Meeting Paris Agreement Targets Requires an Orderly Transition

This year's COP signaled an end to all-or-nothing thinking on climate efforts. We need to deploy renewables, and we need resources that can produce energy when the sun is not shining, or the wind is not blowing. The transition away from fossil fuels must be orderly, or the transition itself is at risk.

In order to limit global temperature warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F), the world must achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Under the Paris Agreement, meeting these targets requires that countries develop their own “Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs),” describing their mitigation responses. The United States, for example, has both an economy-wide greenhouse gas emission reduction target and sector-specific targets.

Moving from a mostly fossil-based electricity system to one based on clean energy is a key part of achieving Paris Agreement targets, and the transition must be orderly.

Paris Targets Are Not on Track

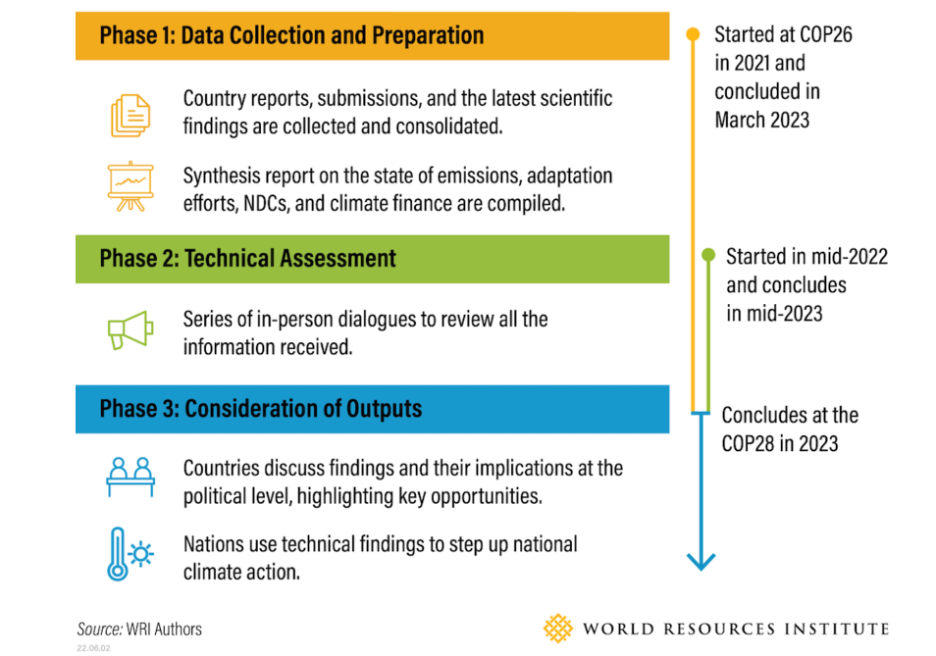

Before this year’s Climate of the Parties, or “COP,” countries already knew that existing NDCs, the targets set by individual countries to meet Paris Agreement targets, would be insufficient to meet global targets. The first global assessment (“global stocktake”) of NDCs took place over the last several years. The final analysis concluded that “the parties are not yet collectively on track towards achieving the purpose of the Paris Agreement and its long-term goals.”

Specifically, under existing NDCs, global temperatures will likely rise 2.1-2.8°C and “policies implemented by the end of 2020 result in higher global greenhouse gas emissions than what the NDCs would imply.”

While it’s not quite “blah, blah, blah,” since without action already taken expected global temperature increases would have been 4°C, there is still an implementation gap between global targets and measured reality.

Transitioning from Fossil Fuels

At this year’s COP, much of the discussion focused on how to design mitigation mechanisms that could meet global targets, since countries must now set even more ambitious targets for the next set of NDCs, due in 2025.

The final stocktake agreement reached at the COP calls for “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly, and equitable manner” by 2050. Further, it recognizes “that transitional fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security.” In other words, countries recognized the need to transition and that some fossil fuels are needed until there is something available to replace them.

While this signals the “beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era,” it is also a recognition that renewables and energy efficiency are necessary, but not sufficient, to achieve global targets. Some other, not-yet-commercial technologies, like advanced nuclear, hydrogen, or abatement and removal technologies are also needed.

An End to All-or-Nothing Thinking

The decarbonization challenge is an electricity sector challenge. Decarbonizing heating and transportation means electrifying these sectors. Managing the reliable, affordable, and equitable transition of the electricity sector—in support of these targets—requires coordinated policy, coordinated planning, and cross-sector integration across regulatory silos.

Despite criticism that the agreement reached at COP allows fossil fuels to remain, managing the reliable, affordable, and equitable transition of the electricity sector requires that we move beyond all-or-nothing framing and recognize the reality of the transition is “both/and.”

We need to deploy renewables, and we need resources that can produce energy when the sun is not shining, or the wind is not blowing. Today, battery storage and natural gas resources are commercially available technology that provide this critical function. For this to be something other than fossil, requires focused and coordinated policy. In the United States, we do not have the kind of coordinated policy, planning, and cross-sector integration it takes to actually manage the reliable transition of the electricity sector.

We need to increase energy efficiency efforts, and we need to scale batteries and not yet commercial technologies, like advanced nuclear, hydrogen, or carbon abatement and removal technologies to fully decarbonize and move beyond remaining gas.

We need to recognize geopolitical realities and we need to meet climate targets. We need to phase out fossil, and we need to maintain grid reliability throughout the transition.

Implementation is hard because implementation is about politics and power flow. Ignoring geopolitical realities that impact energy security, and the need to maintain reliable electric systems, risks making choices in this critical decade about reliability versus climate. We must ensure the reliable transition of the electricity sector in support of energy security goals. The transition away from fossil fuels must be orderly, or the transition itself is at risk.

Kelli Joseph

Senior Fellow, Kleinman CenterKelli Joseph is a Kleinman Center Senior Fellow. She works at the intersection of policy and markets, with a focus on transitioning the electricity sector to support a decarbonized, climate resilient economy.