Will the Dakota Access Pipeline be the Next Keystone?

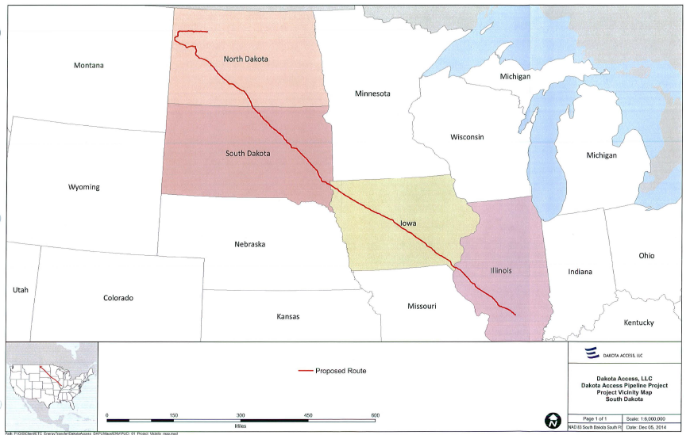

In North Dakota, environmentalists have been fighting hard and winning big on the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline. The 1,200 mile pipeline would cost $3.7 billion and would pass through North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois, caring 450,000 barrels of Bakken crude oil a day to the Gulf of Mexico.

Environmentalists claim this pipeline would be equivalent to adding 21 million more cars to the road. They also assert it would unnecessarily threaten drinking water supplies and violate native tribal grounds. Conversely, supporters of the pipeline see it as critical to producing the domestic energy needed to close the gap between what the U.S. produces and consumes. Supporters also cite reports that the pipeline could create anywhere from 8,000 to 12,000 local jobs during the construction phase and would “translate into millions in state and local revenues during the construction phase and an estimated $129 million annually in property and income taxes.”

Despite the outlined benefits of the project, opposition is well organized and just won a major victory. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe requested a preliminary injunction to stop construction on the grounds that the pipeline would cut through “areas of great historical and cultural significance for the Tribe.” Last week, minutes after a federal judge denied this request, three federal agencies announced in a joint statement that they would effectively halt construction of the most contested section of the pipeline.

If this back and forth sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Remember the Keystone XL Pipeline—a proposed pipeline rejected by President Obama in 2015 that would carry oil sands from Alberta, Canada to Nebraska? Environmentalists against the Dakota Access Pipeline are citing the same concerns—drinking water threats and native land violations.

Native American tribes are powerful constituencies in both high-profile pipeline fights. In the Dakota Access case, however, the involvement of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe takes this from an issue solely concerned with energy and the environment to an issue involving more complex relations between injustice and inequity of marginalized communities.

Native Americans are uniquely positioned to advocate for the preservation of land and community—yet, they are not always against energy infrastructure projects. In the Pacific Northwest, when weighing the impact of the proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal that would ship Powder River Basin coal to Asian markets, there were mixed reactions:

“The potential expansion of coal exports elicits differing opinions among tribes and communities here. What may be an environmental or public health imposition for one is seen as a desperately needed opportunity for another. The coal industry, for example, argues that exports could inject welcome economic activity into struggling Northwest towns and reservations.”

The revenue generation and jobs from a potential energy infrastructure project sometimes outweighs the concern for preservation of Native Land.

Even with the injunction last week, this fight is far from over. The Dakota Access Pipeline will remain in the news and, similar to the Keystone Pipeline, will act as a litmus test against which politicians will have to prove their commitment to the environment and Native Americans or to energy security. As pressure mounts, one wonders if Dakota Access is inevitably headed toward the same lengthy demise as its predecessor.

Mollie Simon

Senior Communications SpecialistMollie Simon is the senior communications specialist at the Kleinman Center. She manages the center’s social media accounts, drafts newsletters and announcements, writes and publishes content for our website, and regularly posts to our blog.