What’s Behind Poland’s Opposition to EU Climate Neutrality Agreement

EU leaders have endorsed climate neutrality by 2050 but Poland remained opposed and was granted an exemption, citing mostly economic concerns in a country dominated by coal. Explore the politics behind Poland's opposition.

European Union leaders have just endorsed the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. The agreement has not been a complete win, however, as Poland remained opposed to the action and was granted exemption with negotiations to reopen in June 2020. The country cited mostly economic concerns about transforming the economy, where in 2018 almost 80 percent electricity was still generated from coal.

But while economy is an important and necessary part of the equation, it is not the only factor that is guiding Poland’s resistance against decisive climate action. Instead, one also needs to consider the electoral dynamic that has been a key for coal’s persistence in Poland. Understanding this dynamic in Poland can shed some light on how elections can affect coal’s fate in other parts of the world.

Coal has been the one domestically available resource that allowed Poland to grow and develop economically and provided an important cushion as the country experienced energy security issues related to natural gas imports. But coal is becoming less competitive as EU’s cap-and-trade system has systematically increased the price of carbon. And due to the opening of the LNG import terminal in Swinoujscie and plans for renewable development on the Baltic Shore, coal has been losing some of its energy security premium. Poland’s long history of coal mining and an affinity toward miners is now also threatened by increasing concerns about environmental degradation and climate change.

What has not changed, however, is the electoral setup, where governments irrespective of party colors have to seriously consider the preferences of a mining-dependent population.

Here is why.

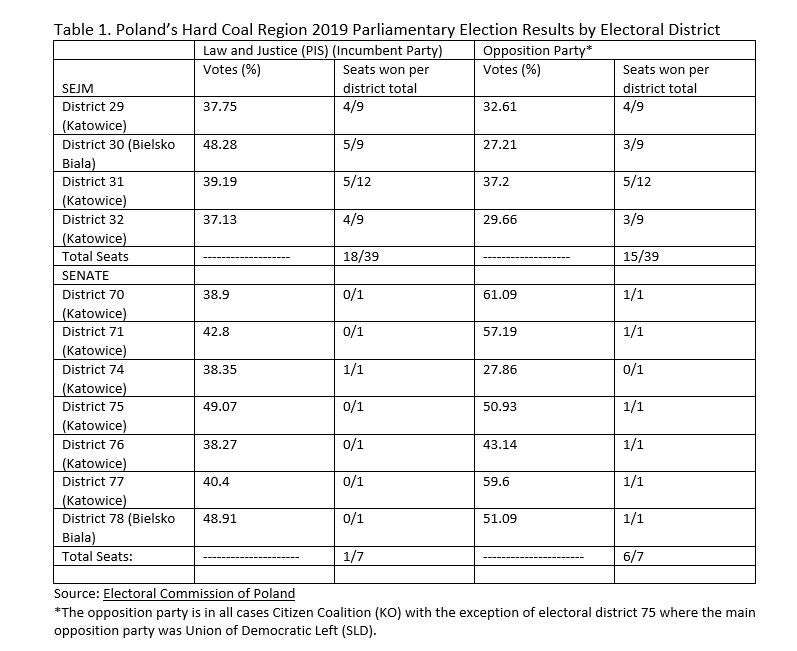

Just the hard coal producing regions in Poland’s Upper Silesia region provide 39 seats in the 460 seats in the Sejm (lower chamber of parliament) and 7 out of 100 seats in the Senat (Senate or upper chamber). In a country that has only recently managed to form a governmental majority and where this majority is at stake at each and every election, losing any seat can make a difference between governing without distractions and having to share power with a junior coalition partner.

In addition, the seats in the Upper Silesia hard coal mining region are far from secure. Instead they are usually very close, with the main governing and opposition parties gathering about the same amounts of votes and seats (See Table 1 for the breakdown of votes in the region in 2019 parliamentary elections).

This is even more pronounced in the Senate election where single mandate districts and a winner-takes-all system pushes the stakes even higher. Neither party can afford to displease even the tiniest part of the population, especially the typically unionized miners. As a result, parties in power are more concerned with domestic factors in favor of coal than with the EU regulations or global climate trends.

Not adhering to EU laws or global climate commitments can bring on EU fines and harsh words from the international community, but none of this can unseat the party in power. On the contrary, well organized and geographically concentrated miners can.

Analysis and Conclusions

Poland illustrates why in countries with significant coal deposits, elections could be a very important factor in deciding whether or not give up coal:

- Coal deposits are territorially concentrated and coal mining is labor intensive, which leads to large mining populations in coal regions.

- Coal mining has been generally characterized by strong unionization and politically active labor unions.

- Political power of mining populations in coal regions can be augmented if elections in the region are close or when the electoral system is based on the winner-take-all principle.

- Political power of coal regions is strongest in highly competitive (close or winner-take-all) national elections where no party can afford to lose a seat.

In a world that increasingly engages in climate action and pushes for new energy sources and technologies, Poland is an important reminder that not only economic or geo-economic but also domestic political factors need to be addressed to accomplish energy policy goals. There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to carbon emissions or fossil fuel use. Only once we recognize that these strong political forces exist can we explore effective solutions.

Anna Mikulska

Senior FellowAnna Mikulska is an expert on European energy markets and energy policy. She is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center and a fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.