Energy Transitions Past and Future: How History Museums Affect Policy Today

Climate scientists cite the industrial revolution as a major factor in the climate crisis. So why aren’t we telling the climate story at heritage sites dedicated to industrial history?

Climate scientists cite the nineteenth century’s industrial revolution as a major factor behind the climate crisis. Across the United States, historic sites preserve and celebrate the innovation, wealth, and social transformation of this period. From heritage railways and restored factories, to coal miner villages and oil baron mansions, there are many opportunities to immerse yourself in the history of this period. However, I have found that few of these heritage places include the history of the climate crisis in their educational programming.

Climate change is increasingly recognized as a cultural issue. The technology for a green energy transition is available, yet catastrophic emissions continue. Policy is key to pushing the transition forward, but policy works in tandem with culture for solutions to be accepted and adopted.

Museums play an important role in shaping American culture. In their 2021 national study on museums and trust, the American Alliance of Museums found that museums continue to transcend political polarization and rank second only to friends and family as the most trusted source of information—above scientists, government, and news. Science and even art museums are beginning to provide information about the climate crisis, but history museums have lagged far behind.

To support new initiatives in this area and demonstrate what is possible, I founded the Climate Crisis Heritage Project. And a grant from the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy allowed me to visit the Lowell Mills National Historical Park in Massachusetts to prototype climate change educational materials at a historical site.

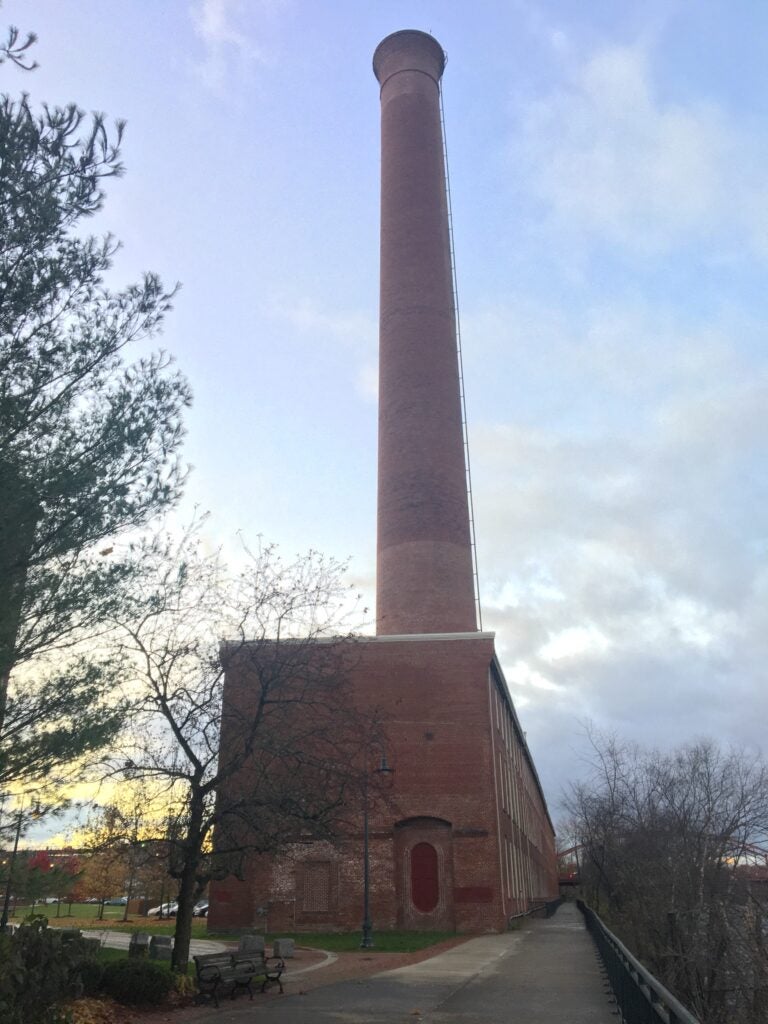

What would it look like to tell the climate story to students and sightseers visiting this park? Staff at Lowell Mills National Historical Park were interested in exploring this question with me. Lowell is one of the earliest industrial cities in the Northeast United States. It was founded in 1823 on waterpower, but by the turn of the century the factories used more coal power than water. The site hosts more than 500,000 visitors per year and includes restored factory buildings, worker dormitories, working 19th century looms, and preserved water turbines and smokestacks: a progression of artifacts and structures that chart the expansion of the economy through fossil fuel power.

While visiting Lowell, I familiarized myself with its historic resources, and workshopped ideas with the staff. My host was Jamie Smith, associate director of the Tsongas Industrial History Center at Lowell. Jaimie and her staff work in the education department and manage deeply researched and thoughtfully interactive field trips for busloads of middle- and high-school students.

In collaboration with Jamie and her team, I drafted a historic context for Lowell’s relationship with the history of climate change. The team is working to augment a field trip curriculum about power at Lowell to include information on the fossil fuel energy transition and climate change.

Lowell will test the revised field trip with students and teachers this spring. We’ll present our project at a panel I have organized with renowned public historian Donna Graves, Cultural Emergency Response: Interpreting the Historic Context for Climate Change, at the National Council on Public History Annual Meeting in April 2023.

History museums and historic sites are an untapped resource for giving the public context for the causes of today’s climate crisis. And historic places like Lowell that preserve the history of earlier energy transitions provide concrete—and hopeful—evidence that national energy transitions are possible.

Aislinn Pentecost-Farren

MFA/MSHP Candidate, Weitzman SchoolAislinn is an artist and curator who consults and collaborates with parks and heritage sites. Aislinn’s dual Master of Fine Arts and Master of Science in Historic Preservation degree will be the first one awarded by the Weitzman School of Design.