How Inequity Across the U.S. Has Unjustly Worsened the Impacts of Extreme Heat

Historical discriminatory policies in Philadelphia and cities across the nation have placed minority and low-income communities at a higher risk of being harmed by extreme heat. Local governments must invest in these communities to work towards a more just society.

Heat waves are becoming more frequent and intense across the United States, placing stress on the nation’s energy systems. Heightened temperatures decrease the carrying capacity of power cables and reduce the efficiency of energy generation technology, such as solar panels and natural gas turbines. Simultaneously, they spur increased usage of energy for air conditioning.

This places communities affected by extreme heat at a higher risk for blackouts, which can be remarkably dangerous during a heat wave event. In fact, the leading cause of weather-related deaths is extreme heat, as extended exposure to high temperatures increases the risk of developing illnesses, such as heat stroke, and exacerbates other existing ailments, such as heart disease or diabetes.

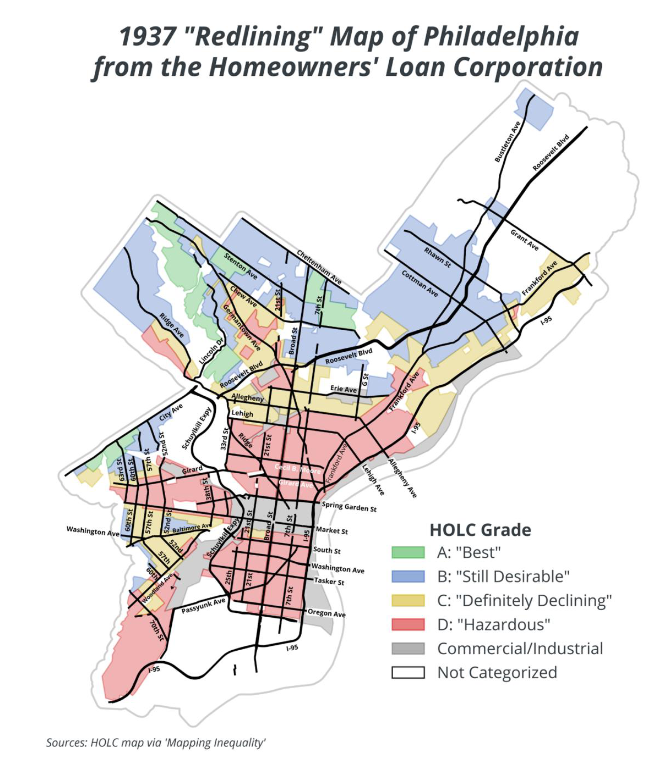

While extreme heat, which occurs largely in cities, poses an issue for all residents, it tends to have a disproportionate impact on historically marginalized communities. Areas that are home to lower-income families and communities of color are more likely to experience extreme heat. This reality stems from the historical practice of redlining, in which the federal government categorized neighborhoods with large minority and immigrant populations to be “undesirable” for real estate investment from the 1930s until the 1960s. Consequently, lenders largely denied mortgages to residents of these communities, impacting their ability to develop generational wealth through property ownership. This has created clear wealth and racial divisions throughout urban areas. The effects of these divisions are still seen today, as previously-redlined areas are less commonly found to have houses with air conditioning, and contain significantly fewer instances of heat-mitigating infrastructure, such as green areas, and are more likely to have a high density of heat-absorbing buildings and roads. A 2020 study that surveyed 108 cities found that 94% exhibited elevated surface temperatures of up to 12.6°F within neighborhoods previously categorized as “high-risk” for investment.

Philadelphia has faced the repercussions of these inequitable policies. An analysis conducted in 2023 found that more than 900,000 people in Philly live in areas with temperatures artificially inflated by at least 8°F due to pavements and roofs. Hunting Park, a neighborhood in North Philadelphia which is home to predominantly Latino and African American residents, can reach temperatures 20°F hotter than other areas in the city. This is due to a historical lack of funding for infrastructure to mitigate extreme heat. While the average percentage of land covered by tree canopies throughout the entire city is about 20%, Hunting Park has only 9% tree coverage. Additionally, a 2020 survey of the neighborhood found that only 100 out of 563 residents had air conditioning within their homes. Intensifying the issue, a $500,000 grant from the United States

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to increase tree density, distribute air conditioning units, and advance extreme heat education programs in Hunting Park was canceled by the federal Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) earlier this year. Several neighborhoods in the city face similar challenges. For example, lower-income residents around Philly tend to also have relatively dark roofs, leading to higher temperatures within homes.

To combat heat inequity, Philadelphia announced the Philly Tree Plan in 2023, a 10-year plan for devoting resources to developing the city’s urban forest. A significant goal of the project is to increase citywide tree canopy coverage to 30%, which involves prioritizing areas that have fallen behind with green, heat-mitigating infrastructure. Also, the Energy Poverty Alleviation Strategy was released in 2024 to promote the inclusion of vulnerable communities in the local clean energy transition. As part of this, Philadelphia has explored the potential of reflective roof coatings in minimizing extreme heat in disproportionately affected households. In

high-temperature conditions, traditional roofing can reach temperatures of up to 150°F; however, reflective roofs offer a simple way to lower the impact of extreme heat on homes.

Combating extreme heat requires thoughtful solutions that account for the historical mistreatment of traditionally underserved communities. The growing threat of heat waves demands an urgent nationwide commitment to environmental justice through infrastructure investment in neighborhoods most affected by decades of marginalization.

Cristian Solano

Kleinman Center Research AssistantCristian Solano is a research assistant at the Kleinman Center. He is a junior in the School of Engineering and Applied Science studying Materials Science and Engineering with an Energy and Sustainability Concentration, alongside Economics.