Looking Forward: Future Proofing SDG 7 Indicators Post-2030 for Equity, Outcomes, and Interlinkages

Although energy is central to sustainable development, existing SDG 7 indicators lack demographic disaggregation, rely heavily on input-level metrics, and fail to capture interlinkages with other SDGs. Drawing on existing examples of effective indicators across institutions, this brief outlines three recommendations to review the post-2030 SDG 7 framework.

At A Glance

Key Challenge

Current SDG 7 indicators have a limited ability to reflect equity, measure outcomes, and reflect interlinked advancements across other SDGs.

Policy Insight

There are several shortcomings in the current SDG 7. Existing indicators lack demographic disaggregation, rely heavily on input-level flows, and fail to interlink with other SDGs.

Introduction

This policy brief examines the shortcomings of the current SDG 7 indicators on affordable and clean energy and proposes forward-looking approaches to strengthen them in the post-2030 agenda. Although energy is central to sustainable development, existing indicators lack demographic disaggregation, rely heavily on input-level metrics such as financial flows, and fail to capture interlinkages with other SDGs.

These limitations obscure inequities in energy access, disconnect investments from measurable outcomes, and overlook the multidimensional role of energy in advancing broader development goals. Drawing on existing United Nations commitments under the 2030 Agenda, as well as insights from organizations such as ENERGIA and the United Nations Statistics Division, this brief outline three recommendations:

- refining indicators to ensure disaggregation by key demographic and economic factors

- reformulating input-based measures into outcome-oriented metrics

3) expanding target themes to integrate cross-sectoral linkages.

By situating these proposals within the 2026 High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) — the United Nations’ central platform for reviewing global progress on the Sustainable Development Goals — this brief underscore the importance of preparing equity-sensitive, outcome-focused, and interlinked indicators for the post-2030 sustainable development framework.

Background

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 7) on affordable and clean energy is structured around five core targets and six indicators. These focus on ensuring universal access to electricity and clean cooking (7.1), increasing the share of renewable energy (7.2), doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements (7.3), mobilizing international finance and technology for clean energy (7.a), and expanding infrastructure and capacity in developing countries (7.b). Progress is tracked through indicators such as the proportion of people with electricity and clean cooking access, renewable energy’s share of final consumption, energy intensity of GDP, and financial flows to clean energy.

This policy brief discusses the shortcomings of existing SDG 7 (affordable energy for all) indicators, acknowledging that while the existing SDGs cannot be revised, we should use forward-looking proposals and advocate for improved and robust indicators in a post-2030 sustainable development agenda, staying in line with the aspiration of “The Future We Want” (United Nations 2015).

The intended audience of this policy brief includes UN agencies and national policymakers preparing for the 2026 High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) review, as well as development banks and donors who rely on robust metrics to guide energy investments. This policy brief seeks to inform the dialogues at the 2026 HLPF, an event that will provide high visibility to the recommendations. The High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) is the UN’s central platform for reviewing progress on the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The 2026 HLPF will review several SDGs, including SDG 7, under the theme “Transformative, equitable, innovative and coordinated actions for the 2030 Agenda” (UN ECOSOC 2026). The 2026 HLPF is where global progress and challenges on energy access and transition are closely reviewed, drawing political, media, and civil society attention that can drive stronger commitments and momentum toward more ambitious energy policies, financing, and cooperation.

A secondary audience includes researchers and advocacy organizations who can leverage these insights to advocate for a more inclusive and effective SDG 7. By providing evidence-based recommendations on efficient and impactful indicators, the brief will help ensure that the 2026 review of SDG 7 goes beyond formal reporting and advocates for meaningful, real-world transformation in energy access, equity, and sustainability post-2030.

Problem Statement

Despite the centrality of energy to sustainable development, the current SDG 7 indicators are limited in three critical ways. First, the indicators lack demographic disaggregation even though, under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, member states committed to disaggregating SDG data by income, gender, geography, and other key factors to realize the pledge of “leaving no one behind” (UN 2015).

Unlike many other SDG indicators, which are broken down by gender, income group, or geography to capture the experiences of marginalized populations, SDG 7 remains one of the few goals without disaggregation as part of the main indicators. This obscures the uneven burdens and benefits of energy access across communities.

Second, one of the indicators, indicator 7.A.1, is largely input-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. It measures the financial flows to developing countries in support of the research and development of the clean energy transition. However, this metric should be revised into an outcome indicator, measuring who is benefiting from these research and development investments.

Finally, interlinkages between other SDGs and SDG 7 are weakly represented through the existing set of indicators. The absence of identifiable cross-sectoral indicators makes it difficult to assess energy’s true role in advancing multiple development priorities. Therefore, post-2030, it is imperative to refine existing indicators to make them more descriptive, reformulate indicators that are input-focused, and introduce new indicators where gaps exist.

Main Indicators Lack Disaggregation

Women made up only 22% of the global energy sector workforce in 2022, highlighting gender inequality in energy transition roles (Matano 2024). However, this disparity is not fully represented by any of the indicators. Disaggregated data is critical because national averages often hide inequalities. Energy inequality is inherently connected to the concept of justice, with the pursuit of energy justice serving as a central approach to addressing both energy and economic inequalities (Volodzkiene and Streimikiene 2025).

By involving all stakeholders in decision-making and representing them through disaggregated data, we can move toward a more sustainable and fair global energy system (Volodzkiene and Streimikiene 2025). Using indicators that reflect each country’s level of economic development and income inequality is essential for measuring energy inequality accurately and shaping effective policies (Volodzkiene and Streimikiene 2025). Therefore, enhancing data disaggregation is essential for fully implementing the SDG indicator framework and achieving the 2030 agenda’s goal of leaving no one behind (United Nations Statistics Division, n.d.).

Other SDGs (1, 4, 8, 10, 11, 16) already include such disaggregation by sex, age, geography, disability status, employment status, rural/urban location, wealth quintile, or migrant status to uncover disparities. For example, SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) has the indicator 11.2.1, which tracks the proportion of the population with convenient access to public transport by sex, age, and persons with disabilities. This allows those goals to track average progress alongside those who are being left behind. In contrast, SDG 7 indicators (7.1.1 electricity access, 7.1.2 access to clean fuels) do not have demographic disaggregation and report national averages only.

While the SDG 7 progress report in 2025 informed a few disaggregated data points such as the number of people without access to clean fuels and technologies by region, urban-rural distinctions, and by income, there is no demographic disaggregation, and these data points are not incorporated as main indicators.

The 2022 UN policy brief “Addressing Energy’s Interlinkages with Other SDGs” suggested that energy access data should, where possible, be disaggregated by gender, age, type of use (lighting, cooking, heating/cooling, water supply, or purification), urban versus rural location, educational level, and whether facilities are public or private.

While these recommendations provide valuable guidance, they have not been systematically integrated into the SDG reporting framework. Therefore, the 2026 HLPF should advocate for the integration of effective indicators post-2030, to capture real-world disparities in energy access, in line with the UN’s 2015 commitment to ensure inclusive and equitable development, leaving no one behind.

Indicators Track Input Instead of Output

According to Parsons et al. 2013, indicators can be grouped into five levels of measurement, as shown in Table 1. Input indicators measure the resources provided, such as money, expertise, or staff. Activity indicators break down the actions taken, including hiring, training, or building facilities. Output indicators measure the immediate results, such as cases heard or officers trained. Outcome indicators capture the benefits delivered, for instance, improved trust in police or better community safety. Finally, impact indicators tackle the higher-level goals, including access to justice for the poor or overall improvements in public safety.

Tracking outcomes and impacts allows indicators to signal when a strategy is not working as intended. While quantitative output indicators, such as the number of activities completed or products delivered, are useful for showing progress, it is equally important to assess the quality of those outputs. Strong outcome indicators go further by combining quantitative and qualitative measures, capturing not only how many people benefit from an intervention but also the nature and depth of those benefits (Parsons et al., 2013).

According to Mulholland et al. (2018), indicators are used because they link the present situation to desired future outcomes, showing how far a country is from achieving specific SDGs. Indicators allow progress to be tracked over time, guide policy decisions, and help governments, businesses, and civil society target limited resources where they are most needed. Therefore, the most appropriate indicator type for SDG monitoring is outcomes with occasional impacts included for long-term vision because SDGs are not about whether activities are carried out, but whether real-world change is happening. Outcomes measure the real benefits for people and societies, connecting outputs to lived experience.

Table 2 demonstrates that most SDG 7 indicators stop at the input and output level. Only two (renewable energy share, energy intensity) operate closer to outcome-level monitoring. Additionally, the instrument type indicator 7.A.1 is an input indicator, unable to successfully monitor any progress. Therefore, while most indicators can be disaggregated by relevant factors to be refined into outcome indicators, indicator 7.A.1 should be reformulated to track the actual improvements due to increased public finances.

Interlinkages Are Not Represented

The current SDG 7 indicators do not reflect intersectionality with other SDGs, even though they are designed to overlap with each other thematically and are statistically correlated. According to Fonseca et al. (2020), SDG 7 is significantly interlinked with eight other goals, most notably SDGs 3, 8, 9, 11, 13, and 16, indicating that progress on affordable and clean energy generates broad social and economic co-benefits.

The UN recognized the need for interlinked integration of economic, social, and environmental aspects to achieve a multidimensional sustainable development (UN 2015). Even then, SDG-7 lacks indicators that show how energy connects to other SDGs (Gebara & Laurent, 2022). For example, the 2025 Gender Snapshot produced by UN Women (2025) states that SDG7 has no gender-specific indicator.

Addressing this gap, ENERGIA and other organizations have advocated stronger interlinkages and synergies to maximize the benefits to other SDGs of action on energy (Maximizing the Benefits of Energy Action for Good Health, Gender Equality and Decent Work to Leave No one Behind et al. n.d.). The only promising strategy to meet the SDG 7 targets before 2030 lies in fostering synergies across SDGs, enabling simultaneous progress that is more resource-efficient and delivers greater economic and social impact (Powering the Sustainable Development Goals, 2024). SDG 7 interlinkages must be tracked and quantified for progress and to craft evidence-based interventions (UN 2022). Therefore, future revisions of indicators must consider and reflect the interlinkages.

Recommendations for a Just and Inclusive Agenda

Recommendation 1: Refine existing targets to ensure they represent disaggregated data points to uncover equity and distribution disparities

Table 3 shows how indicators can be revised or added to each existing theme for targets to ensure disaggregation, thus upgraded into outcome metrics. Besides, this disaggregation would also incorporate direct reflection of interlinkages with other SDGs. Most of disaggregation data are already reported by the UN to track advancements. Hence, these data points are available and can be easily recognized in the official list of indicators.

Recommendation 2: Reformulate the indicators of instrument targets to represent outcome metrics that can be useful to redistribute support resources

Instrument indicators should be reformulated to monitor the outcome expected by financial investments by sector and region. To track the success of financial investment in clean energy transition, it might be more useful to track renewable electricity generation (kWh) per unit of investment ($ million) in renewable energy, disaggregated by country/region and technology type. While most data points for these indicators are available, some data might not be available in the same format across the globe or be organized enough to be adopted immediately, adhering to the updated format.

Recommendation 3: Expand the themes of the targets to introduce indicators representing intersectionality with other SDGs

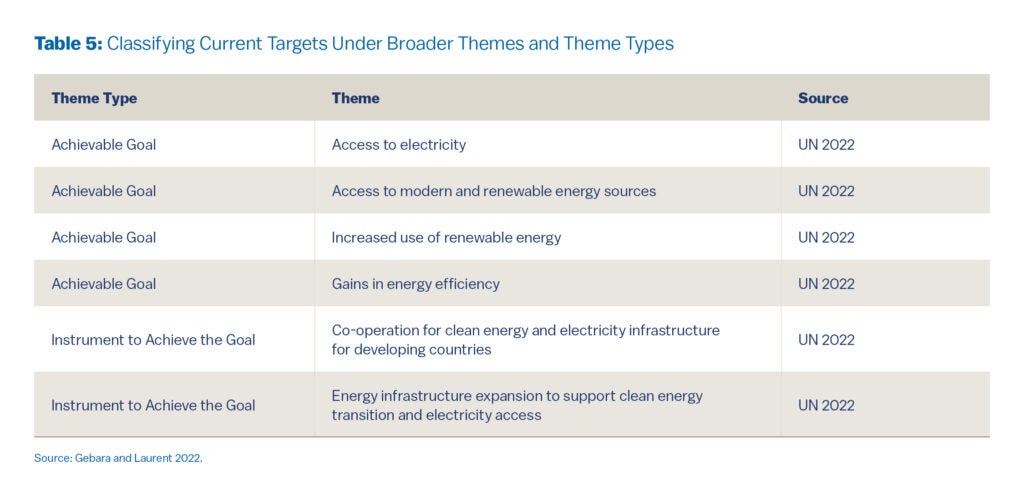

The lack of an expansive set of themes across targets limits the indicators from representing interlinkages between other SDGs. Themes are the general issues that a target addresses. Overall, the themes for each target can be unofficially classified broadly into two types, as shown in Table 1. According to Gebara and Laurent (2022), the first three targets are goals to achieve, and the last two are instruments of implementation for the first three targets. While Table 5 shows themes that are already represented by the existing targets, additional targets should be developed, encompassing new themes to capture interlinkages of SDG 7 with other SDGs. Capturing overarching changes will ensure these indicators track outcomes.

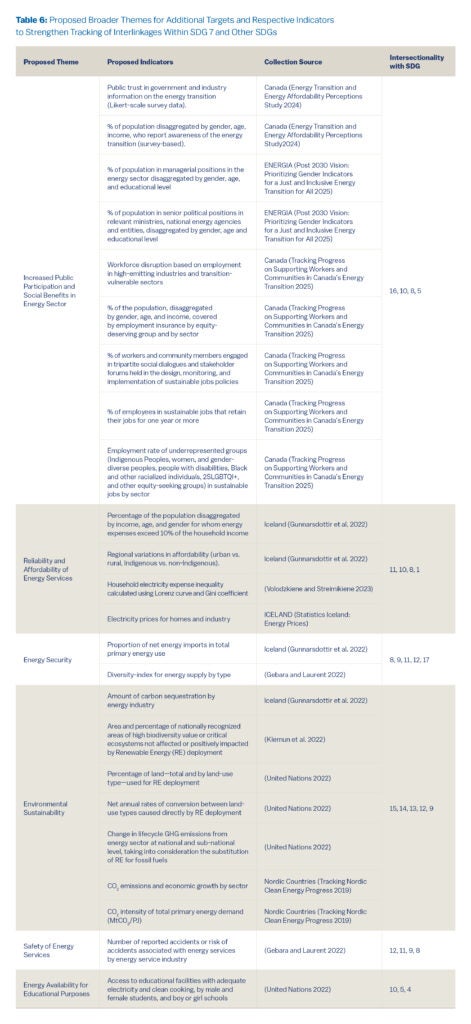

The Appendix (Table 6) outlines a broader set of proposed themes and indicators that could strengthen how progress on SDG 7 and its interlinkages are tracked. Examples already in use by champion nations include Canada’s survey data on public trust in energy transition policies and on employment outcomes for underrepresented groups in sustainable jobs, Iceland’s measures of energy affordability across income groups, and Nordic countries’ tracking of CO2 intensity in the energy sector.

For instance, measuring the share of women in managerial positions in the energy sector. While data collection methods exist in national contexts, most are not yet available globally for quick adoption into the SDG framework.

Summary and Conclusion

SDG 7 on Affordable and Clean Energy is central to achieving the 2030 Agenda, but its current indicators fall short in three ways: they lack demographic disaggregation, are not outcome-oriented, and weakly capture interlinkages with other SDGs. These shortcomings mean that while headline numbers show progress, they obscure who is being left behind, whether investments translate into tangible benefits, and how energy drives broader development priorities. Strengthening SDG 7 indicators post-2030 in the recommended ways will make them more equity-sensitive, outcome-focused, and interlinked with other goals.

While many of the proposed indicators can draw on existing datasets, global adoption remains constrained by inconsistent formats and uneven availability. Champion nations have piloted advanced methods for measuring equity and transition outcomes, yet these are not systematically collected worldwide. This gap calls for further research and stronger global collaboration to harmonize data collection.

Encouragingly, young researchers are increasingly contributing by deploying advanced tools such as GIS and remote sensing to reach regions that are otherwise hard to survey (Shahzad Javed et al. n.d.). However, scaling these efforts and embedding them into international reporting frameworks will require coordinated partnerships if the world wants to successfully incorporate equity-based, outcome-focused, intersectional datapoints post-2030.

Oindriza Reza Nodi

2025 Kleinman Energia FellowOindriza Reza Nodi is a Master of City Planning student concentrating in Smart Cities at the Weitzman School. Nodi is the 2025 Kleinman Energia Fellow.

ENERGIA. 2025. Post 2030 Vision: Prioritizing Gender Indicators for a Just and Inclusive Energy Transition for All [Slide show]. UN Commission on the Status of Women (NGO CSW69), March 21, 2025.

Fonseca, L. M., J.P. Domingues, and A.M. Dima. 2020. “Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability.” 12, no. 8, 3359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083359

International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). 2025. Tracking Progress on Supporting Workers and Communities in Canada’s Energy Transition. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2025-06/tracking-support-canada-energy-transition.pdf

Gebara, C., and A. Laurent. 2022. National SDG-7 “Performance Assessment to Support Achieving Sustainable Energy for All Within Planetary Limits.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 173, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112934

Gunnarsdottir, I., B. Davidsdottir, E. Worrell, and S. Sigurgeirsdottir. 2022. “Indicators for Sustainable Energy Development: An Icelandic Case Study.” Energy Policy, 164, 112926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112926

Hedera. n.d. Measuring Energy Access: The Multi-Tier Framework — HEDERA Case Study Portfolio. https://digital-report-portfolio-2021.hedera.online/about/mtf.html

International Energy Agency, International Renewable Energy Agency, United Nations Statistics Division, World Bank, World Health Organization, and Reyes, D. 2025. “Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report 2025.” Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/air-pollution-documents/air-quality-and-health/sdg7-report-2025.pdf?sfvrsn=863587e7_6&download=true

Junhua, L. SDG7 Policy Briefs in Support of the UN High-Level Political Forum 2025: Maximizing the Benefits of Energy Action for Good Health, Gender Equality and Decent Work to Leave No One Behind. Co-published by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway; Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, UK; ENERGIA International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy, Global Platform for Action (GPA), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark; Humanist Institute for Development Cooperation (HIVOS), The German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ); International Energy Agency (IEA); Ministry of Energy, Kenya; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands; Global Women’s Network for the Energy Transition (GWNET), Pakistan Mission to the United Nations; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Pakistan, International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UAE; PowerForAll, European Commission (EC). n.d. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2025_policy_briefs_in_support_of_the_high-level_political_forum-071525b.pdf

Klemun, M. M., S. Ojanperä, and A. Schweikert. 2022. “Toward Evaluating the Effect of Technology Choices on Linkages between Sustainable Development Goals.” iScience, 26, no. 2. 105727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105727

Matano, H. 2024. Clean Energy for Women, by Women. World Bank. March 16, 2024. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/clean-energy-women-women

Mulholland, E., A. Dimitrova, and M. Hametner. 2018. SDG Indicators and Monitoring: Systems and Processes at the Global, European, and National Level.” ESDN Quarterly Report, vol. 48. ESDN Office, Vienna. https://esdn.ixsol.at/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/QR_48_Final_Final.pdf

Natural Resources Canada. 2024. Energy Transition and Energy Affordability Perceptions Study. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2024/rncan-nrcan/M4-247-2024-eng.pdf

Nordic Energy Research. 2019. Tracking Nordic Clean Energy Progress 2019. https://pub.norden.org/nordicenergyresearch2025-01/nordicenergyresearch2025-01.pdf

Nordic Energy Research. 2025. Energy Efficiency in the Nordics. https://pub.norden.org/nordicenergyresearch2025-01/nordicenergyresearch2025-01.pdf

Parsons, J., C. Gokey, M. Thornton. 2013. Indicators of Inputs, Activities, Outputs, Outcomes, and Impacts in Security and Justice Programming. Vera Institute of Justice. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7eb9fae5274a2e87db1828/Indicators.pdf

Sustainable Energy for All | SEforALL. 2024. “Powering the Sustainable Development Goals.” March 27, 2024. Sustainable Energy for All. https://www.seforall.org/data-stories/powering-the-sustainable-development-goals

Shahzad Javed, M. J., Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, Norway, and Department of Technology Systems, University of Oslo, Norway. n.d. Engaging Young People for a More Inclusive National Energy Transition: A Participatory Modelling Framework. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2508.12352

Statistics Iceland. n.d. Energy Prices. https://statice.is/statistics/environment/energy/energy-prices

United Nations. n.d. “The Future We Want.” Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/futurewewant.html

———. 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/291/89/pdf/n1529189.pdf?token=exP5O3VFkmCQRzcTZw&fe=true

———. 2022. Policy Briefs in Support of the High-Level Political Forum Addressing Energy’s Interlinkages with Other SDGs. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/Policy%20Briefs%20-2022%20Energy%27s%20Interlinkages%20With%20Other%20SDGs.pdf

———. 2025. Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals the Gender Snapshot. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2025-09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2025-en.pdf

United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). 2026. High-Level Political Forum 2026. https://hlpf.un.org/2026

United Nations Statistics Division. n.d. IAEG-SDGs — SDG Indicators. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/disaggregation/

Volodzkiene, L., and D. Streimikiene. 2023. “Energy Inequality Indicators: A Comprehensive Review for Exploring Ways to Reduce Inequality.” Energies 16, no. 16: 6075. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16166075

Volodzkiene, L., and D. Streimikiene. 2025. “Integrating Energy Justice and Economic Realities through Insights on Energy Expenditures, Inequality, and Renewable Energy Attitudes.” Scientific Reports, no. 15: 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12410-y

World Bank, World Health Organization, International Energy Agency, International Renewable Energy Agency, United Nations Statistics Division, World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Program, and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2024. “Tracking Progress Toward SDG 7 Across Targets: Indicators and Data.” In Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report 2024, 141–143. https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/data/files/download-documents/SDG7%20-%20Report%202024%20-%20Chapter7-TrackProgTowardSDG7AccrTargets.pdf