CleanTech SPACs: Friend or Foe for the Regulators?

If we want to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, we will need big changes in our nation’s mobility and infrastructure systems. Financial innovation can be an ally in this fight.

2020 was the year when Wall Street found its new darling: Special Purpose Acquisition Vehicles (SPACs). Last year, there were 248 SPAC Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) worth $83 billion, representing nearly half of all IPOs and in sharp contrast to the mere 225 SPAC IPOs in the last decade.

About $14.3Bn (~17%) of last year’s proceeds went to ESG-compliant (Environmental, Social, Governance friendly) companies, roughly half of it specifically to firms in the electric vehicle industry, and the rest to those firms developing clean technologies. SPACs, despite their shortfalls, should become a significant tool in our battle against climate change as we try to scale these green businesses.

SPACs are essentially shell or “blank check” companies that go public and pool money from investors with the intention of acquiring another private company later and making that company public much quicker and easier than a traditional IPO process. The innovative financial structure of SPACs also allows for the de-risking of acquired companies, which unlocks a significant amount of capital for early-stage, high-growth companies, and makes them accessible to both large fund managers and retail investors.

What makes this new source of financing so crucial for cleantech and EV companies is that those firms’ business models differ from the typical consumer mobile apps or SaaS solutions. These firms are in still relatively nascent industries, particularly EV and storage projects.

They face highly regulated and capital-intensive markets and burn cash at faster rates while delivering slower returns. Since this new liquidity and de-risking makes them more attractive for public markets, it also fills the void in the U.S. where government funding and support hasn’t been as prevalent as in China or Europe.

All around the world, governments are making commitments to reduce the carbon footprint of their energy and mobility industries, and institutional investors of all shapes are looking for socially responsible investments that would position them well from a regulatory and competitive perspective.

SPACs are helping build this transition to a low-carbon economy as they get more investments. On the mobility front, we see investment in EV manufacturers such as Nikola, their suppliers such as battery makers, and charging infrastructure firms such as EVgo all crucial for EV’s mass adoption.

Meanwhile, SPAC targets also include more established companies working on renewable energy production, energy storage, and new transmission networks. Lastly, SPACs are benefiting next-generation technologies such as carbon sequestration and hydrogen cells.

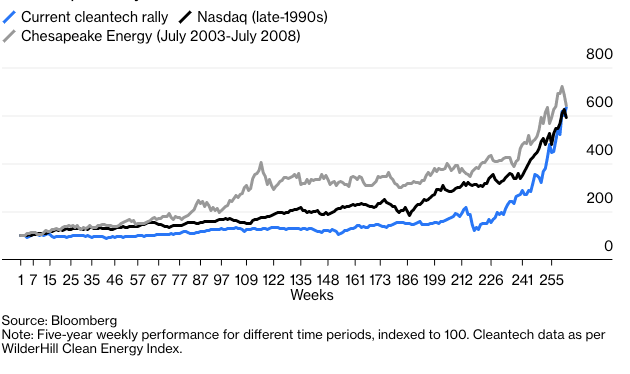

The SPAC market has drawn wide criticism though, and shows signs of a bubble according to many investors who draw parallels with previous bubbles. Still, the benefits of this hot market may outweigh its potential dangers: unlike the recent oil and gas shale boom and bust, the SPAC cleantech firms are not loaded up with outsized debt by banks, and unlike the cleantech / renewable energy bubbles of mid-2000s and early 2010s, the technologies that are being used (particularly in the energy / infrastructure space) are both more mature and cheaper.

This market is more comparable to the wild dot-com days, with lofty valuations despite lack of commercial track records. Cases like Nikola, whose market cap is almost 1/7th of what it was last summer in its peak (due to various allegations) serve as cautionary tales. In a similar way, some firms will go bust, and the strongest ones will survive as the markets correct themselves.

Recently, the SEC has begun investigating four SPAC-backed companies and opened up a general inquiry to investment banks’ SPAC involvements, as well as raised investor-protection concerns.

As Democrats want to scrutinize IPOs and public markets more harshly than their predecessors, they shouldn’t seek to crack down on SPACs or put policies in place that would stifle their growth. Given the increasing involvement of large investors in SPAC deals through PIPEs (Private Investment in Public Entity), stricter disclosure requirements compared to before, and the low interest rate environment, this market is different than the dot-com era.

Regardless, bubbles aren’t always that bad: look at the Amazons and Ciscos that are children of the dot-com financings, the dramatic cost drops for clean energy despite its cycles, and the emergence of U.S. leadership in shale gas despite numerous bankruptcies.

A revolution in our nation’s mobility and infrastructure systems is underway and must be if we want to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. In our battle against climate change, the current and future administrations should turn this financial innovation into an ally rather than see it as an enemy.

This insight is a part of our Undergraduate Seminar Fellows’ Student Blog Series. Read work from other students and learn more about the Undergraduate Climate and Energy Seminar.

Sinan Onukar

Undergraduate Seminar FellowSinan Onukar is a senior undergraduate student studying Finance and Business Analytics at the Wharton School of Business. Onukar is also a 2021 Undergraduate Seminar Fellow.