Closing the Climate Finance Gap: A Proposal for a New Green Investment Protocol

While international legal agreements protecting foreign investment are much criticized for standing in the way of government efforts to address climate change, these same agreements—if properly deployed—can help close the climate finance gap.

At a Glance

Key Challenge

How can the climate finance gap be closed by using the tools and incentives of international law to incentivize private climate finance flows?

Policy Insight

A new multilateral investment protection agreement under the auspices of the UNFCCC expressly designed to facilitate cross-border climate finance flows.

Executive Summary

International legal agreements protecting foreign investment are much criticized for standing in the way of governments regulating to address climate change, but in fact, investment law must be a core pillar of climate finance and, particularly, derisking private climate finance flows. To do so requires linking the international legal regimes governing investment and climate.

This report examines the interplay of the international legal protection of foreign investment and the global effort to finance climate adaptation and mitigation, concluding that international investment law can be a potent tool to incentivize cross-border private climate finance flows.

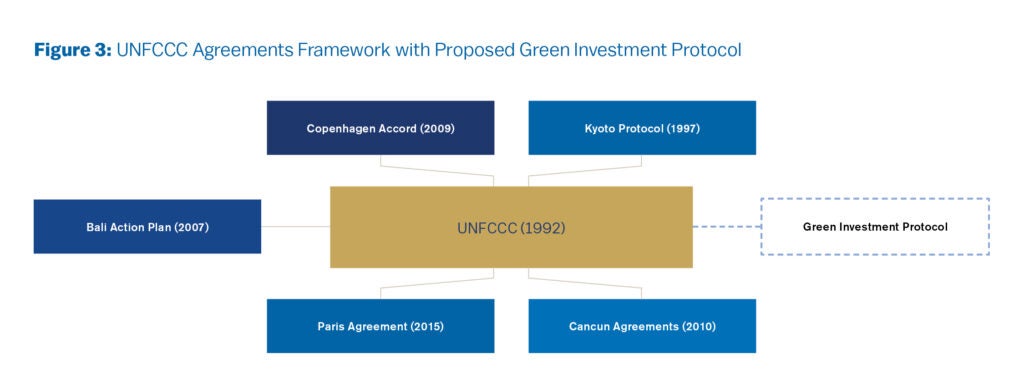

To achieve that goal, the digest proposes the development of a Green Investment Protocol (GIP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that offers modified legal protection of climate-friendly cross-border private direct investment. This new agreement would expressly link the legal regimes governing climate and investment, reducing the risks associated with private climate finance, particularly to developing countries, while mitigating the liabilities they might otherwise face for climate-friendly regulatory action.

Introduction

Despite the potential of international investment agreements (IIAs) to de-risk and thereby incentivize needed private finance flows, current policy debates and proposals have largely focused on curtailing—rather than expanding—international investment protections. IIAs are binding international treaties through which states commit to protect foreign direct investments (FDI) against various forms of regulatory interference and provide direct rights of legal action to foreign investors should such violations occur.

These agreements were originally intended to facilitate FDI flows, particularly to developing countries with less certain domestic legal regimes. More recently, however, IIAs have been fiercely criticized for hindering state regulatory actions that advance Paris Agreement climate mitigation and adaptation obligations.

Referencing the “perverse” nature of legal treaties protecting foreign investments that have allowed fossil fuel companies to secure arbitral awards totaling six times the available pledges in the Green Climate Fund, former Irish President and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson has called for a rethinking of investment law (Robinson, 2024).

Such an agenda would, first, expressly link the legal protection of foreign direct investment with existing international climate law. Second, it would address Robinson’s concerns by deploying existent legal mechanisms to limit state liability for regulatory actions that advance Paris goals. Third, it would offer new and expanded legal protections for green cross-border private climate finance flows.

This report lays out the case for reorienting international investment law to align with and support international climate law. It offers a sketch of how a positive agenda for investment law could preserve state freedom of action to regulate in ways that advance climate commitments.

Simultaneously, the agenda deploys the risk-mitigating power of investment’s legal protection to advance climate-friendly—and only climate-friendly—private financial flows by expressly linking the legal regime governing foreign investment protection with international climate law. To do so, this digest proposes a new protocol to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that aligns states’ investment protection obligations with climate regimes and increases the scope of climate-friendly legal protections for green investments that could help close the climate finance gap.

Backlash Against Foreign Investment Protection

A powerful critique of investment protection law is based on an emerging trend of international arbitral tribunals ordering governments to compensate fossil fuel producers for regulatory action that advances Paris climate commitments. Investment law thereby either increases the cost of meeting Paris goals or incentivizes states not to take necessary regulatory actions. One estimate suggests that the potential investment law liability for the phase-out of upstream oil and gas alone could reach $340 billion (Tienhaara et al. 2022).

As a point of comparison, that figure exceeds the $321 billion in total public climate finance globally in 2020 (Ibid). Additionally, the total cost of investor liability for wholistic fossil fuel phase-out has yet to be estimated, though it would be significantly higher if the $276 billion invested in coal plants were also considered (Tienhaara and Cotula 2020, 25).

Two examples are illustrative. A German investor in the Dutch coal sector brought an investment law claim against the Netherlands after the government implemented regulations prohibiting coal fueled electricity by 2030. (RWE v. Netherlands 2021). The investor claimed the Dutch regulations breached the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), an international legal agreement protecting foreign investments in the energy sector. A similar claim was brought by Rockhopper, a U.K. company that invested in the Italian coal sector, leading to an investment tribunal’s order for Italy to compensate Rockhopper 184 million EUR (IISD and Wu 2023).

Such large financial awards have prompted calls for states to exit international investment protection agreements. The ECT has been a particular focus of criticism (Bloxenheim 2023; Furbank 2022). The U.N. Special Rapporteur on Climate Change and Human Rights most recently recommended repealing the ECT, discussing the fossil fuel producers’ use of the “Investor-State dispute settlements within the [Treaty] to sue States for compensation if they take positive policy actions to reduce the use of fossil fuels,” (UNGA 2022).

Many governments, including EU member states collectively, have announced their intent to withdraw from the treaty in its entirety (IISD 2022; European Parliament 2024). More broadly, a range of states are either terminating their bilateral investment treaties (BITs) or have exited from the treaty establishing the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), where investment claims are often arbitrated (Johnson et al. 2018).

Simultaneously, some countries are replacing the traditional legal protections for foreign investment with a new style of agreement that focuses instead on investment facilitation. Unlike traditional investment treaties, investment facilitation agreements do not provide investors with the right to bring direct legal claims against states that interfere with their investments. Instead, they, along with some existing BITs, offer only state-to-state arbitration to resolve any disputes that may arise.

The first such investment facilitation agreement, the Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement between the EU and Angola (SIFA), was approved by the Council of Europe in early 2024 (European Council 2024). While SIFA seeks to incentivize cross-border investments, it does not provide the full suite of investment protections, including expropriation, national treatment, fair and equitable treatment, or full protection and security (Angola and EU 2024). While agreements such as SIFA may avoid potential state liability for climate friendly regulation, they do sacrifice the risk mitigation effect of investor-state dispute settlement and, therefore, have a far more limited ability to incentivize cross-border financial flows.

Closing the Climate Finance Gap

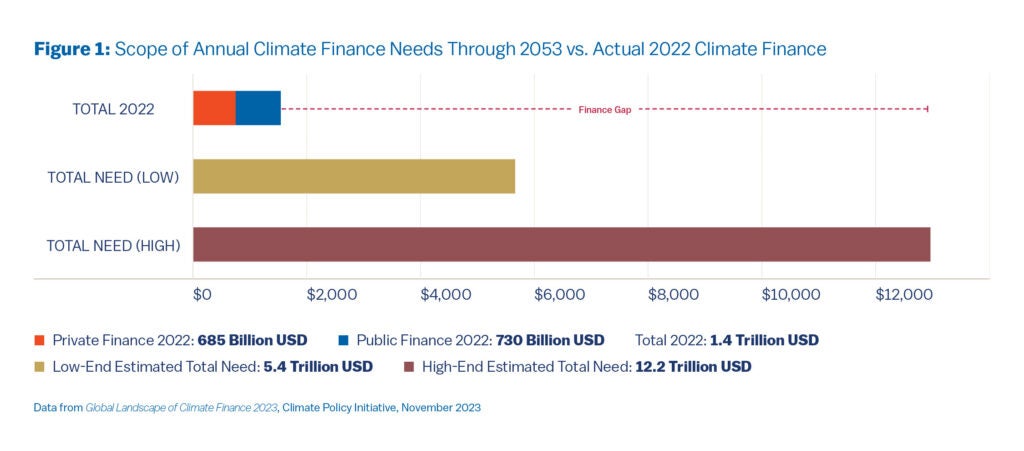

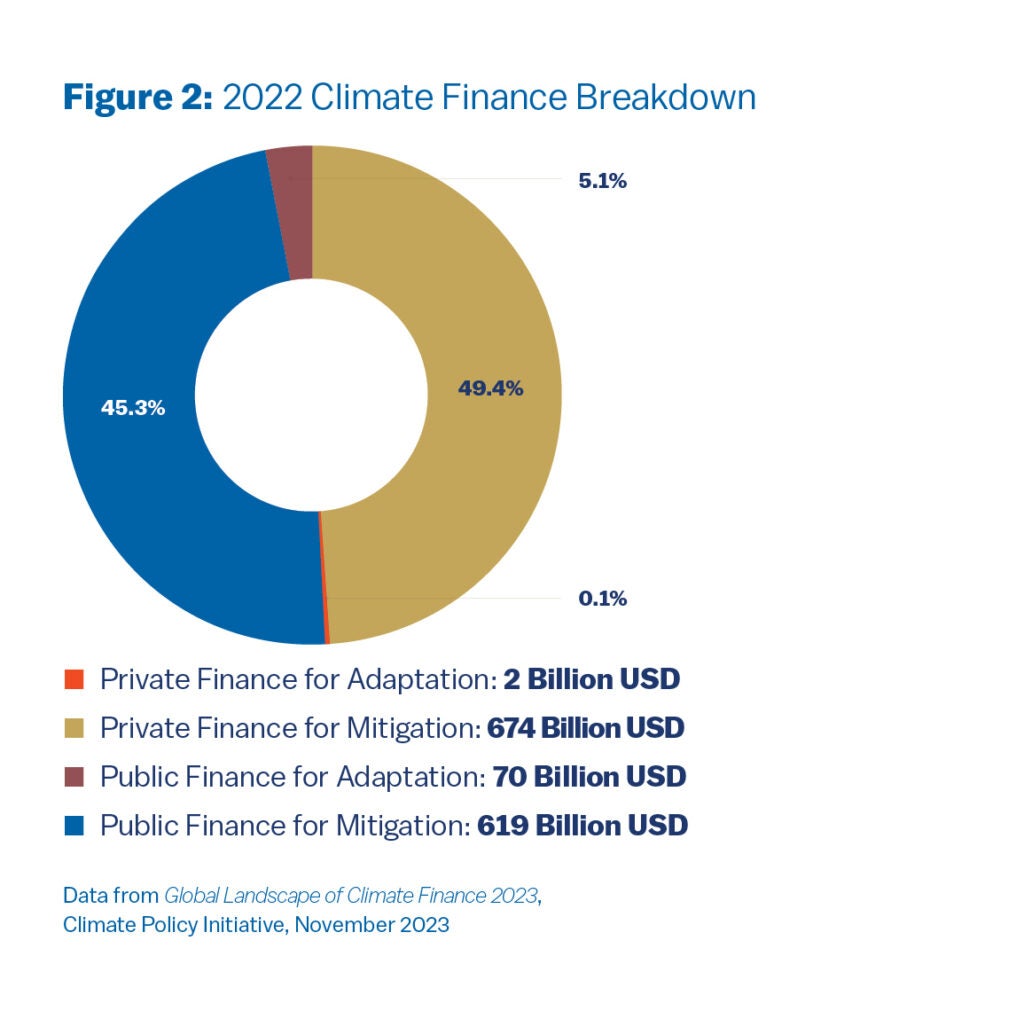

This backlash against the protection of foreign direct investment coincides with an urgent and growing need for foreign direct investment in climate adaptation and mitigation. While estimates vary widely, it has become clear that the cost of climate adaptation and mitigation will be extraordinary, and estimates continue to increase. For example, mitigation finance needs are expected to surpass $8.4 trillion USD per year between now and 2030, whereas the current financial flows geared toward mitigation were only $1.2 trillion USD in 2021-2022 (Buchner et al. 2023). For adaptation, the estimated collective finance required for developing countries alone is between $130-415 billion USD per year between now and 2030 (GCA 2023), compared to the current financial flows of $63 billion USD in 2021-2022 (Buchner et al. 2023). These figures likely underestimate the actual scale of capital needed, particularly with respect to adaptation.

Perhaps the single most important question for climate action is where the necessary financial resources to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate will come from. In short, how can we close the climate finance gap? Public sector financial flows, particularly to and within developing countries, are woefully inadequate. It was only in 2022 that developed countries finally met their pledge made in Copenhagen in 2009 to mobilize $100 billion per year in climate finance for developing countries (OECD 2024).

The total public climate finance, including within developed states in 2022 was a mere $619 billion USD, far short of the total need (Buchner et al. 2023). To close this climate finance gap, private sources of capital must radically increase in the years ahead (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2023, 9). While trend lines have been moving in the right direction for the past several years (CPI 2021, 12), increasing the scale of private climate finance flows by several orders of magnitude over the next decade will not be an easy task (Pauw et al. 2022).

As a theoretical matter, IIAs should incentivize private cross-border investment flows. IIAs are based on legal guarantees by the host states of foreign investments that they will treat such investments fairly, including a prohibition on expropriation, a commitment to accord such investments fair and equitable treatment, and guarantees that benefits offered to investors of one state will be accorded to all covered investments.

Critically, most investment agreements provide investors with a direct remedy in cases of violation—namely, the ability to directly bring a claim against the host state before an international investment tribunal, often under the auspices of the World Bank (Kaufmann-Kohler and Potestà 2020, 13). These legal protections and, particularly, the right of remedy, give investors security against many political and regulatory risks, thereby reducing the risk-premium associated with and cost of foreign capital (Egger, Pirotte, and Titi 2023).

The empirical evidence to back this theoretical claim is, admittedly, mixed, often showing “diverse and, at times, contradictory results.” (Pohl 2018, 28). Despite a very large literature on the topic, studies have, at best, been able to prove a modest correlation between investment protection agreements and increased FDI flows (Brada, Drabek, Iwasaki 2021). Some academic literature describes a “positive and statistically significant” correlation between the existence of strong investment protection with increased FDI flows and a decreased cost of capital (Egger and Pfaffermayer 2004) but has been unable to prove causation (Bonnitcha et al. 2017, 159).

Other studies find more limited, if any, correlation between IIAs and FDI flows (Webb 2008). These challenges are likely rooted in both data-collection and conceptual problems that have limited the effectiveness of empirical studies (Kaufmann-Kohler and Potestà 2020, 16-17) and are beyond the scope of this policy brief to resolve. Theoretical reasoning, however, suggests that if IIAs can de-risk and thereby promote FDI flows, those effects will likely be greatest with respect to large, long-term investments (such as in the green energy sector) at the time of the establishment of such investments given the significant financial benefits of Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS).

Given the urgency of climate action and the extraordinary need for climate finance, every potential mechanism to stimulate and incentivize climate-friendly investment must be deployed. Particularly since legal mechanisms have been developed to address many of the justifiable concerns about legacy investment agreements such that the de-risking effect of IIAs can be realized while still preserving state freedom of climate-related regulatory action, the costs of bringing the power of IIAs to bear on climate finance can be minimized (Gehring, Segger, and Hepburn 2012, 101; Marshall 2010, 73).

The challenge—and the opportunity—is to develop new substantive terms for IIAs that harness the de-risking benefits of legal protection for cross-border climate finance, whatever their extent, without generating potential liability for governments that advance climate-positive regulatory action.

Regime Linkage

A first step in developing a climate-positive role for international investment law is to expressly link the international legal regimes governing climate and investment. To date, the international legal architecture designed to address climate change has never expressly engaged international investment law, nor have IIAs been recognized as a part of international climate law (Martini 2024, 5). International investment law developed through a network of bilateral agreements focused on the protection of foreign investors, beginning with the first bilateral investment treaty in 1959 and now comprising more than 3,000 such agreements and several key regional agreements (Egger, Pirotte, and Titi 2023).

In contrast, international climate law developed through a multilateral process beginning with the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment in 1972 and leading to the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, and the 2016 Paris Agreement. As the two regimes have developed, they have never reconciled their evolving substantive content nor found ways to harness their areas of mutual compatibility. Exemplary of this, amongst the 2,592 IIAs in the UNCTAD IIA mapping project database, only 163 contain mention of “climate,” 22 mention the UNFCCC, and 13 mention the Paris Agreement.1

The separation between these two legal regimes is a root cause of the investment awards that hold states liable for climate-friendly regulation. International arbitrators adjudicating investment disputes often see the dispute entirely through the lens of investment protection, without sufficient attention to the state’s other legal obligations, including climate obligations. One recent study found that of 64 investment awards related to states’ climate policies, none “discussed climate change in any substance.” While 13 awards mention the phrase “climate change” and 12 give cursory mention to the UNFCCC, international climate law has never had a dispositive impact on the outcome of an investment tribunal (Ipp, Magnusson, and Kjellgren 2022, 32-33).2 Emblematic of this divide, when the Italian government’s renewable energy scheme was challenged before an investment tribunal, the tribunal found the scheme’s environmental goals to be “irrelevant” and held that “liability questions […] need only be determined through an application of the ECT itself” (ESPF Beteiligungs and InfraClass Energie v. Italy, paras. 401, 402).

The Conference of Parties (COP) of the UNFCCC has failed to recognize the potential of international investment law to incentivize climate finance. My review of the decision texts of all 28 annual COPs found no direct references to international investment law or investment treaties. Similarly, our review of the workflow of the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance (SCF) shows that the SCF has never had international legal protection of foreign investment on its agenda, despite considering a range of other de-risking mechanisms to facilitate investment flows. Only as of 2024 has the issue of investment treaties been added to the Sharm-el-Sheik Dialogue on Article 2(1)(c) of the Paris Agreement, where it remains at the periphery of the work of the COP (Tienhaara 2024).

Ultimately, an integration of investment law and climate law must start with engagement from both sides. Tribunals arbitrating investment cases must move toward an interoperative dialogue that considers both investment and climate law. Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties gives tribunals the authority, and arguably the obligation, to take into account “any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties.” In so doing, tribunals could “move from what often appears to be a myopic vision of the international legal system that foregrounds investment obligations over potentially competing obligations toward” a balancing of competing legal obligations (Burke-White 2015, 5). From the climate side, the COP must recognize the role of investment law in climate finance and have input into the future climate-compatible evolution of investment law.

A second step toward this integration of investment and climate law involves substantive changes to IIAs to ensure they do not hinder states’ abilities to meet climate goals, without undermining their ability to incentivize FDI flows. Over the past several decades, experimentation by national governments in their bilateral investment agreements has yielded several legal innovations to avoid potential liability for non-discriminatory regulation.

First, the preambles of investment agreements, which often provide an important context to guide tribunals’ interpretation of investment commitments, should expressly reference climate change goals. For example, the preamble to the 2019 Myanmar-Singapore BIT reaffirms the countries’ rights to enact “environmental measures relating to investments in their territories in order to meet legitimate public policy objectives” (Myanmar and Singapore 2019).

Second, states can incorporate non-precluded measures provisions into their investment treaties that exempt certain categories of state conduct from investment protections. For example, the China–Mauritius FTA includes NPM language precluding the treaty from being construed “to prevent a Party from adopting or maintaining […] environmental measures” (China and Mauritius 2019, Art. 8.9(d)).

Third, states can include denial of benefits clauses that deprive corporations that fail to comply with a state’s climate laws from protection under the treaty. For example, the 2019 Dutch Model BIT requires the tribunal to decline jurisdiction if the investor fails to comply with the state’s “environmental protection and labor laws” (Kingdom of the Netherlands 2019, Art. 7(1)).

Finally, legitimate and non-discriminatory regulatory action that advances climate goals “should be excluded from the scope of treaty protection against expropriation through expressly tailored climate carve-outs (Paine and Sheargold 2023). The 2019 India–Kyrgyzstan BIT provides that “nondiscriminatory regulatory measures” which protect “legitimate public purpose objectives such as … the environment shall not constitute” expropriation (Kyrgyzstan and India 2019, Art. 5(5)).

The reform of the content of IIAs in this climate-friendly direction must be based on three core principles. First, it must involve a mutual dialogue, with the COP helping guide and shape the reform of investment agreements and states drafting investment agreements remaining acutely aware of the interactions between the two legal regimes. Second, the reform of investment law must be both prospective and retrospective, aligning the content of new investment agreements with international climate goals and revising the content of existing agreements to reflect these goals. Finally, reforms must not undercut the substantive protections of investment law or remove the investors’ right to arbitrate such that the de-risking role of investment law is preserved.

An Investment Protocol to the UNFCCC

While such ad hoc linkages between climate law and investment law would be a step in the right direction, the actual integration of the two legal regimes requires a new Green Investment Protocol (GIP) to the UNFCCC. The GIP would be a multilateral investment protection agreement under the auspices of the UNFCCC expressly designed to facilitate cross-border climate finance. Structurally, the GIP would be designed as a protocol to the UNFCCC, open to any member state of the COP, like the Kyoto Protocol or the Marrakesh Accords as provided for in Article 17 of the UNFCCC (Climate Change Secretariat 2006, 71-73).

Substantively, to maximize the de-risking effects of investment protection agreements, the GIP would include the traditional standards of treatment for foreign direct investment found in most existing IIAs, including expropriation, national treatment, most favored nation treatment, minimum standard of treatment, and full protection and security. Likewise, it would retain traditional rights for investors to bring claims against host states before international investment tribunals under the auspices of the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), UNCITRAL arbitration, or both. These protections lie at the core of investment law and are indispensable to reducing the risks associated with cross-border financial flows.

The GIP would, however, innovate beyond traditional IIAs and actively align investment and climate law in several dimensions. First, and most significantly, the GIP would condition investment protection on the alignment of particular investments with climate finance goals. An international pre-screening mechanism would determine whether a particular proposed investment advances climate adaptation and mitigation agendas and would qualify for legal protections. As a starting point, GIP protections could be limited only to investments co-financed by one of the UNFCCC’s climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), and the Adaptation Fund (AF).

Investments that were, in part, financed through UNFCCC funding mechanisms would already have a strong climate-friendly stamp of approval. Admittedly, some states, particularly in Europe, might be concerned about associating UN climate funds with the ISDS regime. However, the proposed GIP offers a radical departure from existing—and problematic—approaches to investment protection and, as discussed below, creates a mechanism to limit state liability under existing investment agreements.

The prescreening process could be expanded to include projects supported in part by the World Bank or regional development banks or projects that are insured in part by the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). Co-financed projects represent only a sliver of total green FDI flows3, and mechanisms would need to be developed to broaden the scope of protected green investments. To do so, operational definitions of green investment would need to be developed, perhaps building on those included in the Investment Plan for Europe, the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation, and the European Commission’s Global Green Bond Initiative. Alternatively, a sub-committee within the SCF could review investment proposals to determine their suitability for legal protection.

Second, the GIP could be structured as the exclusive investment protection remedy available to investors. Some states find themselves saddled with legacy IIAs that they perceive went too far in protecting investments at the expense of states’ abilities to regulate in the public interest. The GIP offers a partial solution through a variation on a “fork-in-the-road” provision (Petsch 2019). When a potential investor seeks public financing from a UNFCCC climate fund, the investor could be required to relinquish rights to any remedies under legacy BITs as a condition precedent to receiving public financing and protections under the GIP. For maximum effectiveness, shareholders and creditors would also need to waive claims under legacy treaties, particularly as relates to reflective loss. (Arato, 2019). While investors would retain protection under the GIP, the fork-in-the-road would reduce potential state liability under less-climate-friendly legacy IIAs. This legal structure alone could be extremely attractive to states critical of the present investment protection regime and could generate significant political support for the GIP.

Third, the GIP would include all the best practices that have emerged for effectively balancing the protection of investments with states’ rights to regulate in furtherance of their climate objectives. Drawing on recent innovations in the design of IIAs, such as the 2019 Netherlands Model BIT and the Canada–EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, the GIP would include the range of balancing mechanisms discussed in Part IV. These would include non-precluded measures provisions limiting state responsibility for climate-related regulations, denial of benefits clauses for investors who violate host or home state environmental regulations, and a clear articulation of states’ rights to regulate climate issues.

The most favored nations clause in the GIP would be narrowly drawn to preclude its application in a way that would undercut these legal innovations. To further reduce the barriers to climate-favorable investment the GIP could also include the investment facilitation benefits found in SIFA. Admittedly, the negotiation of the terms of what is effectively an updated multilateral treaty on investment would be challenging, as evidenced by the difficulty in securing agreement, even among like-minded states, on updates to existing bilateral agreements. The potential benefits of a GIP, both for the future coherence of investment law and for closing the climate finance gap, make that a worthwhile effort at the very least.

Fourth, the GIP would allow expanded coverage of green investments, including between states that currently lack IIA protections. While there are more than 3,000 bilateral investment treaties in place today (Egger, Pirotte, and Titi 2023), many country dyads, including the U.S.–China dyad, remain uncovered, despite more than $150 billion in annual FDI flows in 2022 (Statista 2023)4 The GIP would help close these gaps and reduce the concerns of countries that have been reluctant to enter new IIAs by limiting legal protections to climate aligned FDI and including provisions to preserve state freedom of non-discriminatory regulation.

Fifth, and perhaps most radically, if concerns persist, even under the GIP, about developing country liability for climate-friendly regulatory actions, the GIP could include an indemnification mechanism for certain countries and with respect to a limited set of treaty breaches. More specifically, the GIP could indemnify least developed countries and states most at risk from climate change for any non-discriminatory regulatory actions needed to facilitate their adaptation or mitigation efforts and undertaken consistent with the due process of law. The substantive protections included in the GIP would continue to reduce the risks associated with investments in such states, but the indemnification mechanism would shift liability for non-discriminatory regulation from the LDC to an international finance pool.

This proposed indemnification mechanism would differ from typical risk insurance, for example, that provided by MIGA, as host states would still face potential liability for more egregious behavior or regulatory action not related to a Paris climate objective. Limiting indemnification to non-discriminatory regulatory actions undertaken to advance an LDC’s Paris Agreement climate goal would continue to incentivize host states to regulate consistent with due process requirements but would shield them from unexpected liabilities.

To provide such indemnification, an international finance pool could be established, consistent with the principles of common but differentiated responsibility. Admittedly, the prospect of an international climate finance mechanism compensating investors for regulatory harms by host states may be a political stretch, but it might be necessary to minimize the risks of cross-border private climate finance to LDCs, while minimizing the risks of liability for those countries.

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that international climate law and international investment law have evolved separately over the past decades, creating unnecessary tensions between two potentially synergistic international legal regimes. The current backlash against international investment protections in the name of advancing climate action would undermine one of the few available tools to help close the climate finance gap. The international legal protection of foreign investment admittedly has its problems. But the solution is not to walk away from its potential to de-risk private climate finance flows. Rather, a deep integration of international investment law and international climate law is urgently needed to align these bodies of law with the goals of climate mitigation and adaptation.

Such an alignment could begin with incremental changes to update IIAs and to generate dialogue between the institutions of investment law and climate law. To fully harness the power of investment protection law to close the climate finance gap, however, requires a bold vision for a new multilateral investment agreement expressly designed to protect climate-friendly investments and facilitate needed private finance flows, particularly to LDCs.

In fact, a green investment protocol to the UNFCCC would go far to fulfill the obligations of states under the Paris Agreement to “make finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.” Through the COP, developed country parties could “take the lead in mobilizing climate finance from a wide variety of sources” through an investment protection protocol. The costs of a well-designed investment protocol would be very low, and the benefits potentially significant, both to mitigating concerns about the impact of legacy IIAs on states’ climate regulations and to incentivizing the flow of climate finance to the countries that need it most.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Sienna Colburn, Alara Hanci, and Paul-Angelo dell’Isola for invaluable research assistance and Lauge Poulsen for feedback and guidance on earlier drafts. The author is grateful to the OECD for the opportunity to present an earlier version of this proposal at the 9th OECD Investment Treaty Conference.

William Burke-White

Professor of Law, Carey Law SchoolWilliam Burke-White is Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School. Burke-White, an international lawyer and political scientist, is a leading expert on U.S. foreign policy, multilateral institutions, and international law.

Arato, Julian. 2019. “Private Law Critique of International Investment Law,” 113 American Journal of International Law 1 (2019).

Angola, European Union. 2024. “Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement Between the European Union and the Republic of Angola.” EUR-Lex. Document 22024A00830. Vol. ISSN 1977-0677. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/agree/2024/830/oj.

Bloxenheim, Henry. 2023. “The Energy Charter Treaty: Reform or Retreat?” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. January 16, 2023. https://www.jtl.columbia.edu/bulletin-blog/the-energy-charter-treaty-reform-or-retreat.

Bonnitcha, Jonathan, Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen, and Michael Waibel. 2017. The Political Economy of the Investment Treaty Regime. Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780198719540.

Brada, Josef C., Zdenek Drabek, and Ichiro Iwasaki. 2021. “Does Investor Protection Increase Foreign Direct Investment? A Meta‐Analysis.” Journal of Economic Surveys 35.1 (2021): 34-70.

Buchner, Barbara, Baysa Naran, Rajashree Padmanabhi, Sean Stout, Costanza Strinati, Dharshan Wignarajah, Gaoyi Miao, Jake Connolly, and Nikita Marini. 2023. “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023.” Climate Policy Initiative. November 2, 2023. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2023/.

Burke-White, William. 2015. “Inter-Relationships Between the Investment Law and Other International Legal Regimes.” E15 Initiative. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) and World Economic Forum. https://sustainableocean.sites.uu.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/276/2019/01/E15-Investment-Burke-White-Final.pdf.

Canada and European Union. 2016. “The Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement.” https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/canada/eu-canada-agreement/ceta-chapter-chapter_en

China and Mauritius. 2019. “Free Trade Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of Mauritius and the Government of the People’s Republic of China.” https://www.mcci.org/media/278863/doc-1-mauritius-china-fta-text.pdf.

Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC). 2006. “Chapter 10: Adopting Protocols.” UN Framework Convention on Climate Change: Handbook, ISBN: 92-9219-031-8. Bonn, Germany: Produced by Intergovernmental and Legal Affairs, Climate Change Secretariat. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/publications/handbook.pdf.

Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). 2021. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Full-report-Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance-2021.pdf.

Council of the European Union. 2020. “European Parliament, Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, Regulation.” Document 32020R0852, adopted June 18, 2020. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/852/oj.

Council of the European Union. 2022. “Investment Plan for Europe.” European Council. August 10, 2022. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/investment-plan/.

Council of the European Union. 2023. “European Green Bonds: Council Adopts New Regulation to Promote Sustainable Finance.” Press release. October 24, 2023. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/10/24/european-green-bonds-council-adopts-new-regulation-to-promote-sustainable-finance/.

Egger, Peter, Alain Pirotte, and Catharine Titi. 2023. “International Investment Agreements and Foreign Direct Investment: A Survey.” World Economy 46 (6): 1524–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13429.

Egger, Peter and Pfaffermayer, Michael. 2004. “The Impact of Bilateral Investment Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment.” Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp.788-804.

Encavis AG, Fano Solar 1 S.r.l., DE Stern 10 S.r.l. and others v. Italian Republic. ICSID Case No. ARB/20/39, Award, March 2024. https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement/cases/1085/encavis-and-others-v-italy

Energy Charter Treaty. December 17, 1994, 34 I.L.M. 381 (1995). https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2016/01/Energy-Charter-Treaty.pdf.

ESPF Beteiligungs GmbH, ESPF Nr. 2 Austria Beteiligungs GmbH, and InfraClass Energie 5 GmbH & Co. KG v. Italian Republic. ICSID Case No. ARB/16/5, Award. (14 September 2020). https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw11827.pdf.

European Council. 2024. “EU-Angola: Council Gives Final Greenlight to the EU’s First Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement.” Press release. Council of the European Union. March 4, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/03/04/eu-angola-council-gives-final-greenlight-to-the-eu-s-first-sustainable-investment-facilitation-agreement/.

European Parliament. 2024. “Recommendation on the Draft Council Decision on the Withdrawal of the Union from the Energy Charter Treaty. A9-0176/2024. European Parliament: Report – A9-0176/2024.” European Union, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2024-0176_EN.html#_section2.

Furbank, Lani. 2022. “The New Energy Charter Treaty in Light of the Climate Emergency.” Center for International Environmental Law. August 9, 2022. https://www.ciel.org/the-new-energy-charter-treaty-in-light-of-the-climate-emergency.

Gehring, Markus W., Marie-Claire Cordonier Segger, and Jarrod Hepburn. 2012. “Climate Change and International Trade and Investment Law.” In Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781006085.00014.

Global Center on Adaptation and Climate Policy Initiative. 2023. “State and Trends in Climate Adaptation Finance 2023.” GCA. https://gca.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/State-and-Trends-in-Climate-Adaptation-Finance-2023_WEB.pdf.

Global Environment Facility. n.d. “Funding.” GEF. Accessed July 3, 2024. https://www.thegef.org/who-we-are/funding.

Green Climate Fund. n.d. “Resource Mobilisation: GCF’s First Replenishment.” Accessed July 3, 2024c. https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/resource-mobilisation/gcf-1.

International Institute for Sustainable Development. 2022. “Newly Released Text for Modernized Energy Charter Treaty Shows Too Many Potential Obstacles for Climate Action.” IISD. September 13, 2022. https://www.iisd.org/articles/statement/newly-released-text-modernized-energy-charter-treaty.

International Institute for Sustainable Development, and Dihu Wu. 2023. “ICSID Tribunal Finds That Italy Committed an Unlawful Expropriation Under ECT’s Art. 13(1) – Investment Treaty News.” IISD. April 2, 2023. https://www.iisd.org/itn/en/2023/04/02/icsid-tribunal-finds-that-italy-committed-an-unlawful-expropriation-under-ects-art-131/.

International Monetary Fund. 2020. “Fiscal Monitor, October 2020 – Policies for the Recovery.” IMF. October 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/09/30/october-2020-fiscal-monitor.

Ipp, Anja, Annette Magnusson, and Andrina Kjellgren. 2022. “The Energy Charter Treaty, Climate Change and Clean Energy Transition: A Study of the Jurisprudence.” Climate Change Counsel. Climate Change Counsel (CCC). https://www.climatechangecounsel.com/_files/ugd/f1e6f3_d184e02bff3d49ee8144328e6c45215f.pdf.

Johnson, Lise, Lisa Sachs, Brooke Güven, and Jesse Coleman. 2018. “Clearing the Path: Withdrawal of Consent and Termination as Next Steps for Reforming International Investment Law: CCSI Policy Paper.” Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/sustainable_investment_staffpubs/154

Kaufmann-Kohler, G., Potestà, M. 2020. “Why Investment Arbitration and Not Domestic Courts? The Origins of the Modern Investment Dispute Resolution System, Criticism, and Future Outlook.” In: Investor-State Dispute Settlement and National Courts: Current Framework and Reform Options, European Yearbook of International Economic Law Special Issue, ISBN 978-3-030-44164-7: 7–29. Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44164-7_2.

Kingdom of the Netherlands. 2019. “Netherlands Model Investment Agreement.” https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/5832/download.

Kyrgyzstan and India. 2019. “Bilateral Investment Treaty Between the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic and the Government of the Republic of India.” https://jusmundi.com/en/document/treaty/en-india-kyrgyzstan-bit-2019-india-kyrgyzstan-bit-2019-friday-14th-june-2019.

Marshall, Fiona. 2010. “Climate Change and International Investment Agreements: Obstacles or Opportunities?” IISD. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/bali_2_copenhagen_iias.pdf.

Martini, Camille. 2024. “From Fact to Applicable Law: What Role for the International Climate Change Regime in Investor-State Arbitration?” Canadian Yearbook of International Law, March, 2024, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/cyl.2024.2.

McElhiney III, William B. 2014. “Responding to the Threat of Withdrawal: On the Importance of Emphasizing the Interests of States, Investors, and the Transnational Investment System in Bringing Resolution to Questions Surrounding the Future of Investments with States Denouncing the ICSID Convention.” Texas International Law Journal 49, no. 3 (2014): 602.

Moarbes, Charbel A. 2021. “Agreement for the Termination of Bilateral Investment Treaties Between the Member States of the European Union.” International Legal Materials 60 (1): 99–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/ilm.2020.65.

Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency [MIGA]. n.d. “Trust Funds and Blended Finance: What We Do.” MIGA World Bank Group. https://www.miga.org/trust-funds.

Myanmar and Singapore. 2019. “Myanmar – Singapore BIT: Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of Singapore and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar on the Promotion and Protection of Investments.” Electronic Database of Investment Treaties. 2019. https://edit.wti.org/document/show/0edd9101-bae7-4cbe-8a43-f05351bd51a5?textBlockId=5d8d2640-5441-43ea-8651-79d8815d13cc&page=1.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. “Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022: Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal.” OECD. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/environment/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2013-2022-19150727-en.htm.

OECD. 2022. “Investment Treaties and Climate Change: OECD Public Consultation: Compilation of Submissions.” Investment Division, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/OECD-investment-treaties-climate-change-consultation-responses.pdf.

Pauw, W. P., U. Moslener, L. H. Zamarioli, N. Amerasinghe, J. Atela, J. P. B. Affana, B. Buchner, et al. 2022. “Post-2025 Climate Finance Target: How Much More and How Much Better?” Climate Policy 22 (9–10): 1241–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2114985.

Paine, Joshua, and Elizabeth Sheargold. 2023. “A Climate Change Carve-Out for Investment Treaties.” Journal of International Economic Law 26 (2): 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgad011.

Paine, Joshua, and Elizabeth Sheargold. 2023. “A Climate Change Carve-Out for Investment Treaties.” Journal of International Economic Law 26 (2): 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgad011.

Petsch, Markus A. 2019. “The Fork in the Road Revisited: An Attempt to Overcome the Clash Between Formalistic and Pragmatic Approaches.” Washington University Global Studies Law Review 18: 391. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol18/iss2/7.

Pohl, Joachim. 2018, “Societal Benefits and Costs of International Investment Agreements: A Critical Review of Aspects and Available Empirical Evidence.” OECD Working Papers on International Investment, No. 2018/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e5f85c3d-en.

Robinson, Mary. “Investment Treaties Must Be Aligned with Climate Goals.” Speech. 2024 OECD Investment Treaty Conference, March 11, 2024. The Elders. Accessed June 8, 2024. https://theelders.org/news/investment-treaties-must-be-aligned-climate-goals.

RWE AG and RWE Eemshaven Holding II v. Kingdom of the Netherlands. ICSID Case No. ARB/21/4 (2021). UNCTAD Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator. Updated December 31, 2023. https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement/cases/1145/rwe-v-netherlands.

Songwe, Vera, Nicholas Stern, and Amar Bhattacharya. 2023. “Finance for Climate Action: Scaling up Investment for Climate and Development: Report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance.” G20 Global Infrastructure Facility. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.globalinfrafacility.org/knowledge/new-report-independent-high-level-expert-group-climate-finance.

Statista. 2023. “FDI From China into the U.S. 2022.” 2023. Statista. November 3, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/188935/foreign-direct-investment-from-china-in-the-united-states/.

Statista. 2023. “U.S. Foreign Direct Investments in China 2022.” Statista. November 3, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/188629/united-states-direct-investments-in-china-since-2000/.

Tienhaara, Kyla, and Lorenzo Cotula. 2020. “Raising the Cost of Climate Action? Investor-State Dispute Settlement and Compensation for Stranded Fossil Fuel Assets.” ISBN: 9781784318345. IIED. International Institute for Environment and Development. https://www.iied.org/17660iied.

Tienhaara, Kyla, Rachel Thrasher, B. Alexander Simmons, and Kevin P. Gallagher. 2022. “Investor-state Disputes Threaten the Global Green Energy Transition.” Science 376 (6594): 701–3. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo4637.

Tienhaara, Kyla. 2024. “Submission Re: Sharm-el-Sheik dialogue on Article 2, Paragraph (1)(c), of the Paris Agreement and its complementarity with Article 9 of the Paris Agreement (FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.12, para.11” (29 March 2024). https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionsStaging/Documents/202404111552—Sharm_dialogue_Tienhaara.pdf.

UN. 1992. UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. May 9, 1992, S. Treaty Doc. No. 102-38. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf.

UNCTAD. 2014. “IIA Issue Note – Working Draft, the Impact of IIA on FDI: An Overview of Empirical Studies.” 1998–2014.

UNCTAD. n.d. “Mapping of IIA Content.” UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/iia-mapping.

UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance. n.d. “Standing Committee on Finance Meetings and Documents Links.” UN Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/scf/scf-meetings-and-documents.

UNGA. 2022. “Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Climate Change.” UNGA Res. A/77/226. UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. UN. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/a77226-promotion-and-protection-human-rights-context-climate-change.

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, UN, Treaty Series, vol. 1155, p. 331, 23 May 1969, https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/un/1969/en/73676 [accessed 03 July 2024].

World Bank. 2024. “Adaptation Fund.” World Bank Group. June 30, 2024. https://fiftrustee.worldbank.org/en/about/unit/dfi/fiftrustee/fund-detail/adapt.

Yackee, Jason. 2008. “Bilateral Investment Treaties, Credible Commitment, and the Rule of (International) Law: Do BITs Promote Foreign Direct Investment?” Law & Society Review, Volume 42 (2008), p.805.

Footnotes

- Author survey results of IIAs available through the UNCTAD IIA Mapping Project. See: UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub. https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/iia-mapping. [↩]

- Recently, however, a tribunal considered a State’s right to regulate within the context of the UNFCC, stating “States enjoy a sovereign right to amend their laws and regulations and to adopt new ones in furtherance of the public interest. In the global energy transition necessary to achieve the climate change mitigation and adaptation goals pursuant to the UNFCCC and agreements thereunder, it is critical that States are understood to continue to enjoy such sovereign right.” (Encavis v. Italy 2024). [↩]

- For example, in their most recent funding cycles, the GCF pledges totaled $9.9 billion USD (GCF n.d.), the AF pledges totaled $1.05 billion USD (World Bank 2024), and the GEF pledges totaled $4.1 billion USD (GEF n.d.). [↩]

- According to available data, in 2022, U.S. investments made in China were valued at $126.1 billion and Chinese companies invested $28.66 billion in the United States. [↩]