Who Buys Down the Risk When Federal Funding Recedes?

Federal investments have jump-started hundreds of clean energy projects—but political uncertainty now threatens momentum. As DOE demonstration dollars wane, who carries the risk? A new de-risking rubric shows how technical, financial, and social data can keep first-of-a-kind technologies financeable and scalable. The energy transition isn’t only about innovation—it’s about who holds the risk when politics shift.

When Federal Catalysts Stall

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) represent the most significant public investment in U.S. clean energy history. Thousands of projects, spanning carbon capture, hydrogen hubs, and advanced manufacturing, are now underway across federal agencies.

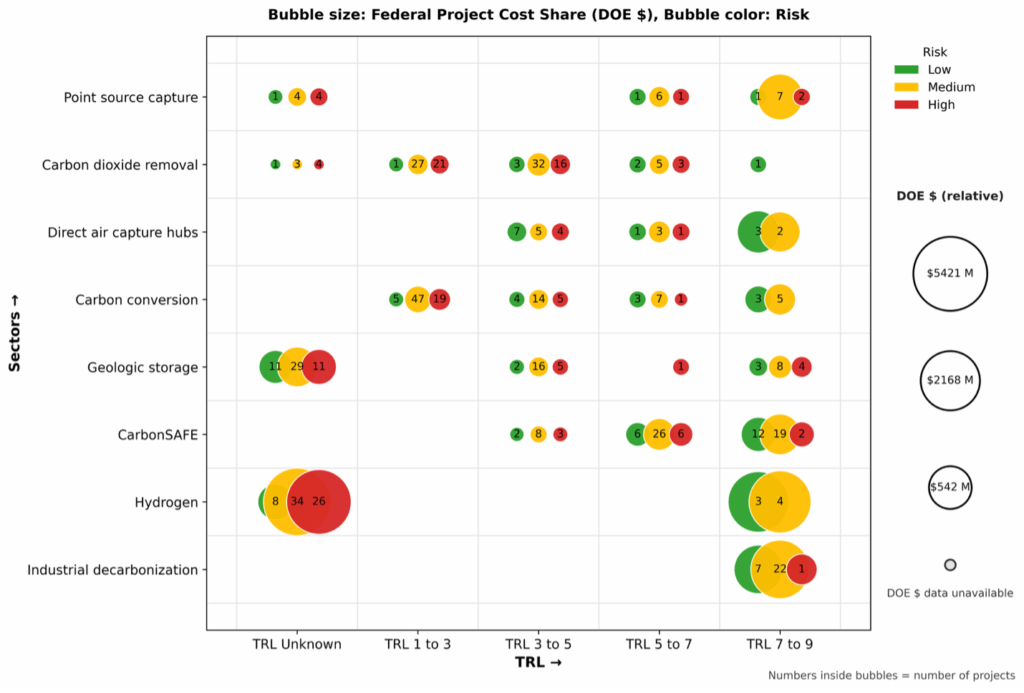

Within this landscape, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has awarded more than 500 projects that aim to commercialize first-of-a-kind (FOAK) technologies, demonstrating deep industrial decarbonization. But as political uncertainty grows and some projects face delays or cancellations, one question looms: who buys down the risk when federal funding recedes?

Our De-Risking Rubric offers a structured way to assess where risk resides—technical, financial, and social—and how the private sector can share responsibility for sustaining progress.

Geography of Risk

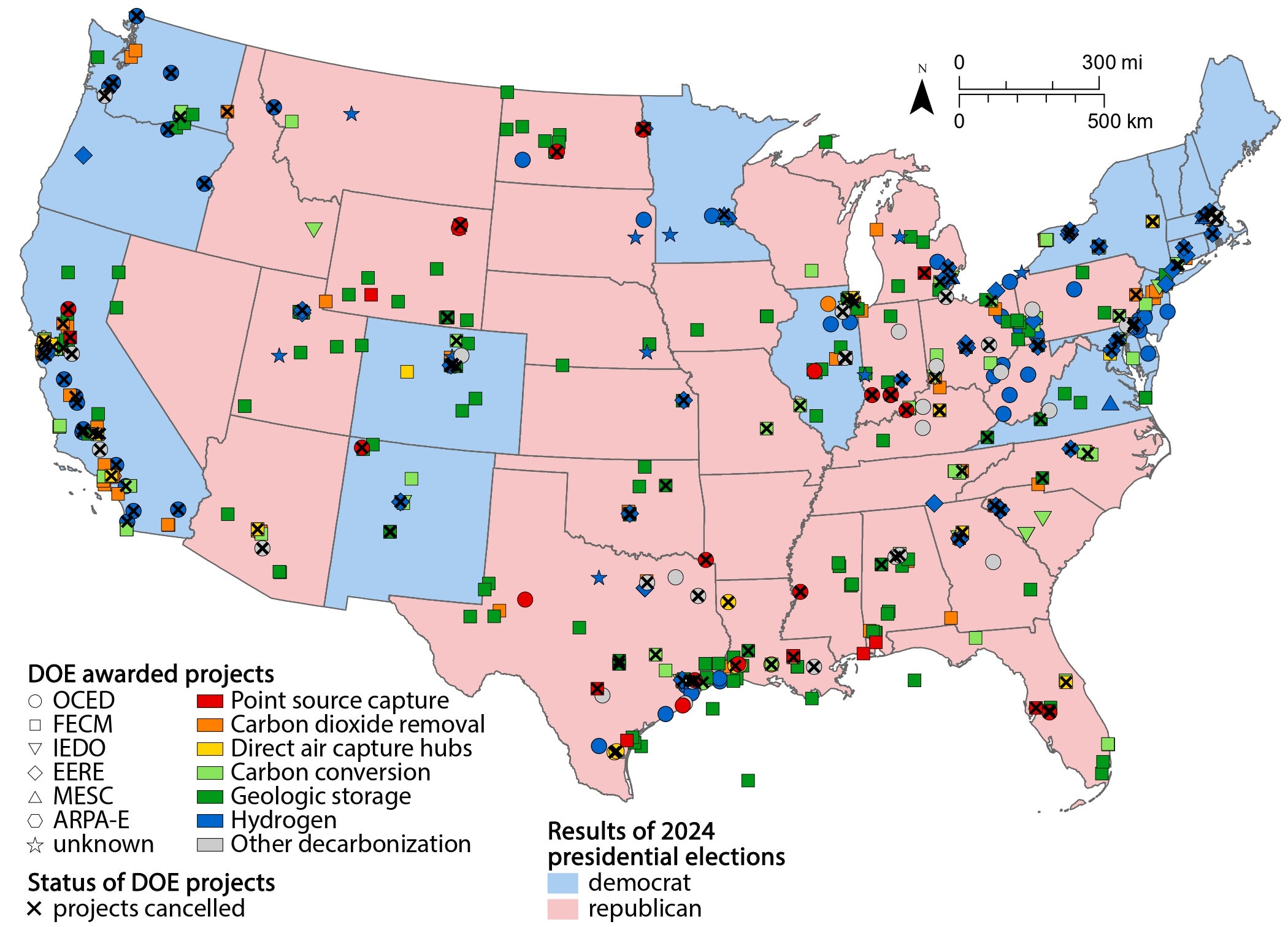

Public investment is reshaping the industrial map in surprising ways. Roughly 85 percent of IRA-related clean-tech dollars—and 60 percent of DOE demonstration projects—are located in states that voted Republican in the last presidential election.

These include Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama—regions historically tied to fossil energy but rich in infrastructure, workforce, and land for large-scale deployment. Meanwhile, blue states such as California, New York, and Massachusetts continue to lead in research, procurement standards, and market-shaping policies like Buy Clean.

Together, red and blue states are creating a geographically diverse ecosystem of risk reduction and opportunity.

The De-Risking Rubric: Technical, Financial, and Social Dimensions

The De-Risking Rubric evaluates projects along three interlocking axes:

- Technical risk declines when projects collect and share real-world performance data—cost, uptime, and energy use—creating a factual base for replication.

- Financial risk falls when projects meet schedules and budgets, giving lenders and off-takers confidence to finance “next-of-a-kind” deployments.

- Social risk diminishes when communities and workers are engaged early, permitting is predictable, and benefits are transparent and measurable.

Across all dimensions, the goal is the same: build the evidence needed to reduce uncertainty and lower the cost of capital. Shared data transforms isolated demonstrations into an investable market class, accelerating replication and attracting private investment.

Public to Private Data Bridge

As IRA and BIL funds flow, the next challenge is ensuring projects remain financeable and insurable after federal dollars expire. Investors now prize one thing above all: transparency. They need consistent, verified data comparing projected and actual costs, schedules, and operations. Put simply, the FOAK gap is a data gap. Even projects that lose federal support can still de-risk their sector by disclosing performance metrics that refine investor and insurer models.

Red and Blue States: Complementary Risk Ecosystems

Red and blue states play different but complementary roles:

- Red states provide industrial infrastructure, labor, and permitting conditions favorable to large-scale deployment.

- Blue states generate early markets, innovation ecosystems, and policy frameworks that sustain demand for low-carbon products.

Federal dollars catalyze innovation, but state and local governance anchor deployment—each reducing risk in complementary ways.

Toward Durable, Insurable Markets

The energy transition ultimately depends on projects that can stand on their own—technically, socially, and financially. Programs that generate verifiable, high-quality data will continue to attract insurers and financiers as public funds wane.

De-risking, in this sense, is the bridge from federally backed pilots to market-driven deployment. When projects demonstrate not only innovation but reliability, they earn capital-market confidence—and that confidence sustains long-term decarbonization.

Conclusion

America’s energy transition is not a story of partisanship but of risk management. Federal investments have catalyzed thousands of projects, but the lasting challenge is building systems that endure beyond political cycles.

Understanding and mitigating technical, financial, and social risk is essential to a durable energy economy. Mastering that de-risking bridge will determine whether the United States leads the next industrial revolution or watches it happen elsewhere.

Katie Harkless

Senior FellowKatie Harkless is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center. She recently served as a senior leader at the U.S. Department of Energy, overseeing the $6.3 billion Industrial Demonstrations Program under the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations.

Shrey Patel

PhD Candidate, Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringShrey Patel is a PhD candidate in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on the integration of carbon dioxide removal with low carbon energy sources.

Hélène Pilorgé

Research Associate, Clean Energy Conversions LabHélène Pilorgé is a research associate with the University of Pennsylvania’s Clean Energy Conversions Laboratory. Her research focuses on carbon accounting of various carbon management solutions and on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping for responsible deployment of carbon management.

Makenna Damhorst

Undergraduate Seminar FellowMakenna Damhorst is a third year student in earth and environmental science. Damhorst is also a 2025 Undergraduate Student Fellow. She conducts research with the Clean Energy Conversions Laboratory.

Jennifer Wilcox

Presidential Distinguished ProfessorJen Wilcox is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering and Energy Policy. She previously served as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the Department of Energy.