PA Future Utility Part IV: How States are Approaching the Future Utility Issue

So far, the Kleinman Center’s Future Utility Policy Digest series has provided background on electric utility regulation (Part I), an overview of challenges and opportunities being experienced by electric utilities (Part II), and begun to explore different philosophies of electric utility change (Part III). In Part IV of the series, we begin to examine how states are approaching the future utility issue.

Introduction

There is no single “correct” answer to the question of “what should be the utility business model of the future?” Each state or jurisdiction has its own set of unique circumstances that may require a tailored approach. Timing is also a consideration as some states may not need, or be ready, to look at the future utility issues immediately, whereas others require a more expeditious approach. There are also gradients of remedies available to address these utility issues, ranging from incremental to transformative approaches. In determining the right approach for a particular state, assessing and understanding the specific challenges facing the state, utility and non-utility stakeholders, is useful prior to developing potential solutions.

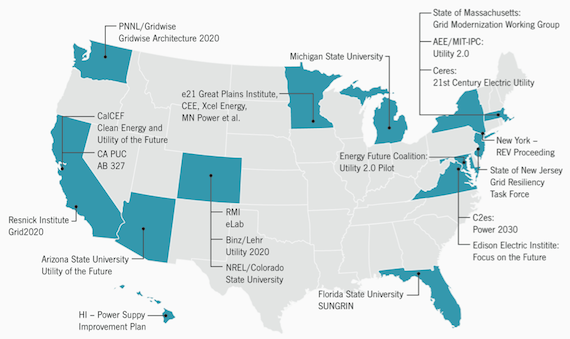

The future utility discussion is happening across the country, in various forms. Some states are moving forward with incremental (controversial or non-controversial) changes to their business models, others have started by developing investigations or stakeholder processes to gather information about the potential for transformation, some states have decided to launch full scale restructuring of the utility business model and several have employed more than one of these strategies. Below are examples of just some of these state actions.

Incremental Approaches

Part III in the Future Utility Policy Digest series covered a wide range of incremental approaches to revising the existing cost of service model. Some of these approaches have been more or less controversial. Here, we provide brief information about two of the more controversial changes, increasing fixed monthly charges and reducing net metering compensation, both aimed at addressing the revenue erosion effect.

The push to increase fixed charges is a national trend with numerous utility proposals pending and new efforts being filed regularly. Some of these proposals have been successful. For example, in 2014, Wisconsin regulators voted to approve monthly fixed charge increases for We Energies (from $9 to $16 per month), Madison Gas and Electric (from $10.44 to $19) and the Wisconsin Public Service Corporation (from $10.40 to $19). However, other efforts have been unsuccessful. For example, in 2015, regulators in Minnesota denied a request by Xcel energy to increase residential fixed charges from $9 to $10.25 per month, after approving several fixed charge increases in the past.1 Recently, California regulators denied utility requests to impose fixed monthly charges, instead establishing minimum bills ($5 for low income, $10 for all other customers) and allowing the utilities to request monthly fixed charges in future rate cases if certain conditions are met.2

Another national trend involves efforts to reduce net metering benefits and place new fees on distributed energy system owners. In 2013, Arizona regulators placed a $0.7 per kilowatt grid connection fee on new net metered customers, the first such fee of its kind in the U.S.3 Broader efforts to reform net metering policies by Arizona utilities have been unsuccessful to date, after regulatory staff recommended these changes be pursued within full rate cases (as opposed to separate dockets).4 In 2013, the Idaho Commission rejected a proposal from Idaho Power to increase fixed charges for residential net metered customers from $5 to over $20 per month.5

Investigations into Transformation

Several states have chosen to start with a bottom-up approach, launching investigations, issuing executive orders and establishing stakeholder proceedings to gather information before moving forward with broader strategies. Arizona’s “Innovation and Technological Development’s Investigation” included a series of workshops to examine how emerging technologies could impact the electric utility industry and enable the Commission to understand potential regulatory issues.6 California’s “The Business Model for the Electric Utility of the Future” en banc educational discussion included expert panelists that explored how traditional utilities are being impacted by technology, grid, and service innovations, and identified options for addressing challenges.7 Maryland’s “Utility 2.0 Investigation and Grid Resiliency Task Force” were established by executive order and focused on ways to improve grid resiliency and reliability, including options for financing and cost recovery for needed capital investments.8 Massachusetts’ “Electric Grid Modernization Stakeholder Working Group” investigated policies to enable the state’s distribution utilities and customers to take advantage of grid modernization opportunities.9 Minnesota’s “e21 Initiative” is an example of a stakeholder collaborative convened outside of the regulatory commission, aimed at developing consensus recommendations on how to better align the ways utilities earn revenue with public policy goals, customer expectations, and changing technologies.10

Many of these states used these early investigations to inform and shape subsequent actions. For example, California went on to open several dockets covering future utility issues, including residential rates structures and time of use pricing, net metering reforms, distribution resource planning, and utility ownership of electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Fundamentally Transforming Utilities

GTM Research has identified three basic procedural pathways to utility transformation, essentially where the regulator, consumer, or utility takes the lead role in promoting change, while noting that some states may experience multiple pathways to transformation.11 In the regulator pathway, the regulator identifies a need to change the system – prior to consumer demand reaching a critical stage – based on non-consumer factors such as aging infrastructure or increased resiliency needs. For the consumer pathway, consumer demand prompts utility change, usually in the form of high DER penetration, high electricity prices, increasing demand charges, and other factors. For the utility pathway, the utility company seeks to take the lead in developing a transformational vision, in order to inform and drive a potential future regulatory agenda.

- Regulator Pathway – The New York Public Service Commission’s “Reforming the Energy Vision” (REV) proceeding represents a top-down, regulatory-driven approach to fundamentally restructuring the role of the distribution utility. In this process, the regulatory agency first laid out its vision of the utility of the future in an order,12 and then instituted a series of stakeholder processes aimed at achieving this vision. The REV order basically sees the utilities serving in the Smart Integrator role, with an expansion of competitive third party entities providing grid, DER and other services to customers. Track One of the REV stakeholder process examines overall system design and the role of the utilities (e.g. in enabling market-based deployment of DERs), while Track Two explores changes to regulatory provisions needed to implement the vision and align utility interests with public policy goals. Upon completion of these two tracks, the process is expected to move into an implementation period with ongoing stakeholder input. In addition, New York’s renewable portfolio standard and energy efficiency resource standard are set to expire at the end of the year. To replace the market mandate policies, New York has proposed a Clean Energy Fund in order to attract private capital and promote renewables and efficiency.13

- Consumer Pathway – Hawaii is an example of a state where consumer interest in distributed generation and advanced technologies is the main driver of utility business model change. According to the Hawaii PUC, many distributed technologies are more economic than the Hawaii Electric Company’s (HECO) avoided cost of generation at over $0.22/kilowatthour.14 High electricity prices are promoting customer interest in cost effective DERs and storage, creating shifting loads and operational challenges. In 2013, as part of a rate increase approval, the HI PUC observed that “…the HECO Companies appear to lack movement to a sustainable business model to address technological advancements and increasing customer expectations,” and warned that failure to establish such a model would result in the Commission being forced to employ a more arduous regulatory approach.15 The Commission also performed an evaluation of state renewable energy policy and procurement and found renewable energy deployment could deliver considerable net value to Hawaii consumers.16 In April 2014, the HI PUC rejected HECO’s integrated resource plan noting lack of strategic focus and progress towards a sustainable business model and issued its own roadmap of the future of Hawaii’s electric utilities in an attached exhibit.17 The HI PUC’s exhibit detailed principles for the utility to consider in developing required plans, and laid out a potential vision of the utility transforming into the Smart Integrator role. The Commission also issued complimentary orders and information to guide the HECO companies in transforming their business models to better achieve state public policy goals, such as the 40% renewable energy by 2040.18

- Utility Pathway – Duke Energy can be cited as an example of a utility taking action to define its future. In 2007, the company developed a “Utility of the Future” initiative focused on developing a smart grid regulatory strategy across the multiple states over which it operated.19 In 2014, Duke’s distribution business unit (functionally separate from Duke Energy Renewables that invests heavily in renewable energy technologies) committed $500 million to North Carolina’s solar energy economy by purchasing three new utility scale solar projects (128 megawatts) and entering into five power purchase agreements with solar developers (150 megawatts). These investments not only helped the regulated utility meet its renewable portfolio standard obligation, but signaled a greater commitment to the technology upside by investing in ownership, not just offtake. Duke is also exploring enhanced value to consumers by becoming a trusted energy advisor.20 While these actions do not represent a comprehensive vision of future utility business model, they signal utility-driven leadership in this area.

To date, there is no method of accurately predicting the future, no “correct” vision of the next generation utility business model, and multiple pathways in which states and stakeholders can engage to attempt to answer these important questions.

Christina Simeone

Kleinman Center Senior FellowChristina Simeone is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and a doctoral student in advanced energy systems at the Colorado School of Mines and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a joint program.

Interstate Renewable Energy Council, Inc, “Connecting to the Grid: 6th Edition,” 2009, available at http://www.irecusa.org/connecting-to-the-grid-guide-6th-edition/

Lehr, Ronald, “New Utility Business Models: Utility and Regulatory Models for the Modern Era,” American’s Power Plan, 2013, available at http://americaspowerplan.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/APP-UTILITIES.pdf

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “The MIT Utility of the Future Study, White Paper,” December 2013, available at https://mitei.mit.edu/system/files/UOF_WhitePaper_December2013.pdf

- Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, Press Release, “Minnesota Public Utilities Commission Acts on Xcel Energy’s Multi-Year Electric Rate Case”, March 26, 2015, available at http://mn.gov/puc/documents/pdf_files/press_release_xcel_ratecase_3-26.pdf [↩]

- Utility Dive, “Inside California’s Rate Restructuring Plan and the Battle for Fixed Charges Looming Over it”, Herman K. Trabish, July 13, 2015, available at http://www.utilitydive.com/news/inside-californias-rate-restructuring-plan-and-the-battle-for-fixed-charge/402117/ [↩]

- Utility Dive, “Arizona Sets First Rooftop Solar Fee in U.S.”, Rod Kuckro, November 15, 2013, available at http://www.utilitydive.com/news/arizona-sets-first-rooftop-solar-fee-in-us/195159/ [↩]

- Utility Dive, “TEP Drops Net Metering Reform Push, Will Wait for Rate Case”, Herman K. Trabish, June 23, 2015, available at http://www.utilitydive.com/news/tep-drops-net-metering-reform-push-will-wait-for-rate-case/401133/ [↩]

- Idaho Public Utilities Commission, Press Release, “Most of Idaho Power Net Metering Proposals Denied”, July 3, 2013, available at http://www.puc.idaho.gov/press/130703_IPCnetmeterfinal.pdf [↩]

- Arizona Corporate Commission, Staff Report “Inquiry into the potential impacts to the current utility model resulting from innovations and technological developments in generation and delivery of energy,” (December 19, 2014), Docket No. E-00000J-13-0375, located at http://images.edocket.azcc.gov/docketpdf/0000158970.pdf [↩]

- California Public Utilities Commission, “En Banc: The Business Model for the Electric Utility of the Future”, October 8, 2013, located at http://www.cpuc.ca.gov/PUC/Oct_8_2013_En_Banc_The_Business_Model_for_the_Electric_Utility_of_the_Future.htm [↩]

- Maryland Energy Administration, “Grid Resiliency Task Force: Weathering the Storm”, information available at http://energy.maryland.gov/reliability/ ; Energy Future Coalition, “Maryland Utility 2.0 Pilot Project”, information available at http://energyfuturecoalition.org/What-Were-Doing/Utility-20 [↩]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities, “Investigation by the Department of Public Utilities on its own Motion into Modernization of the Electric Grid”, Order D.P.U. 12-76, October 2, 2012, located at http://web1.env.state.ma.us/DPU/FileRoomAPI/api/Attachments/Get/?path=12-76%2f10212dpuntvord.pdf [↩]

- Great Plains Institute, e21 Initiative, information available at http://www.betterenergy.org/projects/e21-initiative [↩]

- GTM Research, “Evolution of the Grid Edge: Pathways to Transformation”, 2015, located at http://www.greentechmedia.com/research/report/evolution-of-the-grid-edge-pathways-to-transformation [↩]

- New York Public Service Commission, Order Adopting Regulatory Policy Framework and Implementation Plan, Case 14-M-0101 – “Proceeding on Motion of the Commission in Regarding to Reforming the Energy Vision,” , February 26, 2015, located at http://documents.dps.ny.gov/public/Common/ViewDoc.aspx?DocRefId={0B599D87-445B-4197-9815-24C27623A6A0} [↩]

- New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, Clean Energy Fund Proposal, Case 14-M-0094 – “Proceeding on Motion of the Commission to Consider a Clean Energy Fund,” , September 23, 2014, located at http://documents.dps.ny.gov/public/Common/ViewDoc.aspx?DocRefId={C8D962E7-04B5-4B2E-A04E-E66CB3E79FF1} [↩]

- Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. for the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, “Evaluation of Hawaii’s Renewable Energy Policy and Procurement, Final Report”, January 2014, http://puc.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/HIPUC-Final-Report-January-2014-Revision.pdf [↩]

- Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, “Decision and Order No. 31288, Maui Electric Company LTD rate case”, Docket 2011-0092, filed May 31, 2011, available at http://dms.puc.hawaii.gov/dms/OpenDocServlet?RT=&document_id=91+3+ICM4+LSDB15+PC_DocketReport59+26+A1001001A13F03B43854C1206218+A13F03B43854C120621+14+1960 [↩]

- Energy and Environmental Economics for HI PUC, January 2014 [↩]

- Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, “Decision and Order No. 32052 Regarding Integrated Resource Planning”, Docket No. 2012-0036, filed April 28, 2014, http://puc.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Decision-and-Order-No.-32052.pdf [↩]

- Hawaii Public Utilities Commission, Press Release, “PUC Orders Action Plans to Achieve State’s Energy Goals,” April 29, 2014, located at http://puc.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Press-Release-Summaries.2014-04-29.pdf [↩]

- McNamara, Will and Smith, Matthew, “Duke Energy’s Utility of the Future: Developing a Smart Grid Regulatory Strategy Across Multi-State Jurisdictions,” (2007) available at http://www.gridwiseac.org/pdfs/forum_papers/155_paper_final.pdf [↩]

- Utility Dive, “How Duke Energy is Becoming Your Trusted Energy Advisor”, Davide Savenije, February 21, 2014, available at http://www.utilitydive.com/news/how-duke-energy-is-becoming-your-trusted-energy-advisor/230548/ [↩]