Climate change will increasingly require both homeowners and policymakers to accept the sobering reality that we must move away from our most vulnerable communities.

Introduction

During my twenty years in the U.S. military, any mention of the word “retreat” would initially be met with furrowed brows, heavy sighs, and consternation. After all, retreat conjures negative images of defeat and loss to the enemy. Similarly, climate change is an overpowering “enemy” force that threatens coastal communities.

Climate change will increasingly require both homeowners and policymakers to accept the sobering reality that we must move away from our most vulnerable communities. This will require difficult, heart-wrenching, climate adaptation decisions.

Retreat is an emotionally fraught choice, but often the best option. By one estimate, building sea walls for coastal communities will cost U.S. taxpayers in excess of $400 billion—we simply cannot “accommodate our way” out of climate change.

But rather than seeing retreat as a failure, we must reconceptualize climate change—driven managed retreat for what it presents: a sensible, albeit difficult option that offers fresh opportunities. It represents a mature evolution and acknowledgement of climate change’s true costs, risks, and threats (Siders 2019). But how do we “manage” managed retreat? And what are the legal barriers in doing so?

We are entering the climate–security century as climate change massively destabilizes the physical environment (Nevitt 2015). To meet this physical destabilization, existing laws, regulations, and policies—all designed for a more stable environment—are similarly ripe for destabilization. As we better understand climate change’s “super-wicked” effects, federal, state, and local governments must look with fresh eyes at the full menu of climate adaptation policies and regulatory tools at our disposal (Lazarus 2009).

But these laws, regulations, and policies evolved slowly over time in response to mere incremental changes in the physical environment. Laws and policies suitable for a stable “Earth 1.0” are not up to the climate challenges in our destabilized “Earth 2.0.”

One such adaptation measure—managed retreat—increasingly demands our attention. Defined by Professor A.R. Siders as the “purposeful, coordinat[ed] movement of people and assets out of harm’s way,” managed retreat is a forward-looking adaptation tool that can save homes and lives (Siders 2019). Yet we lack a coherent managed retreat policy at any level of government. Indeed, managed retreat decision-making and implementation occurs haphazardly and reactively.1

Exacerbating matters, how we manage managed retreat faces legal hurdles and outdated doctrines designed for “Earth 1.0.” It also raises fundamental questions of equity and environmental justice—those with the greatest resources have better options to move their homes while poorer communities may well be stuck. Properly “managing” managed retreat will require a massive, normative reconceptualization of existing laws and policies (Coglianese 2020). Frontline communities in the U.S. are already suffering: since 1955, the community of Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana has lost 98 percent of its land to the Gulf of Mexico.

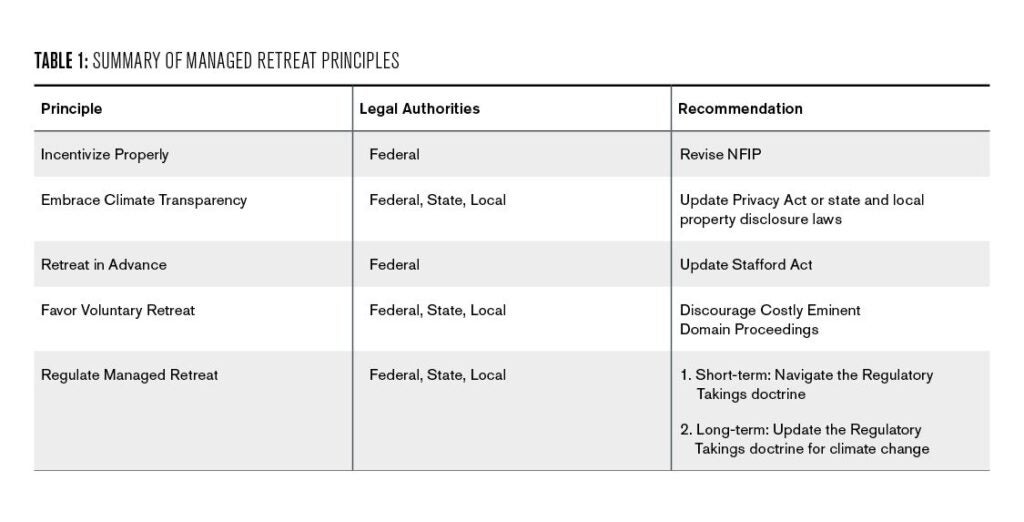

In what follows, I propose five principles to guide equitable managed retreat decision-making. It identifies legal tension points that should be reexamined to systematically set the conditions for equitable managed retreat. It concludes by applying these principles to Norfolk, Virginia—a city already at the frontlines of managed retreat.

Principle #1: Incentivize and Acknowledge Climate Change’s True Costs

Any managed retreat strategy requires that we have the proper incentive structures in place. And the regulatory landscape must take into account climate change’s true costs. We can’t over-subsidize building in climate-prone areas, and we must price climate change’s costs accurately and transparently.

But we are failing to even meet this minimum standard: for decades, federal policy has subsidized building in the flood zone via the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) of 1968. This facilitates a cycle of destroy-rebuild-repeat within the flood zone (Klein 2019).

For any managed retreat strategy to succeed, Congress must transform—or carefully eliminate—NFIP to take into account climate change’s increased costs while discouraging repetitive loss payouts. But eliminating NFIP must take place equitably: it must first do no harm to our most vulnerable communities that rely heavily upon reduced flood insurance premiums to keep their homes.

Just consider the costs of our business as usual approach. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA), climate change will cause an increase in recurrent flooding and sea level rise, further exposing federally subsidized homes to flood risks (National Climate Assessment 2018). Since the 1960s, sea level rise has increased the frequency of high-tide flooding by a factor of 5 to 10 for several U.S. coastal communities (National Climate Assessment 2018).

From 1978 to 2018, more than 36,000 NFIP-insured properties filed repeated claims for flood damage. One study found that a single home in Mississippi was rebuilt 34 times in 32 years using $663,000 in federal tax dollars—for a home worth only $69,000 (Siders 2019).

NFIP has been used to buy out homeowners willing to relocate, but that pales in comparison to the money spent on repairing and rebuilding existing properties. The existing NFIP incentive structure is outdated, does a disservice to taxpayers, and does not properly take into account future, climate-exacerbated flood risks.

For any managed retreat strategy to succeed, we must set the right voluntary retreat conditions and fully account for climate risk. Restructuring NFIP to better incentivize voluntary retreat would be a critical first step to recalibrate the incentive structure to take into account climate change’s true costs.

To be sure, important tradeoffs will have to be made as premiums rise and people cannot afford the new premium costs—the devil will be in the details. But if this is executed nimbly and equitably, this could present a rare, climate “win-win.” We could stop the cycle of “destroy-repair-repeat” (Sack and Schwartz 2018).

And the most vulnerable NFIP homes could be knocked down and transformed into green space that aids in floodwater retention. This is already occurring in New Jersey via the Blue Acres Floodplains Acquisitions Program. This first principle—incentivize properly—should guide policymakers as they wrestle with climate change’s true risks in the flood zone.

Principle #2: Embrace Climate Transparency

Justice Brandeis once famously stated that “sunlight was the best disinfectant” (Brandeis 2014). Yet climate change’s true risks and associated costs are too-often obscured. The stakes in hiding climate risk are stunning: a recent joint report by Climate Central and Zillow found that we are on a path to place 3.4 million existing homes worth $1.75 trillion at increased flood risk by the end of this century (Singhas 2019).

For most homebuyers, buying a home is the single most important financial decision that they will make in their lifetime. And flood-caused water damage remains the greatest risk to that investment (Singhas 2019). But flood-risk reporting requirements are not uniform and mandatory across all states (Peri, Rosoff, and Yager 2017).2

Prospective homeowners often lack access to key information: under the Privacy Act, FEMA only provides current owners with access to the full, flood claims history (Darlington 2018).3 Right now, this information is a protected “record” within the meaning of the Privacy Act (5 U.S.C. § 552a).

Too often, homeowners must rely upon state and local real estate disclosure laws that are, literally, all over the map. At last count, 21 states—to include Virginia—do not require home sellers to notify prospective buyers that the home is in a flood zone (Morrison 2020). Furthermore, these flood maps and flood disclosures are backward-looking; they fail to address future climate projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or the National Climate Assessment (Briscoe and Song 2020).

Why? By one estimate, close to six million homeowners may be susceptible to flood risk, and not even know it (Briscoe and Song 2020). Climate change’s impact on sea level rise and recurrent flooding mandate that we embrace climate transparency, ensuring that all relevant—and future—flood risks are fully available.

A recent joint report by Climate Central and Zillow found that we are on a path to place 3.4 million existing homes worth $1.75 trillion at increased flood risk by the end of this century.

Ensuring climate–risk “sunlight” in the homebuying process should be pursued, but how? First, we must use updated information that accurately reflects a property’s flood risk. Second, we must make such disclosures (to include past claims) easily available to prospective buyers.

Remarkably, prospective buyers of used cars have greater access to such information via CARFAX, a widely available auto-disclosure tool that provides a wealth of information for prospective auto buyers (Morrison 2020). If you know a used car’s history, shouldn’t you have the same information for your home and neighboring properties?

For too many homeowners today, home purchases in suspected flood zones are less a confidence-inducing exercise and more an emotional, time-compressed leap of faith. For markets to work efficiently, participants need full and reliable information about the risks behind a purchase. While climate science will likely never be able to tell us with precise details the location and timing of a future flood event, past flooding events can inform our decision-making process.

Embracing climate transparency could come about in any number of ways. The Senate could pass the 21st Century Flood Reform Bill, which would make this information more accessible.4 Each state could update their flood-disclosure laws. The Privacy Act could be updated to carve out an exception for flood claims information that is readily accessible.

Alternatively, FEMA could condition future NFIP payouts on mandatory purchase disclosures. Or the IRS could condition claiming the mortgage interest deduction on having received a flood disclosure.5 But implementing either option may raise constitutional problems.6

Regardless of how we shine light on flood risk, the adoption of a commonly accepted “FLOODFAX” for all homes, complete with claims history, would be welcomed. This second principle of managed retreat—embrace climate transparency—favors equitable access to flood risk information.

Principle #3: Retreat in Advance, Don’t Just Rebuild in Response

Third, climate change will also force us to question the logic of our governing emergency response legal framework. The Stafford Act and the patchwork of laws and FEMA regulations governing federal emergency response largely react to extreme weather events after they occur.

If you know a used car’s history, shouldn’t you have the same information for your home and neighboring properties?

As the price of this emergency response increases, we must shift from an ex post (reactive) approach to an ex ante (proactive) approach. Yet we continue to build in climate-vulnerable areas following natural disasters, oftentimes at astonishing rates.

We already know that climate change will cause an uptick in extreme weather. Indeed, the American Meteorological Society recently found that climate change increased both the likelihood and severity of 15 of 16 recent extreme weather events (American Meteorological Society 2017).

By failing to take into account advances in climate science, our federal emergency response framework suffers from climate myopia, ignoring climate-driven extreme weather events. Homeowners in exposed coastal communities take comfort that Uncle Sam will come to the financial rescue in a natural disaster’s aftermath; just witness the cycle of destroy-repair-rebuild that occurred following Hurricanes Sandy, Maria, Florence and Michael.

Under our federalism system, federal taxpayers foot the bill for costly rebuilds while state and local officials make the bulk of local land use decisions. Tough political decisions are put off while the federal money flows.

Yet there are some glimmers of hope in reconceptualizing our emergency response framework from a reactive one to a proactive one. Congress recently updated the Stafford Act by passing the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA). The DRRA represented a tangible step in moving funds from post-disaster assistance to pre-disaster mitigation. We should build on this work to set the conditions for voluntary managed retreat.

This third principle—retreat in advance, don’t rebuild in response—should guide lawmakers as they update the Stafford Act and FEMA regulations for our destabilized Earth 2.0.

Principle #4: Favor Voluntary Managed Retreat over Forced Managed Retreat

For any managed retreat strategy to succeed at scale, it should encourage voluntary retreat, not mandate forced retreat. The first three principles outlined above help set the conditions to do just that. Besides being heavy-handed and politically contentious, forced managed retreat runs headfirst into a significant—and costly—constitutional issue. The Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause states that private property “shall not be taken for public use without just compensation.”

In Kelo v. City of New London, what constitutes a “public use” was expanded to encompass the governmental taking of private property for purposes of economic development. In the aftermath of Kelo, the property taken by any governmental entity via eminent domain proceedings as part of a broader managed retreat strategy would likely qualify as a public use.7That’s good news for climate adaptation efforts, but eminent domain still requires just compensation payouts to each affected property owner.

For states and localities, this is simply an unaffordable option.8To be sure, such actions could be used as a last resort when there is a clear and present climate danger. But just as we cannot “accommodate our way” out of climate change, we can’t “buy our way” out via a massive forced retreat policy. We must favor voluntary retreat over forced managed retreat—subject to the second-order legal issues discussed below.

Principle #5: Regulate Managed Retreat—Be Bold (But not Too Bold)

Justice Brandeis also stated that “we must let our minds be bold.” States and localities should serve as “laboratories of democracy” and experiment boldly as part of our federalism system of government (Brandeis 1932). Climate change will necessitate that states and localities pass forward-looking zoning laws and climate adaptation regulations. But this, too, may runs afoul of legal issues. Beyond physical takings, the Fifth Amendment also encompasses so-called regulatory takings. This includes the governmental regulation of private property, delivering a chilling effect for future climate adaptation efforts (Scalia 1992).

The regulatory takings doctrine could thwart the most forward-looking and ambitious climate adaptation measures governing managed retreat. Indeed, offshoots of the regulatory takings doctrine may already be discouraging proactive, well-intentioned, actions necessary to address climate change’s future impacts on sea level rise, storm surge, and flooding.

If climate–focused adaptation laws are too bold—they go “too far” in regulating private property rights—the regulatory takings doctrine kicks in (Holmes 1922). This could serve as a chilling effect and legal barrier to bold climate adaptation regulations.

Further complicating matters, climate adaption policies must take into account both governmental action and inaction (Serkin 2014). For communities particularly vulnerable to sea level rise or extreme weather, governments may seek to terminate municipal services, stop repairs to coastal access roads, or provide notice that emergency services may not be available. This “live or build at your own risk” approach may also be subject to a regulatory takings claim as homeowners assert that governmental disinvestment cuts their homes off from the broader community, diminishing their property’s value.

Long-term, courts may have to circumscribe the regulatory takings doctrine to take into account our changing environment—but this promises to be difficult and controversial. In the interim, governments must follow this fifth principle—acting boldly on climate adaptation efforts, but not too boldly. This requires walking a legal tightrope between action and inaction, between acting boldly—as Justice Brandeis exhorted—and taking no action. A summation of these five managed retreat principles is provided in Table A.

The Five Managed Retreat Principles in Action: Norfolk, VA

In Norfolk, the seas are rising, and the soil is sinking. It is also home to the largest concentration of military and national security infrastructure in the world with shipyards, air stations, and military installations dotting the Hampton Roads landscape—a loose confederation of 17 localities in southeast Virginia. Naval Station Norfolk boasts the world’s largest naval base and serves as an economic engine for the broader Hampton Roads community.

Because of Norfolk’s strategic importance and its vulnerability to climate change, it is at the leading edge of adaptation and managed retreat discussions. Indeed, Former Vice-President Al Gore has previously stated that Norfolk Naval Station must be relocated at some point—“it is just a matter of when” (Goodell 2019). Climate change’s impacts have already arrived at Norfolk with sea level rise, and recurrent flooding constant worries.9How will Norfolk manage this managed retreat?10 And what are the stakes?

Under the first principle—incentivize properly—there must be a change in federal law or regulation to modify the National Flood Insurance Program to discourage building in climate risk-prone areas. The military is outside of NFIP; it self-insures, effectively sending the bill to the American taxpayer following a natural disaster.11

By one estimate, Norfolk has 1,000 properties at risk and that number will grow (Morrison 2020). Passing the previously mentioned 21st Century Flood Reform Bill would mark a step in the right direction in getting the underlining incentives correct and Congress should build upon its work addressing building in floodplains on military installations.

Applying the second principle—embrace climate transparency—would surely help the long-term health and stability of homes in Norfolk as well as the surrounding Hampton Roads communities. Right now, Virginia law does not mandate that for buyers and builders be warned that they are moving into a flood zone.

Despite its exposed coastline, Virginia received an “F” in a recent analysis of flood disclosure laws by the Natural Resources Defense Council. Further, new homes built in an undisclosed floodplain today will be a long-term millstone around the city’s neck as it continues to provide emergency services, maintain access roads, and invest in infrastructure. At a minimum, the Virginia legislature should do no harm, price risk accurately, and take the long-view—embrace climate transparency by passing mandatory flood disclosure laws.

Applying the third principle—retreat in advance, don’t rebuild in response also relies heavily upon the federal government to reform the Stafford Act and governing FEMA regulations. Exigent circumstances may require this.

Congress should build off its pre-COVID efforts to reform the Stafford Act via the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA) and look at providing resources in advance of natural disasters, not after. We must increasingly manage retreat in advance, and disfavor issuing payouts in response.

Applying the fourth principle—favor voluntary retreat over forced retreat—will be the default option out of pure necessity in Norfolk. While Norfolk recently purchased four homes as part of a buyout program, providing compensating homeowners through eminent domain proceedings remains both politically contentious and fiscally prohibitive.

Forced retreat will increasingly not be an option (Morrison 2020). As discussed below, voluntary retreat is more likely to occur through the systematic passing of zoning laws and implementing existing plans.

Norfolk likely has the largest leeway in applying the fifth managed principle through seeking bold climate adaptation measures. Thankfully, Norfolk has already begun the hard work of planning its climate-driven future with the release of Norfolk Vision 2100 and PlaNorfolk 2030. And the city has modified its zoning laws to better take into account sea level rise and climate-related impacts.

Norfolk must find a true “Goldilocks” approach in planning for the future while not discouraging investment in Norfolk nor running afoul of the regulatory rakings doctrine. And it must continue to work with military leaders, Congress, and others to synchronize whole of government adaptation efforts.

Conclusion: Re-conceptualizing Retreat

Climate change is a “super wicked” problem that will require large-scale, normative change throughout society. This takes time: witness the long march for civil rights, women’s rights, and marriage equality. And, still, the work continues. Yet we must set the conditions for normative change. This means updating our “Earth 1.0” laws, regulations, doctrines, and incentive structures to take climate change’s impacts into account. As Professor Cary Coglianese and I have previously argued, we are already paying a hidden climate tax that is “hidden, unfair, and ever-increasing” (Coglianese and Nevitt 2019).

Climate change is a massive, natural “enemy” force that will require us to reconceptualize retreat. To do so will require a shift from focusing on what is lost to what is being gained: a safer, more resilient community that is ready to meet the climate challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

I began this essay by highlighting the negative initial reactions associated with retreat that I experienced while I served in the military. What I did not mention is that this initial skepticism often turns to sobering acceptance. A well-executed managed retreat is often the most sensible short–term option in the face of an overpowering enemy force.

Similarly, a well-managed climate retreat allows us to regroup, minimize losses, and consolidate resources. Climate change is a massive, natural “enemy” force that will require us to reconceptualize retreat. To do so will require a shift from focusing on what is lost to what is being gained: a safer, more resilient community that is ready to meet the climate challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

Just like in the military we can live to fight—and live—another day. Following these five principles are merely a start to help ensure a safer, more equitable future that is ready for our destabilized “Earth 2.0.” The question remains: will we be up to the challenge?

Mark Nevitt

Associate Professor, Syracuse University College of LawMark Nevitt is an associate professor of law at Syracuse University College of Law. He was previously Lecturer in Law, Sharswood Fellow at Penn Law and also a law professor at the U.S. Naval Academy.

American Meteorological Society. 2019. “Explaining Extreme Events of 2017 from a Climate Perspective”.

Brandeis, Louis. 1932. New State Ice Co. V. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 311.

Brandeis, Louis D. 1914. “Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It.” F.A. Stokes. 92.

Briscoe, Tony and Lisa Song. 2020 “Millions of Homeowners Who Need Flood Insurance Don’t Know It — Thanks to FEMA.” Propublica. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.propublica.org/article/millions-of-homeowners-who-need-flood-insurance-dont-know-it-thanks-to-fema

Coglianese, Cary. 2020. “Climate Change Necessitates Normative Change.” The Regulatory Review.

Coglianese, Cary and Mark Nevitt. 2019. “Actually, The United States Already Has a Carbon Tax.” Washington Post. Accessed January 23, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-united-states-already-has-a-carbon-tax/2019/01/23/9f02c3a8-1f56-11e9-8e21-59a09ff1e2a1_story.html

Darlington, Abigail. 2018. “Little-known Federal Law Keeps Buyers From Finding out if a Home Routinely Floods.” Post Courier. Accessed August 9, 2018. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/little-known-federal-law-keeps-buyers-from-finding-out-if/article_9e348564-9b13-11e8-934c-6ffa499e136b.html

Flavelle, Christopher. 2020. “Rising Seas Threaten an American Institution: The 30-Year Mortgage.” New York Times. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/climate/climate-seas-30-year-mortgage.html

Flavelle, Christopher and Patricia Mazzei, 2019 “Florida Keys Deliver a Hard Message: As Seas Rise, Some Places Can’t be Saved.” New York Times. Accessed December 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/04/climate/florida-keys-climate-change.html

Garner, Bryan. 1999. Black’s Law Dictionary. Saint Paul: West Group, 469.

Goodell, Jeff. 2017. “The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World.” Little, Brown, & Company. 191.

Holmes Jr., Oliver Wendell. 1992. Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 412, 415.

Klein, Christine A. 2019. “The National Flood Insurance Program at Fifty: How the Fifth Amendment Takings Doctrine Skews Federal Flood Policy.” Georgetown Environmental Law Review 285, 31.

Lazarus, Richard. 2009. “Super Wicked Problems and Climate Change: Restraining the Present to Liberate the Future.” Cornell Law Review 1153, 94.

Mach et. al. 2019. “Managed Retreat Through Voluntary Buyouts of Flood-Prone Properties.” 5 Science Advances, 5.

Morrison, Jim. 2020. “Climate Change Turns the Tide on Waterfront Living.” Washington Post Magazine. Accessed April 19, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2020/04/13/after-decades-waterfront-living-climate-change-is-forcing-communities-plan-their-retreat-coasts/?arc404=true

National Climate Assessment (Fourth edition) 2018. nca2018.globalchange.gov

Nevitt, Mark P. 2015. “The Commander in Chief’s Authority to Combat Climate Change.” Cardozo Law Review, 37, 439.

Peri, Caroline, and Stephanie Rosoff and Jessica Yager. 2017. “Population in the U.S. Floodplains,” NYU Furman Center, 2.

Privacy Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552a.

Sack, Kevin and John Schwartz. 2018. “As Storms Keep Coming, FEMA Spends Billions in Cycle of Damage and Repair.” New York Times. Accessed October 8, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/08/us/fema-disaster-recovery-climate-change.html

Serkin, Christopher. 2014. “Passive Takings: The State’s Affirmative Duty to Protect Property.” Michigan Law Review, 113: 345.

Siders, A.R. 2019. “Managed Retreat in the United States.” One Earth Perspective.

Singhas, Sarah. 2019. “Digital Dialogue No. 2: Improving Flood Risk Disclosure,” Wharton Risk Center. Accessed January 2019. https://riskcenter.wharton.upenn.edu/digital-dialogues/improving-flood-risk-disclosure/

U.S. Constitution Amendment V.

- While laws have not kept pace with our new climate reality, managed retreat toolkits and policy documents are beginning to take shape. This includes the work of the Georgetown Climate Center and their efforts on developing a managed retreat toolkit, available here [↩]

- It is estimated that more than 30 million people live in the combined floodplain. Peri, Rosoff and Yager, 2017 [↩]

- And current homeowners must make this request in writing. [↩]

- As of this writing, the House of Representatives has passed this bill, but the Senate has not yet brought the bill to the floor. [↩]

- In other contexts, climate risk is already calling into the question the future viability of the 30-year mortgage loan program. Flavelle 2020. [↩]

- This does raise a constitutional issue whether such conditions can be imposed on the state or mortgagee that is beyond the scope of this article. [↩]

- Eminent domain is defined as “the inherent power of a governmental entity to take privately owned property, especially land, and convert it to public use, subject to reasonable compensation for the taking.” Garner 1999. [↩]

- And one that the COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate as states and localities suffer from budgetary shortfalls. [↩]

- As a personal anecdote, during my first day of work in 2012 at Norfolk Naval Station I was unable to get home from work due to a flooding event. Such events are increasingly common in Norfolk. [↩]

- As a fundamental matter, the Commonwealth of Virginia does not delegate all authority for localities such as Norfolk to pass zoning laws and related climate adaptation measures. Virginia is what is known as a Dillon’s Rule state—Norfolk may only exercise those powers that the state expressly grants to it. [↩]

- This can be a costly endeavor, as Hurricanes Florence and Michael caused billions of dollars of damage at military bases in North Carolina and Florida. [↩]