In the transition to a post-carbon economy, there is a potential to unintentionally reinforce or extend previous injustices, or to create new ones. This digest explores tensions in balancing local responsiveness with coordinated national strategy.

At A Glance

Key Challenge

The tensions and trade-offs between the different scales of Just Transition thinking and action – from local to national and even international – means decision making pathways are contested.

Policy Insight

Coordinating local Just Transitions with national justice strategies requires a multi-scalar approach—integrating diverse perspectives and aligning goals and measurement across governance levels.

Introduction

Decarbonization must happen at an unprecedented scale to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Many countries have set “net-zero” targets, showcasing their intent towards preventing further global warming. Yet achieving net-zero comes with both opportunities and risks. There is increasing consensus of the need for integrated approaches to net-zero that account for the environmental, economic, social, cultural and psychological dimensions of the transition to a post-carbon economy (Abram et al. 2020). Without this, there is potential to unintentionally reinforce or extend previous injustices throughout transitions, and to create new ones (Jenkins et al. 2017).

Increased awareness of justice concerns in the net-zero transition have begun to inform policy practice, most often under the umbrella term “just transition.” According to the IPCC, a just transition can be defined as “a set of principles, processes and practices that aim to ensure that no people, workers, places, sectors, countries or regions are left behind in the transition from a high-carbon to a low-carbon economy” (Pathak et al., 2022).

Under President Biden, the Justice 40 Initiative set a goal that 40% of the overall benefits of certain federal climate, clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing, and other investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution.1

The European Union’s Just Transition Mechanism provides funding to support the most affected regions to alleviate the socio-economic impact of the transition (Moesker and Pesch 2022), while South Africa’s Presidential Climate Commission has adopted a Just Transition framework as a planning tool, setting out the actions that the government and its social partners will take to achieve a Just Transition, and the outcomes to be realized in the short, medium, and long term (Presidential Climate Commission 2022).

Canada and Germany have implemented retraining programs and social protections for workers in declining fossil fuel industries and India and Indonesia are integrating Just Transition principles into energy transition roadmaps. All showcase what the Paris Agreement refer to the “imperatives of a Just Transition” during the move to a green, sustainable and socially inclusive post-carbon economy (UNFCCC 2015, 1).

While attention is uniting around the concept of a Just Transition,2 for many, its meaning remains elusive, or at least highly contested. The Just Transition is often seen to emphasise protections for fossil fuel workers, where its essence can be understood as “managing labour market transitions with an objective of creating decent jobs in a net-zero carbon economy while protecting and improving livelihoods and contributing to more equal societies” (Galgóczi 2018, 4).

The literature records critical issues addressed by the Just Transitions concept in line with this definition, including through place-based case studies (e.g., Nowakowska et al. 2021 and Weller et al. 2024) and a focus on key industries such as the coal (e.g. Snell 2018 and He et al. 2020; Upham et al. 2022). Parallel iterations have moved away from the labor union stance to reflect on the Just Transition term more broadly (Santos Ayllón and Jenkins 2023), considering a broader network of societal actors, structural inequalities and widespread participation (e.g., Abram et al. 2022).

Despite growing momentum, the literature also increasingly underscores the challenges of operationalizing the Just Transition, including political resistance (MacNeil and Beauman 2022) and the need for substantial financial investments (Newell and Mulvaney 2013; Santos Ayllón and Jenkins 2023), or impacts on vulnerable groups in the Global South (Svobodova et al. 2022).

High among the concerns are the tensions and trade-offs between the different scales of Just Transition thinking and action—from local to national and even international. Another tension is between the speed of climate action or energy transition, which is often positioned as being fast, and just and equitable outcomes, which tend to be understood as taking time and slowing progress (Newell et al. 2022).

Drawing on examples from the United Kingdom, and with a specific focus on Scotland as a devolved nation, this policy digest summarizes key findings derived from a series of research projects and engagements with UK policy officials as it answers the question: “how can responsiveness to local needs be balanced with a coordinated national Just Transition strategy?” It goes on to discuss several policy implications.

From Definitions to Principles

Some of the literature avoids a definition of the Just Transition where, for example, it could be positioned as a process where “governments design policies in a way that ensures the benefits of climate change action are shared widely, while the costs do not unfairly burden those least able to pay, or whose livelihoods are directly or indirectly at risk as the economy shifts and changes”—a working definition offered by the Scottish Just Transition Commission (Just Transition Commission 2021). Instead (or alongside), a principled approach can be taken, whereby the Just Transition is understood to align with several key principles. For Atteridge and Strambo (2020), the Just Transition can be defined according to seven:

- Actively encourages decarbonization

- Avoids the creation of carbon lock-in and more “losers” in these sectors

- Supports affected regions

- Supports workers, their families and the wider community affected by closures or downscaling

- Cleans up environmental damage and ensure that related costs are not transferred from the private to the public sector.

- Addresses existing economic and social inequalities

- Ensures an inclusive and transparent planning process

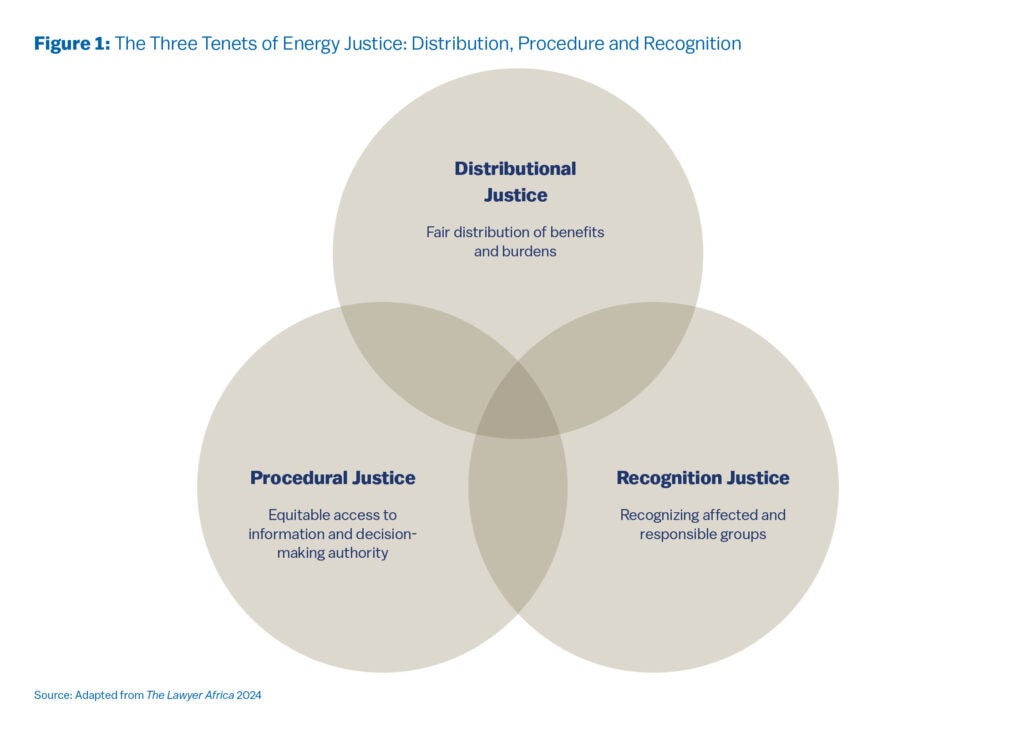

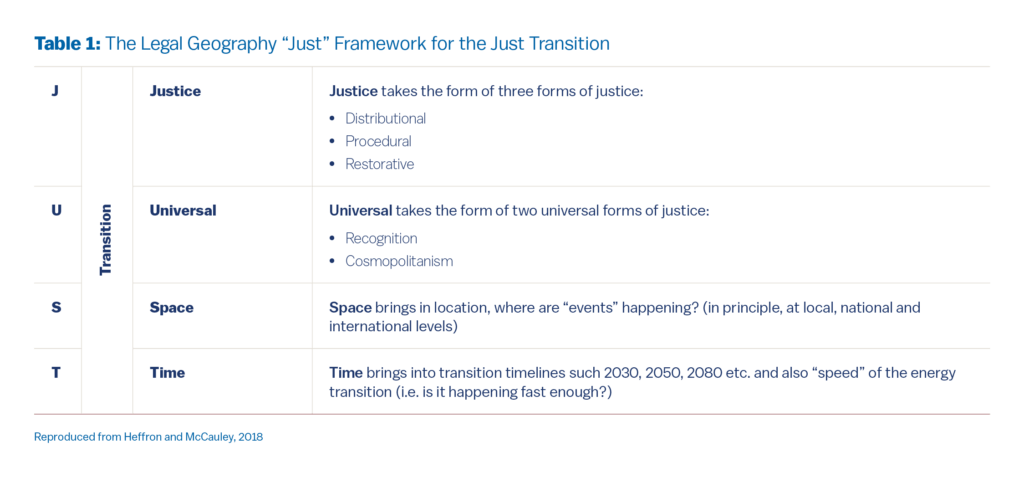

Closely related energy justice frameworks use a tenet approach (Figure 1 and Table 1), whereby just energy transitions are understood to be either constrained or enabled by a combination of distributional justice (a concern for infrastructure siting and energy access), justice as recognition (a concern for both who is affected and who is marginalised) and procedural justice (a concern for the decision-making processes and their fairness). Alongside policy practice, which defines the Just Transition precisely, these frameworks are increasingly popularized as policy structures applicable at a range of scales (e.g., by the European Environment Agency (2023) or for communities (Forman 2017)).

Principled and tenet approaches allow flexibility in the definition of Just Transition interests; flexibility that recognises that Just Transitions are highly contextualized and variously defined. These different definitions across scales, revealed by and understood through these frameworks, form the basis of the next reflections.

Tensions Across Scales, Places and Sectors

Tensions around Just Transition arise from the complex interplay of local, national, and sometimes global priorities, often creating conflicts in the design and implementation of equitable policies (Anderson and Johnson 2024). At the local level, communities and workers directly impacted by the phase-out of fossil fuels may prioritize immediate job creation and economic security, while national governments focus on broader policy frameworks that align with long-term decarbonization goals. Simultaneously, global climate targets, such as those set by the Paris Agreement, impose pressures on nations to act swiftly, which can be seen to marginalise local concerns. Such scalar misalignments risk fragmented strategies, where policies designed at one scale—whether local or national —fail to adequately address the concerns at another.

Research in Scotland demonstrates a localized concern for fuel poverty as a Just Transitions issue, reflecting its framing beyond concerns for fossil fuel workers. As of 2023, 34% of the Scottish population were fuel poor with 18.5% experiencing extreme fuel poverty. This figure rises to 44% for remote rural households (Scottish Government 2025). As a result of rising fuel prices during the Russian–Ukrainian conflict, a further set of households have experienced energy vulnerability and precarity for the first time (Hinson and Bolton 2024).

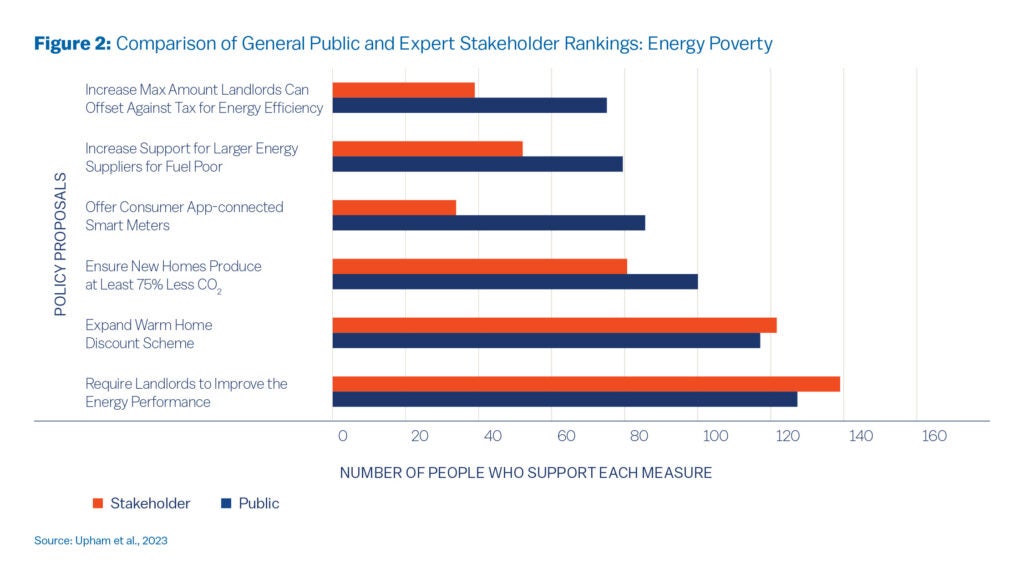

For fuel poor households, our research shows that the focus of justice in energy policy is often around affordability and home energy efficiency, with a preference for policy mechanisms that address these drivers of fuel poverty (Upham et al. 2023; Sovacool et al. 2023).

At a national level, the Scottish Draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan mentions the importance of fuel poverty (which is also the subject of the Fuel Poverty Strategy as a stand-alone document (Scottish Government 2021)) but also emphasises the national interest of decarbonizing 1 million homes by 2030 (Scottish Government 2023a).

The move toward domestic electrification through technologies such as heat pumps may increase rather than decrease household electricity costs depending on wider pricing factors (Xu et al. 2025). Therefore, the national interest of decarbonizing domestic heating may, unless tandem action is taken to reduce electricity prices, worsen experiences of fuel poverty, reinforcing local Just Transition concerns.

Recent fieldwork in Grangemouth, a community situated on the Firth of Forth 40 kilometers west of Edinburgh, Scotland, reveals scalar tensions too. The Grangemouth industrial cluster produces around 6% of Scotland’s emissions (as of 2021) through a combination of several assets in the downstream oil, gas, and petrochemical sectors, including Scotland’s largest container port and last oil refinery (Scottish Government 2023b).

Petroineous, the owner of the Grangemouth oil refinery, recently announced the closure of the facility in the second quarter of 2025, leading to the loss of around 400 jobs (Gibbs and Shibe 2024). The refinery’s closure will contribute significantly to Scotland’s ambitious climate targets but has raised widespread concerns for the impacted workers and the retention of their jobs and skills.

There are concerns, too, for the neglect of the wider Grangemouth area, including the town center, which faces so called “noxious deindustrialisation,” where employment is decreasing, inequality and precarity is rising, community ties are weakening, and exposure to socioenvironmental damage remains high (Feltrin et al. 2022). In this case, national emissions targets and priorities for the oil and gas transition sit in contention with local prosperity.

Fractured Governance

Navigating tensions in the Just Transition requires effective governance, but political arrangements are not always in alignment. Scottish versus UK Just Transition politics provide a contemporary example with relevance to the US.

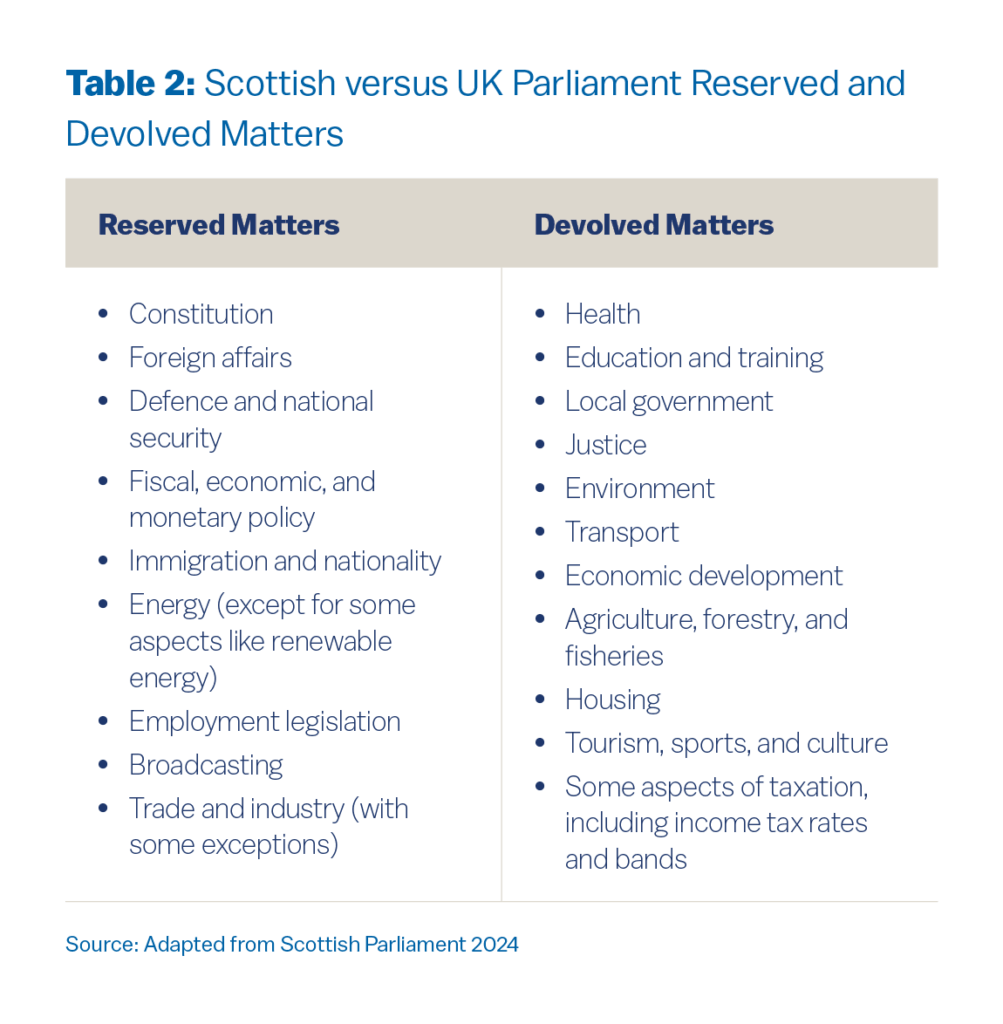

Scotland is a devolved nation in the UK and therefore Scottish policymaking is subject to so called “patrial devolution,” the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level (Leeke et al. 2003). The partial devolution of energy issues to Scotland has allowed the Scottish Government to play a proactive role in shaping its energy transition policies.

While the UK government retains control over key areas such as energy markets, regulation, and large-scale infrastructure, Scotland has authority over planning, renewable energy incentives, and environmental policy, enabling it to pursue ambitious climate goals (see Table 2). Scotland has leveraged these powers to advance renewable energy projects and to establish entities like the Just Transition Commission, which focuses on ensuring equity in its energy transition.

The devolution has also allowed Scotland to align energy policies with its broader climate ambitions, such as achieving net-zero emissions by 2045, five years ahead of the UK-wide target. Despite devolution, challenges persist due to overlapping jurisdictions, reliance on UK-controlled funding mechanisms, and constraints in shaping national energy policies. This includes in the Just Transition space.

(Source: Adapted from Scottish Parliament 2024)

Scotland has taken a leading role in Just Transition thinking. Attention to justice issues in the climate and energy policy area are elaborated upon on in Scotland’s Just Transition plan and recent research has established a national Just Transition evaluation and monitoring framework (Drabble et al. 2024), one of the first of its kind internationally.

Scotland has also established the eight National Just Transition Outcomes and the various other initiatives including the Just Transition Fund (JTF), a £500 million ten-year commitment that will support projects in the North East and Moray regions, which contribute toward the region’s net-zero transition.3

In comparison, our research suggests that UK’s approach lacks clear, binding mechanisms to ensure fairness and sufficient financial support for the most affected communities, highlighting the need for more robust, integrated strategies (Ghaleigh et al., 2021). This despite the UK’s “Net Zero Strategy” references the importance of delivering a fair transition and emphasizing investment in green jobs and skills development (HM Government 2021).

The partial devolution of powers to Scotland shares similarities with the federal and state system in the United States and tensions therein. Both involve a division of responsibilities between different levels of government, creating opportunities and tensions in policy implementation. Similar to the division of responsibility across Scotland and the UK, in the US, states have jurisdiction over areas like energy resource development, utility regulation, and renewable energy mandates, while the federal government oversees interstate energy markets, environmental standards, and national energy policy.

In both the UK and US systems, this division of power allows subnational entities to tailor policies to local needs and priorities. However, the nature of partial devolution also means that not all relevant levers for a Just Transition are under the purview of sub-state actors. Scottish interventions in the energy markets to mitigate price as a driver of fuel poverty, for instance, cannot be implemented. Indeed, conflicts can arise when national policies contradict or fail to support regional goals, such as Scotland’s push for ambitious climate targets or US states implementing aggressive renewable portfolio standards. Both systems reflect the complexity of balancing centralized coordination with regional autonomy in Just Transition concerns.

Clarity of Goals, Monitoring, and Evaluation

With varied priorities different scales, government (or indeed other actors) may measure Just Transition outcomes differently and potentially using different indicators. Alongside different definitions, these disparate measurement and evaluation approaches can reinforce fragmented approaches, making it difficult to develop cohesive policies or national and local standards.

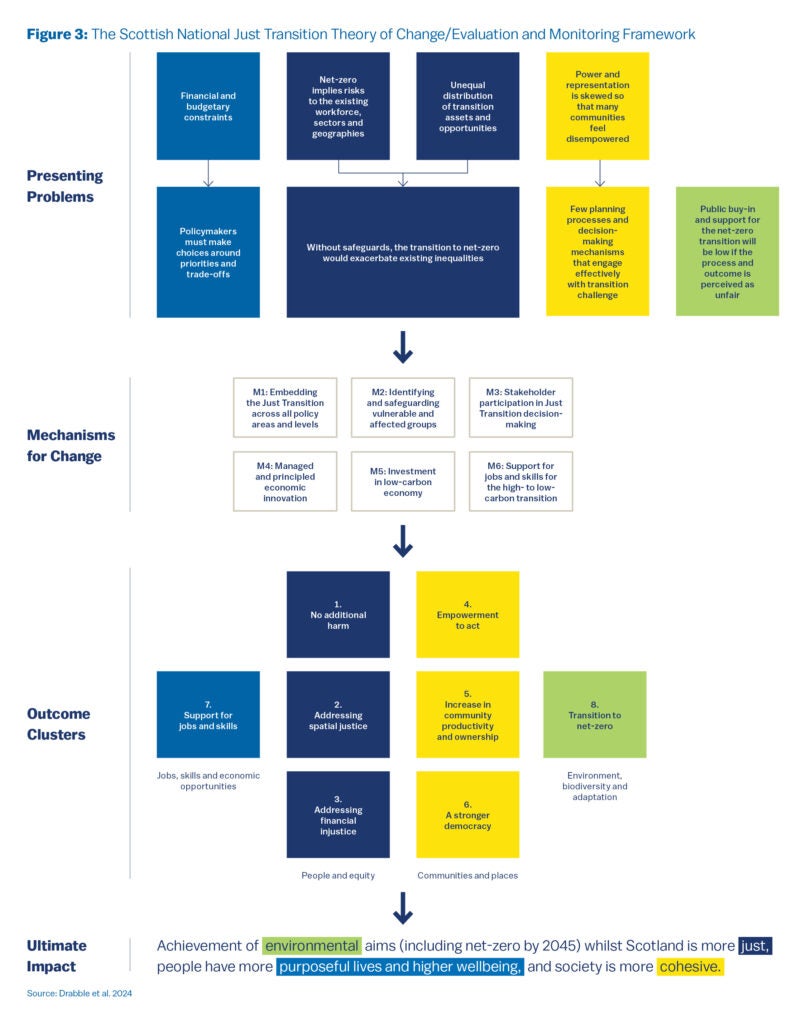

The importance of clearly defined goals, an understanding of the causal pathways behind Just Transition interventions—i.e., where it is possible to evidence that X intervention can lead to Y outcome—alongside appropriate datasets cannot be understated. Our research has led to the development of a national Just Transition evaluation and monitoring framework for Scotland (Figure 3) that demonstrates the links between presenting problems, the mechanisms that enable potential change, clusters of desirable outcomes and the ultimate aim for the Scottish Just Transition. This approach can be scaled down to local or regional applications where at that level, the detail of desired outcomes can be changed/prioritised and appropriate data selected.

To facilitate effective evaluation and monitoring via frameworks such as this, data will include quantitative metrics (e.g., percentage increases or decreases in fuel poverty per annum) and qualitative measures (e.g., a community’s sense of self-determination and empowerment in influencing and controlling Just Transition outcomes).

Recommendations for Policy and Governance

The multi-scalar challenge of Just Transitions is a seemingly intractable issue but must be resolved to ensure both positive local outcomes and national progress. This returns to the central question of: “how can responsiveness to local needs be balanced with a coordinated national Just Transition strategy?” Our research has demonstrated that coordinating local Just Transition needs with national justice strategies requires a multi-scalar approach that integrates diverse perspectives and aligns both goals and measures across governance levels. The following recommendations, several of which are adapted or replicated from Drabble et al. (2024), are intended to inform effective coordination:

- Implement adaptable guidelines: National frameworks should provide overarching guidelines and funding mechanisms while allowing flexibility for localized adaptations. Such approaches will account for regional disparities in resources, economic structures, and climate vulnerabilities, for instance, while keeping a national objective in sight.

- Establish a clear Just Transition vision statement and interim targets, focusing on a policy framework that is step-wise and implementable. This requires the agreement of priority areas and detailed activities across 5-, 10-, 15- and 20-year targets, for instance, with accountability for reaching these attributed to appropriate policy officials or mandated for external stakeholders. This will facilitate meaningful interventions that, with appropriate monitoring and evaluation, have demonstrable outcomes.

- Communicate the vision(s) held for the Just Transition and the approach used. The implications of the Just Transition will be widespread, affecting many stakeholders including for some, carrying more responsibilities and accountabilities and operate in new ways. To engender cross-stakeholder support, the vision and approach for the Just Transition must be clear and widely communicated. This will require new forms and styles of communication, including public outreach alongside a long-term commitment to meaningful participation.

- Coordinate policy ambition nationally and sub-nationally4 Much like the UK and Scotland, the relationship between the US state and sub-national governments have many interdependencies. There is significant opportunity to share best practice with the state level and advocate for collective outcomes. This may require new ways of working, including a Just Transition taskforce with cross-US representation.

- Facilitate active policy coherence across the full suite of policy, enabling a cross-sectoral approach that acknowledges both (1) all implicated policy strands and (2) all implicated scales, from local to national. This will ensure that tensions and trade-offs across policy areas are captured and managed and co-benefits are realized.

- Promote shared evaluation and monitoring frameworks: Transparent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are essential to track interventions, assess social and economic impacts, and ensure common language across a range of scales. Approaches that can be scaled down (or indeed up) across local and national contexts can help ensure that local priorities are recognized and captured and that their overall contribution to the national picture is understood. Regular reporting and feedback loops can help recalibrate strategies. This requires the development of a national scale evaluating and monitoring platform as well as cross-scale reporting channels to aid accountability, scrutiny and resource prioritization.

- Facilitate knowledge sharing: Establishing networks for sharing best practices and innovations among local, national, and international actors can help align efforts and address challenges. For example, local solutions for community-owned renewable projects could inform broader strategies. These networks can distribute insights from mechanisms like participatory budgeting, regional advisory councils, and stakeholder consultations.

By embedding justice considerations at every level and fostering collaboration, national and sub-national needs and priorities can become integral to coherent national Just Transition strategies

Kirsten E. H. Jenkins

Senior Lecturer, University of EdinburghKirsten Jenkins is a senior lecturer in energy, environment, and society within the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Jenkins is a 2024-2025 Kleinman Center Visiting Scholar.

Abram, S., E. Atkins, A. Dietzel, M. Hammond, K. Jenkins, L. Kiamba, J. Kirshner, J. Kreienkamp, T. Pegram, and B. Vining. 2020. “Just Transition: Pathways to Socially Inclusive Decarbonisation.” COP26 Universities Network Briefing.

Abram, S., E. Atkins, A. Dietzel, K. Jenkins, L. Kiamba, J. Kirshner, J. Kreienkamp, K. Parkill, T. Pengram, and L.M. Santos Ayllón. 2022. “Just Transition: A whole-systems approach to decarbonisation.” Climate Policy, 22(8), 1033–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2108365

Anderson, S.R. and M.F. Johnson. 2024. “The spatial and scalar politics of a just energy transition in Illinois.” Political Geography 112: 103128.

Atteridge, A. and C. Strambo. 2020. “Seven principles to realize a Just Transition to a low-carbon economy.” SEI Policy Report. Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm.

Drabble, D., K.E.H. Jenkins, R. Copeland, K. Horn, J. Cullen, M. Gieve, and A.S. Hanhe. 2024. “Measuring and evaluating success in the Scottish Just Transition.” Just Transition Commission.

European Environment Agency. 2023. “Delivering justice in sustainability transitions.” Briefing no. 26/2023. doi: 10.2800/228718.

Feltrin, L., A. Mah, and D. Brown. 2022. “Noxious deindustrialization: Experiences of precarity and pollution in Scotland’s petrochemical capital.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40(4), 950–969.

Forman, A. 2017. “Energy justice at the end of the wire: Enacting community energy and equity in Wales.” Energy Policy 107: 649–657.

Galgóczi, B. 2018. “From Paris to Katowice: the EU needs to step up its game on climate change and set its own just transition framework.” ETUI, The European Trade Union Institute. https://www.etui.org/publications/policy-briefs/european-economic-employment-and-social-policy/from-paris-to-katowice-the-eu-needs-to-step-up-its-game-on-climate-change-and-set-its-own-just-transition-framework Accessed: January 22, 2025.

Ghaleigh, N.S., S. Haszeldine, K. Jenkins, C. Bucke, K. Fairhurst, A. Sihota, and A. Sweeney. 2021. “The Future is Built on the Past: Just Industrial and Energy Transitions in the UK and Scotland.” University of Edinburgh.

Gibbs, E. and R. Shibe. 2024. “The Grangemouth Refinery Closure: Worker’s Perspectives.” The Just Transition Commission. https://www.justtransition.scot/publication/thegrangemouth-refinery-closure-workers-perspectives/

He, G., J. Lin, Y. Zhang, W. Zhang, G. Larangeira, C. Zhang, W. Peng, M. Liu, and F. Yang. 2020. “Enabling a rapid and Just Transition away from coal in China.” One Earth. 3(2): 187–194.

Heffron, R.J. and D. McCauley. 2018. “What is the ‘Just Transition’?” GeoForum 88: 74–77.

Hinson, S. and P. Bolton. 2024. “Fuel poverty.” (Number 8730), London: House of Commons Library.

HM Government. 2021. “Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener.” HM Government. ISBN

Jenkins, K.E.H., D. McCauley, and A. Forman. 2017. “Energy Justice: A Policy Approach.” Energy Policy 105: 631–634.

Just Transition Commission. 2021. “Just Transition Commission: A national mission for a fairer, greener Scotland.” Just Transition Commission. https://www.gov.scot/publications/transition-commission-national-mission-fairer-greener-scotland/

Leeke, M., C. Sear, and O. Gay. 2003. “An introduction to devolution in the UK.” Research paper. 03/84. London: House of Commons Library.

MacNeil, R. and M. Beauman. 2022. “Understanding resistance to Just Transition ideas in Australian coal communities.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 43: 118–126.

McCauley, D. and R. Heffron. 2018. “Just Transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice.” Energy Policy 119: 1–7.

Moesker, K. and U. Pesch. 2022. “The Just Transition fund—Did the European Union learn from Europe’s past transition experiences?” Energy Research and Social Science 91: 102750.

Newell, P.J., F.W. Geels, and B.K. Sovacool. 2022. “Navigating tensions between rapid and just low-carbon transitions.” Environmental Research Letters 17(4): 041006.

Newell, P. and D. Mulvaney. 2013. “The political economy of the ‘Just Transition.’” The Geographical Journal 179(2):132–140.

Nowakowska, A., A. Rzeńca, and A. Sobol. 2021. “Place-Based Policy in the ‘Just Transition’ Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions.” Land 10(10), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101072

O’Sullivan, K., O. Golubchikov, and A. Mehmood. 2020. “Uneven energy transitions: Understanding continued energy peripheralization in rural communities.” Energy Policy 138:111288.

Pathak, M., R. Slade, P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Pichs-Madruga, D. Ürge-Vorsatz, B.K. Sovacool et al. “Technical Summary.” Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.002.

Pinker, A. 2020. Just Transitions: a comparative perspective. Report prepared for the Just Transition Commission.

Presidential Climate Commission. 2022. “A presidential climate commission report: A framework for a Just Transition in South Africa.” The Presidential Climate Commission: Towards a Just Transition.

The Scottish Parliament. 2024. “Devolved and Reserved Powers.” The Scottish Parliament. https://www.parliament.scot/about/how-parliament-works/devolvedand-reserved-powers Accessed: January 30, 2025.

Scottish Government. 2021. “Tackling fuel poverty in Scotland: a strategic approach.” Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/publications/tackling-fuelpoverty-scotland-strategic-approach/

Scottish Government. 2023a. “Draft energy strategy and Just Transition plan.” Scottish Government. ISBN: 978-1-80435-805-4.

Scottish Government. 2023b. “Just Transition for the Grangemouth industrial cluster: discussion paper.” Scottish Government. ISBN: 978-1-83521-162-5.

Scottish Government. 2025. “Scottish House Condition Survey: 2023 key findings.” Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/news/scottish-house-conditionsurvey-2023-key-findings/

Santos Ayllón, L.M. and K. Jenkins. 2023. “Energy justice, Just Transitions and Scottish energy policy: A re-grounding of theory in policy practice.” Energy Research and Social Science 102992.

Snell, D. 2018. “Just Transition? Conceptual challenges meet stark reality in a ‘transitioning’ coal region in Australia.” Globalizations, 15(4), 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1454679

Sovacool, B.K., P.J. Upham, M. Martiskainen, K. Jenkins, G.A. Torres Contreras, and N. Simcock. 2023. “Policy prescriptions to address energy and transport poverty in the United Kingdom.” Nature Energy. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-023-01196-w.

Svobodova, K., J.R. Owen, D. Kemp, V. Moudrý, E. Lèbre, M. Stringer, and B.K. Sovcool. 2022. “Decarbonization, population disruption and resource inventories in the global energy transition.” Nature Communications 13: 7674.

The Lawyer Africa. 2024. “The concept of energy justice.” The Lawyer Africa. https://thelawyer.africa/2024/02/08/the-concept-of-energy-justice/ Accessed: January 30, 2025.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2015. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. 21st Conference of the Parties. Paris: United Nations.

Upham, P., B.K. Sovacool, and B. Ghosh. 2022. “Just transitions for industrial decarbonization: A framework for innovation, participation, and justice.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 167: 112699.

Upham, P. N. Simcock, B. Sovacool, and G.A. Torres Contreras, K.E.H. Jenkins, and M. Martiskainen. 2023. “Public support for decarbonisation policies: Between self-interest and social need for alleviating energy and transport poverty in the United Kingdom.” Energy and Climate Change (4): 100099.

Weller, S., A. Beer, and J. Porter. 2024. “Place-based Just Transition: domains, components and costs.” Contemporary Social Science 19(1–3), 355–374.

The Scottish Parliament. 2024. “Devolved and Reserved Powers.” The Scottish Parliament. https://www.parliament.scot/about/how-parliament-works/devolvedand-reserved-powers Accessed: June 19, 2024.

Xu, J., S. Mosbach, J. Akroyd, and M. Kraft. 2025. “Impact of heat pumps and future energy prices on regional inequalities.” Advances in Applied Energy 100201.

- Executive Order 14008 was rescinded under the second Trump presidency, terminating the Justice40 Initiative. [↩]

- While the language of Just Transition is often used as singular—“a Just Transition”—it is well recognised that there will be multiple intersecting transitions at any one time. [↩]

- Yet without the publication of the final Energy Strategy and Just Transition plan and more granular sectoral plans, which are delayed but anticipated in 2025, the Just Transition is largely positioned within a policy framework that is generic and aspirational rather than yet being embedded in an operational implementation approach (Drabble et al., 2024). [↩]

- Though it is recognised that federalism in the US is undergoing transformation, with increasing conflict between levels of government, including in the areas of climate and energy policy. [↩]