Elevating Carbon Management: A Policy Decision-Making Framework and Rubric for the 21st Century

The digest outlines a 10-point policy framework to guide effective carbon management, emphasizing clear economic incentives, environmental safeguards, community engagement, and fossil fuel decoupling, using U.S. policy examples from 2025.

At A Glance

Key Challenge

Ensuring carbon management policies effectively decarbonize tough industries without prolonging fossil fuel reliance, harming communities, or burdening consumers with higher energy costs.

Policy Insight

Robust carbon management policy requires clear incentives, community engagement, stringent safeguards, and alignment with fossil fuel phase-out to ensure lasting climate and social benefits.

Introduction

In this digest, we specifically address policies supporting carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies, including overlapping carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods such as direct air capture (DAC) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). While broader categories of CDR exist—including marine CDR, nature-based, or agricultural solutions—we focus here on technological approaches with significant policy intersections with CCUS, aligning clearly with industrial decarbonization pathways.

Carbon management has emerged as a vital yet often contentious strategy for addressing climate change. While some see carbon management as essential for tackling hard-to-abate industries and removing legacy emissions, others fear it may prolong reliance on fossil fuels. At the same time, many national and subnational governments remain divided on how aggressively to pursue carbon management—especially when political priorities shift.

Considering Carbon Management Policies

When are policies supporting carbon management appropriate? This guiding question reflects a growing need to determine where, when, and how carbon management can best complement the broader clean energy transition. Achieving reliable, affordable clean energy systems—while also meeting long-term climate goals—will likely require a portfolio of solutions, including carbon management in specific contexts.

The Need for a Broader Lens

Given the complexity and interdependencies involved, carbon management must not simply focus on capturing and removing CO2 but also strategically align with broader societal and environmental goals.

- Real and permanent emissions reductions at scale through transitioning fully from unabated fossil fuel use.

- Protection of communities and the environment, providing tangible local economic and social benefits.

- Equitable economic development that includes cost and affordability considerations

This digest outlines a decision-making framework—referred to here as a “rubric”—to evaluate the effectiveness of carbon management policies in meeting these goals. We then examine the U.S. policy landscape at the start of 2025 to illustrate how applying this framework can highlight each policy’s strengths and weaknesses, reveal gaps, and clarify whether a basket of policies can collectively address core concerns. Notably, no single policy will fulfill every dimension; understanding how multiple measures fit together is key.

A Note on the Current Political Landscape: While recent shifts suggest a less supportive federal environment for carbon management, best-practice design principles remain crucial for states, companies, and future federal administrations. Even if carbon management slows under certain administrations, spelling out “what good looks like” ensures that policymakers, advocates, and investors have a roadmap for when and how to revive or expand carbon management initiatives responsibly. This framework explicitly considers policy feasibility, including dynamic aspects such as evolving technology costs, market maturity, and political viability.

The Decision-Making Framework (Rubric) for “Effective Carbon Management”

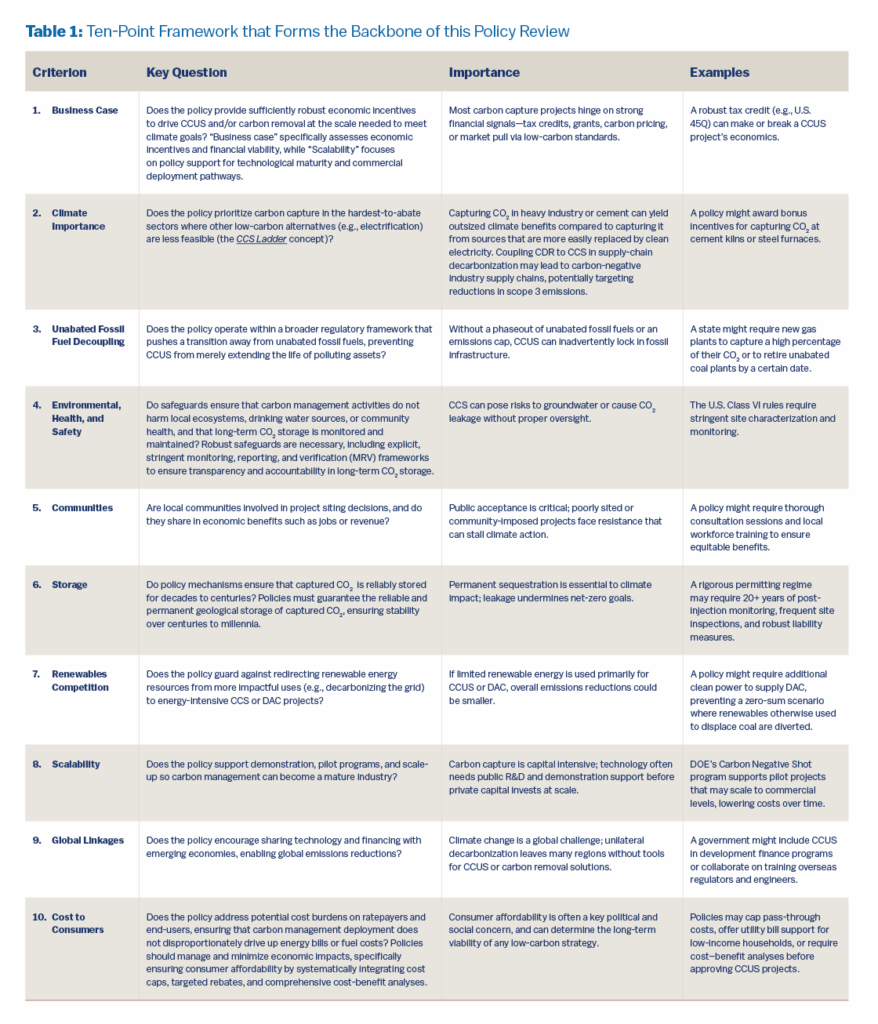

Below is a ten-point framework that forms the backbone of this policy review. The ten-point framework was developed based on the authors’ extensive experience in government, specifically their direct involvement in implementing major U.S. climate and energy policies, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and the Department of Energy’s Carbon Negative Shot initiative.

Each of the ten criteria supports one or more of the broader aims outlined above: transitioning fully from unabated fossil fuels, providing tangible community benefits, and promoting equitable economic development. While there is overlap (e.g., environmental, health, and safety can affect community acceptance), separating them helps ensure each dimension gets due consideration.

Scoring (1–4)

- 1 = Does not effectively address the criterion

- 2 = Somewhat addresses the criterion

- 3 = Addresses the criterion to a significant degree

- 4 = Addresses the criterion to a high degree

(A “4” is intentionally stringent, indicating the policy nearly fully meets best-practice standards. Policies that score lower on certain criteria may still be valuable but need targeted improvements.)

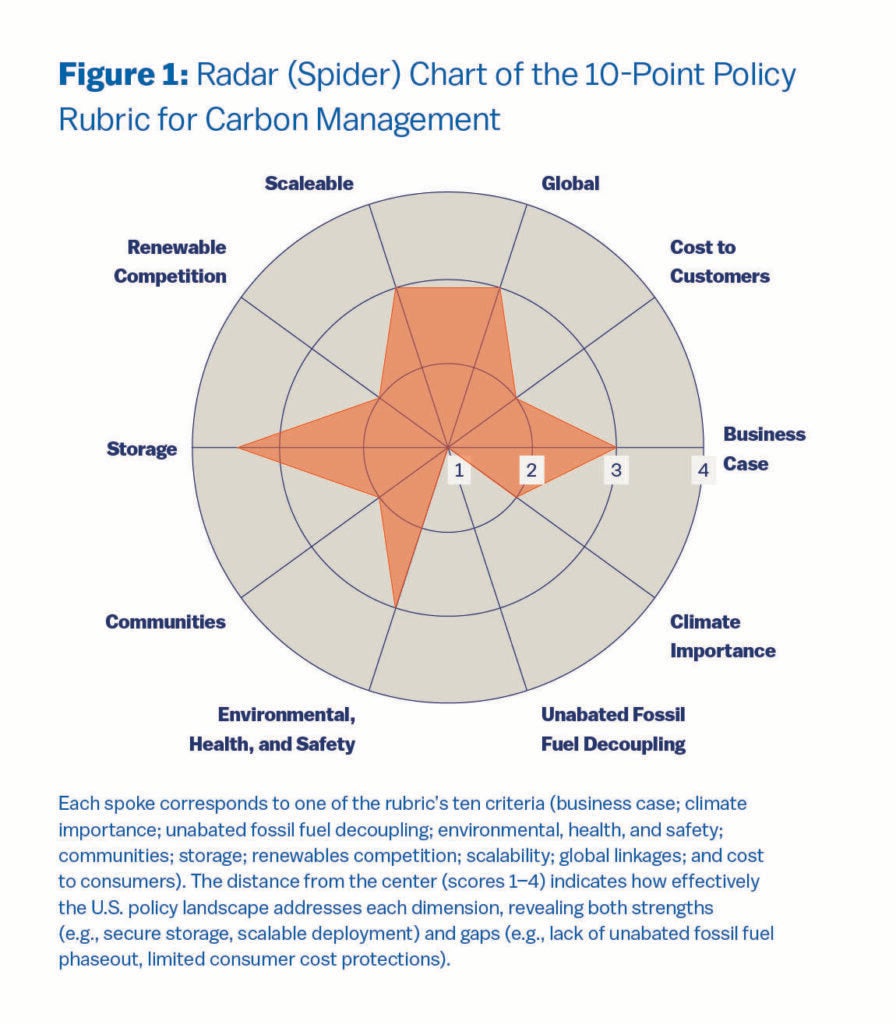

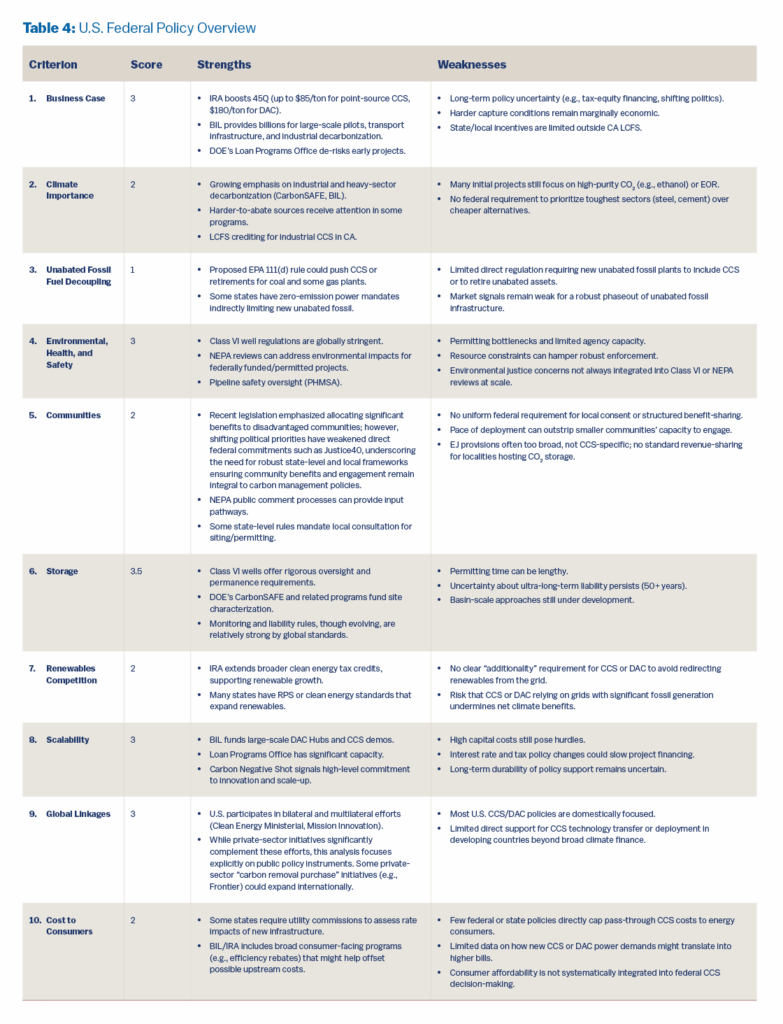

Radar (Spider) Chart of the 10-Point Policy Rubric for Carbon Management

Each spoke corresponds to one of the rubric’s ten criteria (business case; climate importance; unabated fossil fuel decoupling; environmental, health, and safety; communities; storage; renewables competition; scalability; global linkages; and cost to consumers). The distance from the center (scores 1–4) indicates how effectively the U.S. policy landscape addresses each dimension, revealing both strengths (e.g., secure storage, scalable deployment) and gaps (e.g., lack of unabated fossil fuel phaseout, limited consumer cost protections).

Why a “Framework” or “Rubric”?

Acknowledging the crucial concept of policy mixes that allow for different stakeholders to prioritize different elements of carbon management

- Financiers focus on economic feasibility (Criterion 1).

- Communities want local engagement and tangible benefits (Criterion 5).

- Consumers worry about potential bill increases (Criterion 10).

- Climate advocates emphasize secure storage (Criterion 6) and fossil fuel phaseout (Criterion 3).

By evaluating a basket of policies against these ten criteria—using a 1–4 scale—policymakers and stakeholders can see where the collective policy landscape is succeeding or falling short. Not every single policy will address all ten points, but a strong overall policy mix can ensure that carbon management aligns with 21st-century climate and equity goals.

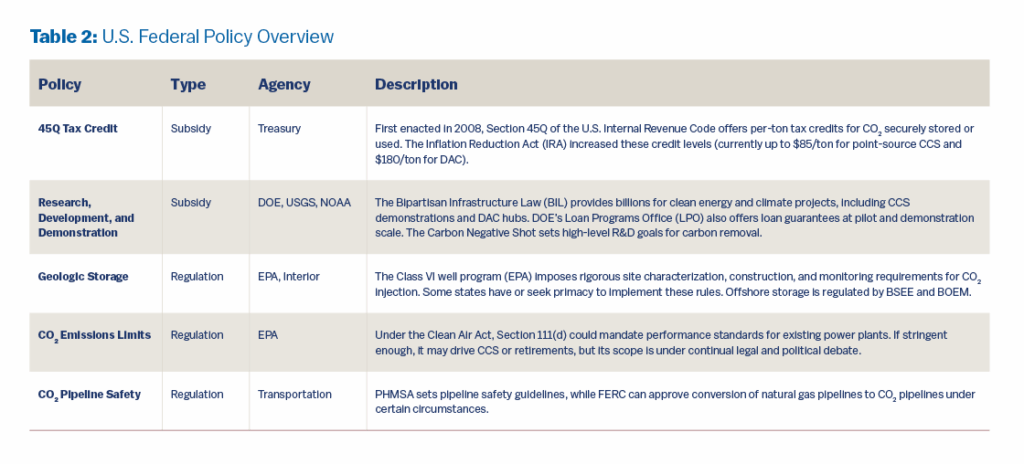

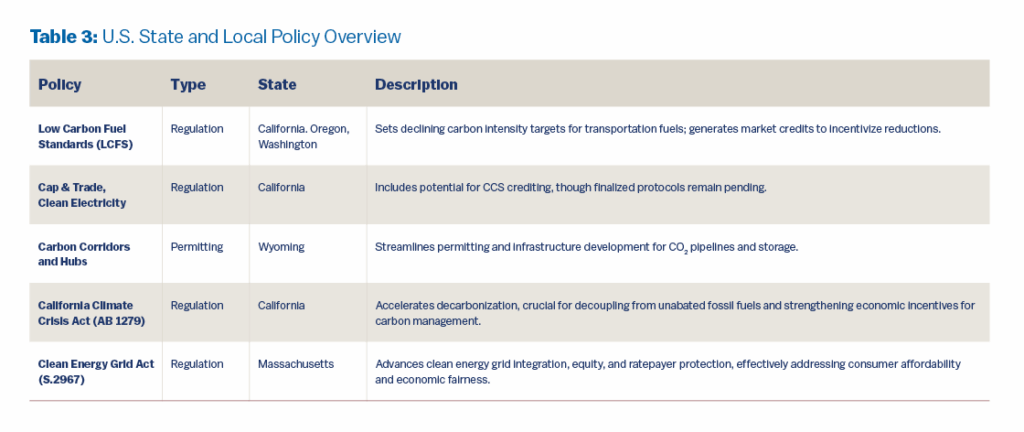

Case Study: U.S. – Overview of Key Policies

With this framework in hand, we turn to the U.S. policy landscape. While federal tax credits, infrastructure funding, and various state-level initiatives have evolved considerably, they still form a patchwork rather than a coherent, holistic approach. Below is a snapshot of major U.S. policies as of the beginning of 2025, followed by an analysis of how well they address each framework criterion as a collective.

Important Note on the “Unit of Analysis”

The policies below are often intended to work together—no single measure covers all aspects. The framework thus helps us see how the broader landscape stacks up, rather than judging any one program in isolation.

Applying the Framework: Grading the U.S. Carbon Management Policy Landscape

Overall, the U.S. policy landscape scores around 2.6 (on a 1–4 scale, 4 highest), reflecting significant strengths in certain areas (e.g., storage, scale-up) but notable gaps in others (e.g., fossil fuel decoupling, community input, and addressing consumer costs).

Below is a summarized scoring table, followed by detail on each criterion:

Opportunities for Improvement

Below are recommended ways to bolster U.S. carbon management policy for each criterion, with an eye toward both near-term feasibility and long-term best practices. These recommendations remain relevant regardless of the current federal stance; states, companies, and future administrations can adopt or adapt them.

- Business Case for Investment

- Extend and Expand 45Q: Provide a guaranteed multi-year extension with direct pay options (beyond the current five-year limit) and index credit values to inflation or cost of capital. Policy improvements must explicitly broaden beyond CCS, integrating diverse carbon removal technologies such as DAC, enhanced rock weathering, biochar, and others to comprehensively address climate goals.

- Leverage the Loan Programs Office: Streamline application processes and prioritize projects in truly hard-to-abate sectors (e.g., cement, steel).

- Enhance Predictability: Offer stable policy signals through 2030 and beyond, allowing developers and financiers to plan confidently.

- Align with the “CCS Ladder”

- Target Harder-to-Abate Sectors: Provide bonus 45Q or similar incentives for industrial emitters and cement/steel plants.

- Refine BIL/IRA Funding Criteria: Condition grants/loans on capturing CO2 from difficult processes rather than chasing “low-hanging fruit” with minimal additional climate benefit.

- Couple with Mandates and Regulations to End Unabated Fossils

- Strengthen EPA’s 111(d): Impose more stringent CO2 performance standards for coal and gas plants, prompting higher capture rates or retirements on unabated units.

- Regulate Industrial Emitters: Classify high-percentage CCS as a “best available control technology” for large stationary sources in steel, cement, refining, etc.

- Create Complementary Phaseouts: Gradually phase out CCS subsidies while ramping up zero-emission mandates, ensuring CCS is a bridge—not a crutch—on the path to a future without unabated fossil fuels.

- Environmental, Health, & Safety

- Expand Class VI Permitting Capacity: Increase agency staffing and resources to handle anticipated applications.

- Address Cumulative Impacts: Integrate stronger environmental justice guidelines into Class VI and NEPA reviews, ensuring that multiple CCS or DAC projects in one region don’t unduly burden local residents.

- Enhance Pipeline Safety: Update PHMSA regulations on CO2 pipelines and include community right-to-know provisions.

- Community Input and Socioeconomic Benefits

- Standardize Engagement: Make robust community consultations a requirement for federally funded CCS projects, with clear timelines and accessible technical assistance.

- Build Local Benefits: Incentivize local hiring and consider revenue-sharing mechanisms so communities hosting infrastructure directly benefit.

- Site with Consent: Strengthen or pilot “consent-based siting” processes.

- Increase Transparency: Ensure standard environmental impact assessments and data sharing.

- Long-Term Storage Security

- Scale Up CarbonSAFE: Fund comprehensive geologic site characterization across multiple basins.

- Improve Monitoring Technologies: Incorporate continuous measurement (satellites, sensors, etc.) to detect leaks.

- Clarify Liability: Ensure no gap exists in long-term stewardship or financial responsibility after site closure; explore private-public insurance models.

- Avoid Displacing Renewables

- Institute “Renewables Additionality”: Require CCS and DAC projects to source new, dedicated renewable capacity where feasible, rather than drawing from existing renewable resources that could otherwise directly decarbonize the grid. Robust ‘additionality’ provisions should explicitly demonstrate net climate benefits, ensuring carbon management complements renewables deployment rather than competes with it.

- Coordinate Grid Planning: Encourage grid operators (RTOs/ISOs) to plan for DAC/CCS loads, ensuring renewable capacity expands in tandem.

- Keep Clean Hydrogen Clean: If hydrogen is used for CCS power needs, mandate robust lifecycle standards (e.g., no “gray hydrogen” from unabated natural gas).

- Pathway to Commercial Scale

- Link BIL/IRA Funding with Offtake: Pair demonstration funding with guaranteed carbon-removal offtake (e.g., public procurement or private “Frontier” contracts), smoothing the path from pilot to market.

- Support FEED and Small Pilots: Maintain robust support for front-end engineering design, especially in emerging capture approaches.

- Coordinate Across Agencies: Align timelines among DOE, EPA, and other agencies so demonstration projects reach commercial operation without falling into policy gaps.

- International Equity and Technology Transfer

- Provide Development Finance: Leverage U.S. development finance (DFC, Export-Import Bank) to co-fund CCS in emerging economies where capital costs are prohibitive.

- Collaborate Mulilaterally: Expand open-access data and capacity-building (e.g., Class VI-like storage regulations) through forums like the Clean Energy Ministerial.

- Rework Global Markets: Allow U.S. carbon-removal purchase agreements to include international projects, fostering technology diffusion and equitable deployment.

- Cost to Consumers

- Utility Bill Protections: Develop regulations that cap or spread out costs for CCS retrofits to prevent rate shock, especially in regulated electricity markets.

- Transparent Cost-Benefit Analyses: Require regulators to publish rigorous consumer impact assessments before approving new CCS or DAC projects tied to utility ratepayers.

- Provide Targeted Relief: For low- and moderate-income households, expand energy bill assistance or efficiency programs, ensuring that decarbonization efforts do not exacerbate energy poverty.

Conclusion

As assessed at the beginning of 2025, the U.S. carbon management policy landscape demonstrates notable progress—particularly through the Inflation Reduction Act’s expanded 45Q credits, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s demonstration funding, and ongoing Department of Energy R&D initiatives. However, substantial gaps persist and could widen if not promptly addressed, particularly in ensuring that carbon management:

- Genuinely targets hardest-to-abate emissions,

- Operates alongside a clearly defined phaseout of unabated fossil fuels,

- Incorporates rigorous community engagement and environmental justice considerations,

- Explicitly safeguards consumer affordability.

Political realities often shift the feasibility and momentum behind federal carbon management policies, underscoring the essential role of state, local, and private-sector leadership. Clearly defining and consistently upholding best-practice standards ensures readiness for when federal priorities realign. Even during periods of reduced federal enthusiasm, establishing and maintaining robust frameworks and transparent definitions provide the necessary groundwork for swift, responsible policy action.

Ultimately, well-designed carbon management strategies are not about prolonging fossil fuel dependence. Rather, they responsibly deploy critical tools within a diversified portfolio of climate solutions—solutions aimed squarely at stabilizing our climate, safeguarding communities, and advancing an equitable and resilient low-carbon future.

Jennifer Wilcox

Presidential Distinguished ProfessorJen Wilcox is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering and Energy Policy. She previously served as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the Department of Energy.

Noah Deich

Senior FellowNoah Deich is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center. He recently left the Biden Administration, where he served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Carbon Management at the Department of Energy.

Holly Jean Buck

Associate Professor, University of BuffaloHolly Jean Buck is an associate professor in the Department of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Buffalo. Her research focuses on climate change and environmental policy and public participation in emerging technologies.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management – “Carbon Negative Shot.”

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) updates on CO₂ pipeline safety.

- State-level Low Carbon Fuel Standards (California Air Resources Board, Oregon DEQ, Washington Dept. of Ecology).