Universities as CDR Launchpads in Kenya and Brazil

With COP30 in Belém approaching, demand for carbon removal is rising—and so is scrutiny. Kenya and Brazil can capture the opportunity by turning clean grids and agricultural expertise into high integrity projects and local jobs, if universities rapidly train talent to design, verify, and govern CDR across public and private markets.

Carbon markets are opening new channels of climate finance for developing countries—and present a chance to turn rising global demand for carbon removal into high‑quality local jobs. Under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement, countries are signing bilateral deals for internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs).

For example, Kenya signed with both Switzerland and Sweden in early 2025. Simultaneously, companies are seeking to meet climate targets. In both arenas, carbon dioxide removal (CDR) can play a strategic role—if nations build the talent to design, verify, and govern it.

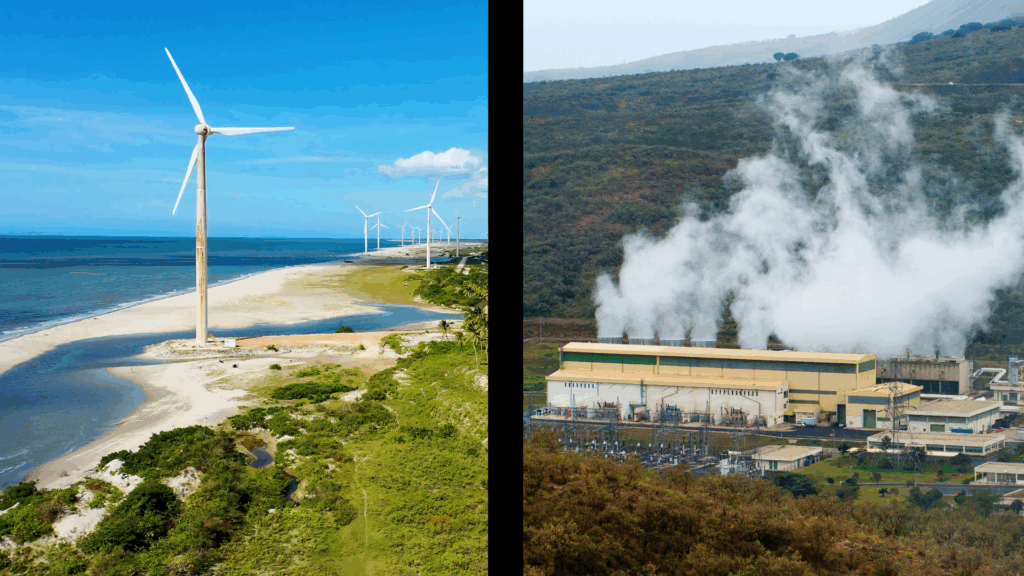

CDR aligns with domestic development goals in Kenya and Brazil. Both countries prioritize low‑carbon industry and green manufacturing, objectives that pair with carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) and with direct air capture (DAC). These technologies perform best on clean power, and both countries already generate over 80% of their electricity from renewables.

Agriculture and food security are also key priorities, and soil‑based CDR options like biochar and enhanced rock weathering (ERW) can improve soil quality and boost yields on degraded soils. Companies can also make progress by insetting CDR in supply chains—for example, by applying ERW to commodity crops.

Despite these opportunities, past land‑use CDR projects often produced poor outcomes, fueling skepticism about carbon credits. In June 2025, Brazilian federal prosecutors sought to repeal a 12‑million‑credit contract (≈$180 million), citing lack of consultation and legal concerns. In Kenya, the Northern Kenya Rangelands Carbon Project was suspended due to insufficient public participation.

These cases underline the need for domestic rules and cross‑disciplinary experts to deliver projects that are technically sound, socially legitimate, and legally compliant. Core principles include free prior and informed consent (FPIC), clear land tenure, transparent benefit‑sharing, host‑country authorization, independent monitoring with uncertainty accounting, and accessible grievance mechanisms.

Foundations for better outcomes are emerging. Kenya’s 2024 Climate Change (Carbon Markets) Regulations establish authorization pathways for voluntary and compliance transactions and require Community Development Agreements plus documented FPIC for community‑land projects. Brazil also established a Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading System (SBCE in Portuguese) in 2024, including a legal basis for reduction/removal certificates.

A domestic workforce is needed to interpret these frameworks, operate registries, and ensure fair benefit distribution. Universities should train graduates to navigate these agreements—e.g., host‑country authorization, Article 6 accounting, and the voluntary–compliance interface—by integrating CDR into environmental law, policy, and economics courses.

A strong science and engineering pipeline is equally critical for technology implementation and long‑term environmental monitoring. Engineers can adapt CDR technologies to local conditions, optimize performance for regional energy systems, and build robust measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV).

Because CDR touches energy, agriculture, and manufacturing, talent cultivated for CDR strengthens broader decarbonization. Without a domestic technical workforce, countries risk dependence on foreign consultants and imported technologies—foregoing local jobs, innovation, and the ability to set standards that reflect national priorities.

Universities can move quickly to train this workforce. Rather than creating new degrees, CDR can embed into existing courses: a cross‑cutting “CDR 101” in environmental engineering or economics; a soil science lab on biochar and ERW sampling, pH testing, and quality control; and CDR case studies in finance and accounting.

Early exposure to CDR career paths helps students move into analyst and junior engineering roles in project development, MRV, policy, and supply‑chain decarbonization, seeding the workforce needed to meet rising demand.

CDR offers a unique chance to align development and climate mitigation but realizing that potential requires deliberate investment in human capital: policymakers, lawyers, economists, scientists, and engineers who meet the technical and social bar for high‑integrity projects. With COP30 in Belém on November 10–21, CDR literacy must scale with opportunity. Kenya and Brazil’s universities can lead.

Suria Gopal Crabtree

FellowSuria Gopal Crabtree is a fellow at the Kleinman Center. Her research interests include the intersection of energy access and climate change mitigation.

Abby Lunstrum

Research Associate, Clean Energy Conversions LabAbby Lunstrum is a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania. She holds a PhD in Geology from the University of Southern California.

Jennifer Wilcox

Presidential Distinguished ProfessorJen Wilcox is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering and Energy Policy. She previously served as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the Department of Energy.