including energy infrastructure—that he would be prepared to take out someday. Why would he limit himself to cutting off (or threatening to cut off) oil, gas, or electricity supplies when he could physically damage or disrupt pipelines, cables, hydroelectric dams, or other key infrastructure?”

Such sage predictions have come to pass over the past three years. As expected, Russia continued to follow its long-term supply security threat strategy, since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. A typical pathology of these supply threats includes the Kremlin linking the threat of natural gas cutoffs linked to geopolitical demands and then blaming those same cutoffs—if they come to pass—on some “technical” issue to establish plausible deniability.

Elements of these pathologies appeared in many of Russia’s dramatic cutoffs in recent years, such as in the partial and then full cutoff of the Nord Stream 1 natural gas pipelines between June and September 2022 (Deutsche Welle 2022; Lawson and agencies 2022).

Added to these supply cutoffs, however, was the launch of what could possibly be best described as Nordic media characterized in 2023: a skyggekrigen or “shadow war”—consisting of an ever-growing list of onshore and offshore incidents that have resulted in the physical damage of energy and critical infrastructure across the continent (NRK TV 2025).

Since the beginning of 2022—just weeks before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine—through to the present, there have been dozens of reports of damage to energy, telecommunications, and transportation infrastructure across the territory of NATO member states.

While many of these incidents remain under investigation, there have already been a significant number of cases in which European security officials have publicly attributed acts of sabotage to either Russian actors, or non-Russian nationals who have been recruited by Russia’s military intelligence, the GRU, to conduct a wide spectrum of infrastructure damage on NATO soil (Amran 2024).

‘Hybrid Threats’ or ‘Shadow War’?

Whether or not this latest stage of Russian energy weaponization should be considered “hybrid threats,” “terrorism,” or simply “war” may be subject to debate. The terminology used is not merely an academic exercise—it has direct policy implications regarding the sort of deterrence and response policies that are merited, and decisions ultimately made by policymakers to respond.

Beyond national security implications, energy policy decision-making is impacted by the characterization of these incidents. For example, Russian culpability for many of these energy infrastructure attacks would diminish any potential future European policy support or justification for returning to an energy “business as usual” import strategy vis-à-vis Russian oil and gas resources.

Speaking in response to a question posed for this digest at an on-the-record Council on Foreign Relations event on the margins of the July 2024 NATO Summit in Washington, D.C., Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen expressed the dilemma facing European leaders on how best to contextualize energy and critical infrastructure incidents within the broader geopolitical context, explaining:

“[W]hen you were listing some of the events we have seen just in a few months, it sounds like a bad movie, right? And I think that’s our main problem… It was a bit the same feeling I had before the attack on Ukraine. It was like we could not understand that Russia was going in[to] a full-scale war in Europe, but they were… I think they are attacking us every day now, not only on critical infrastructure, hybrid attacks, cyberattacks, disinformation, but also on migration… All of it is a part of modern warfare. I mean, that’s what we are looking into. So I think we have to take it much more seriously, and it has to be prioritized in NATO, because I think we have to look at it as an attack on us instead of just, well, now, something again happened, and again, and again, and again. So, I think we are being too friendly in our reaction to this… we are simply being too polite.”

According to Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørv, professor of security and geopolitics at the Arctic University of Norway (UiT), viewing Russia’s multispectral threats as linked—as described by Frederiksen above—is appropriate because “…we cannot see Russian activities as isolated events, but rather all part of a broader strategic objective to weaken western democracies and/or make some regions unstable enough to not be able to withstand larger, more militarized incursions.”

Gjørv, who leads a research group at UiT called “The Grey Zone,” which focuses on Arctic security, hybrid threats, warfare, and total defense added, “that is how hybrid threat activities work—multiple activities that together, over a period of time and within a given context—will weaken the target society ideally without going over the ‘threshold’ of military intervention or Article 5.”

Still, after many years of “hybrid” threat activities emanating from Moscow against the West, security experts may be approaching a semantic turning point on how these activities are categorized. For example, U.S. Army Lt. Gen. (Ret) Ben Hodges, who served as commander of the U.S. Army in Europe from 2014 to 2017, emphasizes that he “no longer think[s] of these Russian activities as ‘hybrid,’ but as a part of the spectrum of Russian warfare. They are constantly at war with us, even if we don’t acknowledge it, and are using different parts of that spectrum based on objectives and conditions.”

Figure Design: B. L. Schmitt / Template and Illustration: Petr Vaclavek, Terriana, Icons-studio, SkyLine, Genestro, Dewi, Cetacons – stock.adobe.com / Media Headlines: New York Times; Reuters “EU Unbundling”; CNBC ; The Guardian; Reuters “Sabotage”; The Washington Post

As for energy and critical infrastructure sabotage in this context, Hodges explained his view that “the use of sabotage is as much a part of the Russian way of war, as are rocket and missile attacks and ground assaults by tanks and BMPs.” Figure 2 illustrates the ever-escalating intensity and scope of Russian energy weaponization during the Putin era.

Speaking at the 2024 Riga Conference, then Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis took the linguistic importance of what democratic leaders call such acts by Russia a step further and emphasized his point on social media by asking “[W]hy do we call it ‘hybrid warfare’? Because if we called it terrorism, then we would have to do something about it.” (Landsbergis 2024)

A Rude Awakening

Sabotage attacks in which attribution has been possible since 2022 have mostly taken place against European onshore critical infrastructure, where, even in remote locations, infrastructure monitoring and the collection of forensic evidence can be relatively straightforward compared to offshore environments. Just a few examples of the wide range of incidents, sabotage methods, and infrastructure targets that have been reported on European soil, include:

- May 2025: A cache of explosives and detonators that was found deliberately buried next to a section of NATO’s Central Europe Pipeline System (CEPS), which has been in operation since the Cold War to provide oil and refined products to support NATO operations across its Western European reach (Schmitt 2024; Bewarder, Flade, and Schmitt 2024; NATO 2021);

- July 2024: A cell communications tower operated by Finnish telecommunication provider Elisa in Janakkala near Helsinki, Finland was knocked down following what authorities credit as “vandalism” when the tower support guy wires were found cut (YLE News 2024);

- July 2024: An arson attack on a cable shaft supporting DeutscheBahn rail lines near Bremen, Germany was responsible for a train outage in northern Germany (DPA 2024);

- August 2024: Reports in Germany emerged that long-range, military-grade surveillance drones had been tracked by German authorities operating over the ChemCoast Park in Brunsbüttel, Germany, adjacent to the Brunsbüttel floating LNG facility—the onshore pipeline that was itself damaged in a separate sabotage action in late-2023 near Hetlingen, Germany (Der Spiegel 2024; Quecke 2024);

- September 2024: A cable in Norway linking a “…jammer [that] had been set up at the far northern island [of Andøya] in connection with an international exercise…” had been found “…cut and destroyed…” according to reports from The Barents Observer (Stallesen 2024).

From the many onshore and offshore energy and critical infrastructure damage incidents that our team has tracked for the past two years, some trends emerge:

Attribution can be challenging. A minority of incidents have thus far been positively attributed by authorities to be the result of any actor, and in some cases, speculation can cause debates regarding whether a given incident was deliberate sabotage or else the result of accidental means or technical fault.

Indeed, it is useful to remember that not every incident of suspected sabotage considered by our team may ultimately be shown to be the result of a sabotage activity at investigation end. However, experts have highlighted that there also may be political motivations to (at least initially) characterize a deliberate incident as an “accident” given a reticence to “escalate” the state of the ongoing conflict with Russia beyond Ukraine’s boundaries.

Nationality can be disconnected. While European security authorities have attributed suspected sabotage plans to Russian actors, the use of non-Russian nationals has also been a hallmark of many of these attacks.

For example, a Russian national with “extensive ties to FSB and GRU officers” was arrested in France for plotting “destabilizing” acts to disrupt the Paris Olympics in July 2024. The trend of Russia’s GRU recruiting non-Russian nationals (such as via social media apps like Telegram) to carry out sabotage actions has been reported across a number of European nations, including examples of (Dobrokhotov, Weiss, and Grozev 2024):

- Citizens from the Baltic states recruited by the GRU “to vandalize and set fire to targets in the West,” according to Latvian and Estonian court documents (Springe, Roonemaa, and Weiss 2024);

- The GRU targeting as recruits “young, marginalized people, often immigrants and mostly men” to carry out sabotage activities, including the case of a Ukrainian immigrant caught operating in Poland (Jeznach, Grove, and Pancevski 2024);

- The case of the arson of a Ukrainian-linked business in the United Kingdom, for which multiple British citizens were charged in April 2024 for “assisting a foreign intelligence service” (in this case, Russian intelligence) “as well as aggravated arson” among other charges (Keate 2024).

Targets and methods can widely vary. Suspected sabotage incidents in Europe since 2022 have included a wide range of targets, from natural gas pipelines and electricity grids, to telecommunications cables and cell towers, to rail and logistical hubs. Some incidents that have been stopped by the apprehension of suspects by European authorities before attacks could be perpetrated have explicitly targeted sites with links to the EU and U.S. logistical support of Ukraine’s military (Deutsche Welle 2024).

Moreover, the suspected sabotage methods have widely varied, with arson and cable cuts among the most frequent suspected methods. One of the authors of this report, Schmitt, wrote about his own experience with a still unattributed case of a German high-speed rail-line electricity cable being cut between Bonn and Frankfurt and (ironically) impeding travel associated with the research in this policy digest (Schmitt 2024).

Since early 2022, there has also been a growing list of high-profile incidents of damage against energy and critical infrastructure located in offshore environments, ranging from the Barents to the Baltic seas. Given limitations on the persistent monitoring required for total maritime domain awareness, the remoteness of these incidents, and the technical difficulty associated with subsea forensic investigations, most of these acts of suspected offshore sabotage have not yet resulted in official attribution.

As a result, a combination of Russian disinformation associated with the suspected sabotage incidents combined with multiple media narratives arising for many of these events, has set off heated debates in the policy, military, expert, and commercial maritime communities regarding potential mechanisms and culprits.

Recommended Policy Actions

The pace of energy and critical infrastructure sabotage across the European continent only grew since the 2022 bombings of Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2. If policymakers do not elevate the policy, technological, and defense steps needed to deter physical sabotage threats from the Russian Federation (or any other actor), then there will be significant public degradation in the confidence in authorities to ensure energy security across the Transatlantic community.

Such an outcome will have direct negative impacts on a much wider array of policy areas, including support for European defense and Ukrainian victory, and countering Russian malign influence across the European energy sector.

If insufficient action is taken to deter further energy infrastructure sabotage, we can also expect less public support for renewable energy infrastructure deployment. We highlight in our report a real-world example of this: following the Nord Stream attack, local farmers on Bornholm began opposing offshore wind power over concerns that new installations might become targets of sabotage.

Figure 3 provides images of two such signs against the development of offshore renewable energy infrastructure out of concerns that such facilities could become the future targets of sabotage operations.

Photo Credit: B. L. Schmitt

Moreover, an insufficient response will likely embolden other authoritarian nations around the world, most notably the People’s Republic of China, to use similar subsea infrastructure attacks to undermine the national security of democratic states across East Asia, including in the run up to any possible future military action taken by Beijing against Taiwan.

Clearly, the multidisciplinary nature of the energy infrastructure sabotage threat in Europe requires a cross-cutting policy and technological response to enhance deterrence and ensure that broader risks associated with these attacks are mitigated to the greatest extent possible. Based on these findings, we recommend several multidisciplinary policy actions to respond to these sabotage acts against European energy and critical infrastructure:

1) NATO member states should invoke Article 4. NATO member states that have sustained energy and critical infrastructure sabotage attacks in which an official attribution has already taken place naming Russian government actors or non-Russian actors recruited and paid for by Russia’s military intelligence (GRU) or other intelligence services should collectively invoke NATO’s Article 4 provision.

Unlike Article 5, which is more suggestive of a military response, an Article 4 invocation could be send a strong public political signal. NATO’s Article 4 states that “the parties will consult together whenever, in the opinion of any of them, the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the Parties is threatened.” (NATO 1949)

2) The European Union should permanently phase out energy imports from Russia. Given the extent to which the Russian Federation under Vladimir Putin has weaponized European energy dependence over the past two decades, spanning from supply cutoffs to physical sabotage of energy infrastructure, the European Union should introduce permanent structural policy constraints precluding a return of Russian energy to Europe. Should this not be achieved, the Kremlin would almost certainly reintroduce strategic energy and national security vulnerabilities across the continent.

3) European authorities must counter Russian disinformation campaigns. The Russian Federation has coupled disinformation strategies that coincide with suspected energy and critical infrastructure sabotage events across Europe in recent years. European states must respond with early, consistent, and transparent statements and briefings by strategic communications authorities to counter these disinformation trends. Furthermore, public attribution can help inspire societal confidence in government responses to these incidents, when possible.

4) Transatlantic countries must coordinate protection efforts. Oskar Frånberg, associate professor of marine systems engineering at the Blekinge Institute of Technology in Karlskrona, Sweden emphasized that “given the current subsea threat environment across Northern Europe, it is more vital than ever to create a cross-competency forum to discuss maritime infrastructure protection issues from all relevant stakeholders.”

5) Leaders must embrace monitoring technology hardware and data analysis tools. Open-source intelligence data sources such as commercial AIS and satellite imagery can offer considerable insights regarding the nature of any of these offshore energy and critical infrastructure attacks. However, these systems are not a standalone panacea to fully characterize any given case and should be considered as vital supplemental systems, support for which should be expanded to bolster existing government classified intelligence tools.

Transatlantic countries must coordinate protection efforts as well as foster public-private partnerships to increase commercial monitoring technology hardware and data analysis tools to deter energy and critical infrastructure threats.

6) Climate leaders must integrate national security, energy security, and critical infrastructure security. Energy intermittency or security of supply issues related to geopolitically motivated cutoffs or physical sabotage of energy infrastructure can result in loss of support by electorates worried about the vulnerability of energy systems to attack.

If inadequately addressed, climate leaders may lose support for the deployment of the very onshore and offshore renewable energy installations that will be needed to ensure a rapid and just energy transition as soon as possible. To achieve such an objective, leaders must fully integrate national security, energy security, and critical infrastructure protection strategies into any future climate and energy transition policy frameworks.

Underwater Mayhem

This digest serves as a companion to the report entitled Underwater Mayhem: Countering Threats to Energy and Critical Infrastructure Across the NATO Alliance and Beyond. This report presents findings resulting from a multi-year research project launched at the University of Pennsylvania and focused on exploring global energy security trends as they pertain to energy and critical infrastructure protection from suspected sabotage operations, including those potentially involving the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China. Figure 4 depicts the cover of the Underwater Mayhem report.

Design and Photo Credit: B. L. Schmitt

The report provides analysis and policy guidance related to several of the highest profile acts of offshore energy and critical infrastructure damage that have taken place since early 2022 in Northern Europe, and globally, including:

- January 2022: The cut of a subsea fiber optic telecommunications cable connecting the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard with the Norwegian mainland (Staalesen 2022)

- September 2022: The destruction of three of the four trunklines comprising the Kremlin-backed Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipelines (Carrel and Jacobsen 2022)

- February 2023: The cutting of subsea telecommunications cables connecting the main island of Taiwan to the Taiwanese Matsu Islands (Wu and Lai 2023)

- October 2023: The destruction of the Balticconnector natural gas pipeline, as well as several subsea telecommunications cables connecting Finland and Estonia, and Estonia and Sweden (Sky News 2023)

- November 2024: The cutting of subsea telecommunications cables spanning the Baltic Sea between Lithuania and Sweden, and Finland and Germany (Pancevski 2024)

- December 2024: The damage of the Estlink2 subsea electricity interconnector cable, as well as several subsea telecommunications cables connecting Finland and Estonia (McHugh 2024)

- January and December 2024: The cutting of a subsea telecommunications cable linking Prince Edward Island to Newfoundland in the Cabot strait in northeastern Canada (The Canadian Press 2025)

- January and February 2025: The cutting of subsea telecommunications cables connecting Taiwan with the United States, the Republic of Korea, and Japan, and a cable between the main island of Taiwan with the Taiwanese Penghu Islands (Tobin, Ziao, Chang Chien 2025; Lee 2025)

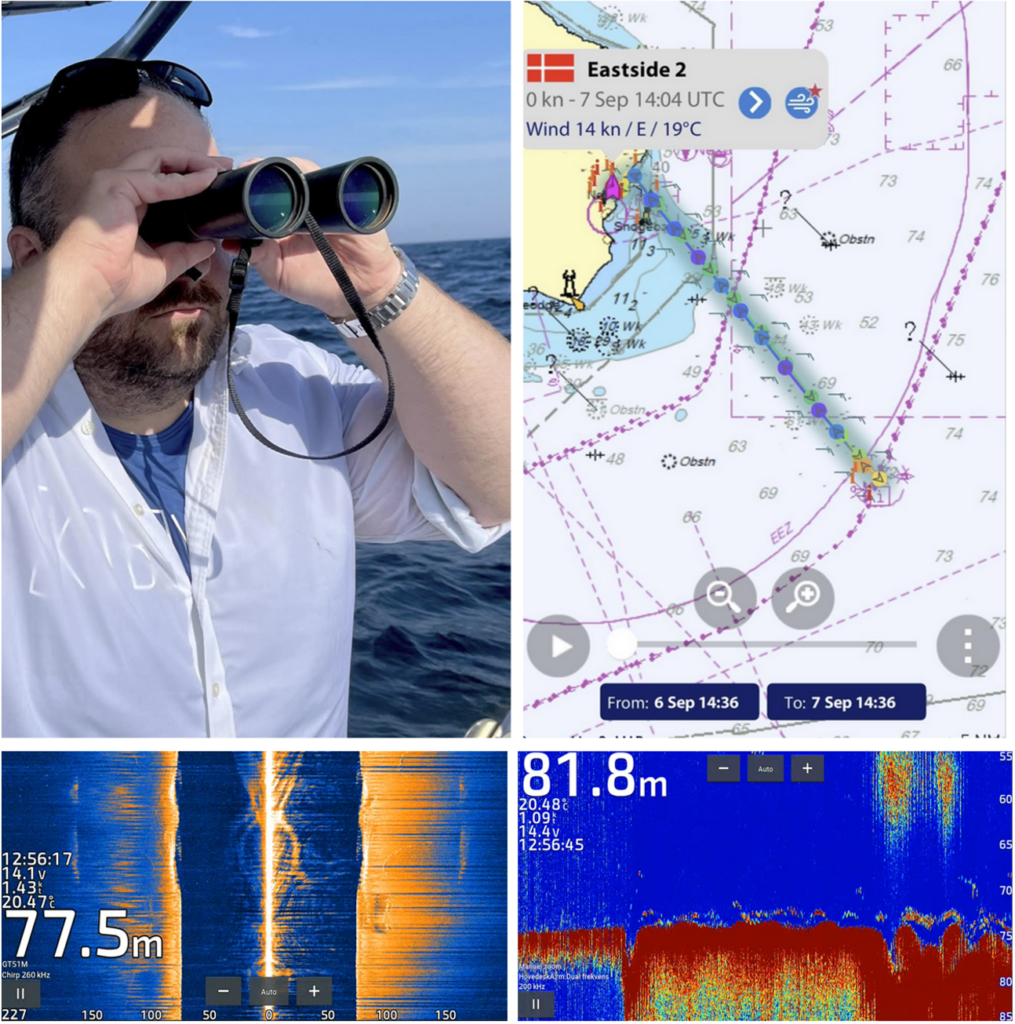

Underwater Mayhem, released in tandem with this policy digest, provides case studies focusing on the first two of these incidents. Our research is based on expert interviews, OSINT data analysis, and a review of public literature and documents.

Photo Credit: B. L. Schmitt

Photo Credit: B. L. Schmitt / AIS TRACK DATA: MarineTraffic / SONAR DATA: Eastside Marine, Nexø, Bornholm, Denmark

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy for providing the research funding to undertake this project, and the work of a stellar editorial and publications team—especially Lindsey Samahon and Mollie Simon—without which this project would not have been possible.

Schmitt would also like to wish a special thanks to Dr. Jakob Seerup for invaluable logistical support and discussions during the Schmitt’s three visits to the Danish Island of Bornholm during this research study.

Schmitt would also like to wish a special thanks to the Harvard-Ukrainian Research Institute, especially both Professor Serhii Plokhii and Dr. Emily Channel-Justice for their support of the years of preliminary research conducted while at Harvard University that served as the basis from which this project was launched, as well as the University of Pennsylvania Perry World House for supporting the research project programming and commercial satellite data license that were integral to the successful completion of this work.

Benjamin Schmitt

Senior Fellow, Kleinman Center and SASBenjamin Schmitt is a joint senior fellow at the Kleinman Center and the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Penn. He is also an affiliate of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and associate of the Harvard-Ukrainian Research Institute.

Alan Riley

Visiting Professor, College of Europe in NatolinAlan Riley is a visiting professor at the College of Europe, Natolin, Poland, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council. He is a recent EU advisor on energy security and a member of the Advisory Committee (the judicial panel) of the Energy Community.

Michał Kurtyka

Professor, College of Europe in NatolinMichał Kurtyka is a professor at the College of Europe in Natolin and Akademia Leona Koźmińskiego in Warsaw. He served as the first minister of Poland’s Ministry of Climate and as president of COP24.

The research for this digest was conducted within a multidisciplinary framework to mirror the interdisciplinary nature under which these incidents took place.

The research in this digest relied on:

- Field research conducted at or near the sites of where the two offshore attacks forming the case studies in this report took place across Northern Europe, including visits to: Longyearbyen, Svalbard in September 2023; onshore locations near both of the Nord Stream blast sites on the Danish island of Bornholm in July 2023 and January 2024; and an offshore research expedition to gather subsea sonar data of the Nord Stream 2 blast site southeast of Bornholm in September 2024;

- Interviews with dozens of experts on both sides of the Atlantic, including:

- Commercial leaders with expertise in offshore energy and critical infrastructure construction and operations

- Commercial ship operators and related maritime industry professionals

- Commercial and military divers and subsea demolitions experts

- Current and former naval, military, coast guard, and law enforcement professionals

- Current and former senior energy and national security officials

- Leading experts and academics focusing on European energy and national security issues

- Open-source intelligence (OSINT) analysis, including maritime automatic identification system (AIS) data (particularly the MarineTraffic AIS platform) and commercial geospatial intelligence platforms (particularly the Planet optical-wavelength satellite platform) (MarineTraffic 2025; Planet 2025)

- Review of literature, academic analysis, and press reporting related to these incidents, and related primary source documents

Additionally, some of the analysis and results presented in this report draw from ideas and text that were provided in oral and written testimony by Schmitt on September 24, 2024, as a part of a U.S. Senate and House joint Congressional hearing entitled “Russia’s Shadow War on NATO” held by the United States Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in the Cannon House Office Building in Washington, D.C (Schmitt 2024; Committee on Security and Cooperation in Europe 2024).

Amran, R. 2024. “Media: Special Unit of GRU Recruiting Saboteurs Through Social Media.” The Kyiv Independent. March 30, 2025. https://kyivindependent.com/media-special-unit-of-gru-recruiting-saboteurs-through-social-media/

Balmaceda, M., D. Fried, H. Hopko, K. Berzina, and B. L Schmitt. 2021. “Europe’s Gas Crisis and Russian Energy Politics: Experts Respond.” Harvard-Ukrainian Research Institute. November 1, 2021. https://www.huri.harvard.edu/tcup-commentary/europes-gas-crisis-russian-energy-politics

Bewarder, M., F. Flade, and J. Schmitt. 2024. “Der Ukrainekrieg ist hier laengst angekommen.” Sueddeutsche Zeitung. May 21, 2024. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/sabotage-russland-nato-pipeline-geheimdienst-1.7253897?reduced=true

Carrel, P. and S. Jacobsen. 2022. “EU Vows to Protect Energy Network After ‘Sabotage’ of Russian Gas Pipeline.” Reuters. September 28, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/mystery-gas-leaks-hit-major-russian-undersea-gas-pipelines-europe-2022-09-27/

Committee on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 2024. “Hearing: Russia’s Shadow War on NATO.” U.S. Senate and House Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). September 24, 2024. https://www.csce.gov/hearings/russias-shadow-war-on-nato/

Der Spiegel. 2024. “Drohnen ueber Industriepark – Behoerden gehen von Spionageangriff aus.” Der Spiegel. August 22, 2024. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/drohnen-ueber-chemcoast-park-brunsbuettel-behoerden-gehen-von-spionageangriff-aus-a-45de7019-b74e-456c-807c-6a72b021363b

Deutsche Welle. 2022. “Russia to Cut Nord Stream Gas Flow by Half.” Deutsche Welle. July 25, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/russia-to-further-slash-gas-deliveries-to-germany-via-nord-stream-pipeline/a-62588620

Deutsche Welle. 2024. “Germany Charges 3 over Alleged Russia Spying Plot.” Deutsche Welle. December 30, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-charges-3-over-alleged-russia-spying-plot/a-71187987

Dobrokhotov, R., M. Weiss, and C. Grozev. 2024. “Michelin Red Star: The Insider Reveals Identity of Arrested Russian Chef-Agent Who Planned “Destabilizing” Acts at Paris Olympic Games.” The Insider. July 25, 2024. https://theins.ru/en/politics/273350

DPA. 2024. “German Police Say Arson Causes Danage on Hamburg-Bremen Train Line.” DPA International. July 29, 2024. https://www.yahoo.com/news/german-police-arson-causes-damage-152727728.html

European Council. 2025. “Energy Union.” European Council. January 31, 2025. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/energy-union/

Jeznach, K., T. Grove, and B. Pancevski. 2024. “The Misfits Russia Is Recruiting to Spy on the West.” Wall Street Journal. May 15, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/the-misfits-russia-is-recruiting-to-spy-on-the-west-7417b2b5?mod=hp_lead_pos9

Keate, N. 2024. “Brits Charged with Helping Russia After Suspected Arson Attack on Ukraine-linked Firm.” Politico. April 26, 2024. https://www.politico.eu/article/britons-dylan-earl-jake-reeves-charged-help-russia-suspected-arson-attack-ukraine-national-security-cps/

Landsbergis, G. (@GLandsbergis) 2024. “Why do we call it “Hybrid Warfare?” Because if we called it terrorism then we would have to do something about it.”X (Twitter). October 19, 2024. https://x.com/GLandsbergis/status/1847586513229377681?mx=2

Lawson, A. and agencies. 2022. “Nord Stream 1: Gazprom Announces Indefinite Shutdown of Pipeline.” Guardian. September 2, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/sep/02/nord-stream-1-gazprom-announces-indefinite-shutdown-of-pipeline

Lee, Y. 2025. “Taiwan Detains China-linked Cargo Ship After Undersea Cable Disconnected.” Reuters. February 25, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-detains-china-linked-cargo-ship-after-undersea-cable-disconnected-2025-02-25/

Lehto, E. and A. Ringstrom. 2022. “Nord Stream Investigation Finds Evidence of Detonations, Swedish Police Say.” Reuters. October 6, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/kremlin-says-russia-not-invited-nord-stream-investigation-2022-10-06/

MacFarquhar, N. 2014. “Gazprom Cuts Russia’s Natural Gas Supply to Ukraine.” New York Times. June 17, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/17/world/europe/russia-gazprom-increases-pressure-on-ukraine-in-gas-dispute.html

MarineTraffic. 2025. “<MELKART-5> IMO: 9130183.” MarineTraffic. Accessed 2025. https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:313507/mmsi:273418680/imo:9130183/vessel:MELKART_5

MarineTraffic. 2025. “MarineTraffic Web Platform.” MarineTraffic. Accessed 2025. https://www.marinetraffic.com

McHugh, D. 2024. “Finland Stops Russia-linked Vessel Over Damaged Undersea Power Cable in Baltic Sea.” Associated Press. December 26, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/eu-finland-estonia-baltic-sea-power-cable-6741ef1ce9130602abac6214d7297717

Michel, C. and B. L.Schmitt. 2022. “How to Stop Former Western Leaders from Becoming Paid Shills for Autocrats.” Foreign Policy. February 15, 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/15/gerhard-schroder-gazprom-russia-tony-blair/

Miles, T. 2018. “Russia Loses Bulk of WTO Challenge to EU Gas Pipeline Rules.” Reuters. August 10, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/business/russia-loses-bulk-of-wto-challenge-to-eu-gas-pipeline-rules-idUSKBN1KV1VM/

NATO. 1949. “The North Atlantic Treaty.” NATO. April 4, 1949 (Accessed 2025). https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm

NATO. 2021. “Central European Pipeline System (CEPS).” NATO. August 30, 2021. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49151.htm

NRK TV. 2025. “Skyggekrigen: Brennpunkt.” NRK TV. Accessed 2025. https://tv.nrk.no/serie/brennpunkt-skyggekrigen

Pancevski, B. 2024. “Chinese Ship’s Crew Suspected of Deliberately Dragging Anchor for 100 Miles to Cut Baltic Cables.” Wall Street Journal. November 29, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/chinese-ship-suspected-of-deliberately-dragging-anchor-for-100-miles-to-cut-baltic-cables-395f65d1

Planet. 2025. “Planet Web Platform.” Planet. Accessed 2025. https://www.planet.com/

Poursanidis, K., J. Sharanik, C. Hadjistassou. 2024. “World’s Largest Natural Gas Leak from Nord Stream Pipeline Estimated at 478,000 Tonnes.” iScience CellPress Open Access. January 19, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004223028493

Quecke, F. 2024. “Suspected Sabotage at Regional German LNG Pipeline Might Cause Million-Euro-Damage – Report.” Clean Energy Wire. January 9, 2024. https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/suspected-sabotage-regional-german-lng-pipeline-might-cause-million-euro-damage-report

Schmitt, B. L. 2024. “Testimony: Russia’s Shadow War on NATO.” U.S. Senate and House Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). September 24, 2024. https://www.csce.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Schmitt-Testimony.pdf

Schmitt, B. L., 2024. “Wake Up NATO: It’s Sabotage.” Center for European Policy Analysis. June 12, 2024. https://cepa.org/article/wake-up-nato-its-sabotage/

Sky News. 2023. “Chinese Ship’s Anchor Caused Damage to Baltic Gas Pipeline, Finland suggests.” Sky News. October 25, 2023. https://news.sky.com/story/chinese-ships-anchor-caused-damage-to-baltic-gas-pipeline-finland-suggests-12992004

Springe, I., H. Roonemaa, and M. Weiss. 2024. “Exclusive: Inside Russia’s Latvian Sabotage Squad.” The Insider. July 10, 2024. https://theins.ru/en/politics/272989

Staalesen, A. 2022. “’Human Activity’ Behind Svalbard Cable Disruption.” The Barents Observer. February 11, 2022. https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/security/human-activity-behind-svalbard-cable-disruption/160886

Stallesen, A. 2024. “Military Experts Suspect Sabotage at Andoeya.” The Barents Observer. September 13, 2024. https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/security/military-experts-suspect-sabotage-at-andoya/166701

The Canadian Press. 2025. “Bell Says Subsea Cable from Cape Breton to Newfoundland was Deliberately Cut – Twice.” CTV News. February 19, 2025. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/newfoundland-and-labrador/article/bell-says-subsea-cable-from-cape-breton-to-newfoundland-was-deliberately-cut-twice/

Thompson Reuters. 2025. “Practical Law Glossary – Third Energy Package.” Thompson Reuters Practical Law. January 1, 2025. https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-001-8222?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true

Tobin, M., M. Xiao, and A. Chang Chien. 2025. “Taiwan Says it Suspects a Chinese-linked Ship Damaged an Undersea Internet Cable.” New York Times. January 7, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/07/world/asia/taiwan-internet-cable-china.html

Wu, H. and J. Lai. 2023. “Taiwan Suspects Chinese Ship Cut Islands’ Internet Cables.” Associated Press. April 18, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/matsu-taiwan-internet-cables-cut-china-65f10f5f73a346fa788436366d7a7c70

YLE News. 2024. “Police Suspect Vandalism Behind Cell Tower Collapse in Haeme.” YLE News. July 29, 2024. https://yle.fi/a/74-20101909