The Hubbub About Gas Storage Levels

Explore the impacts of the U.S. heading into the winter peak gas demand season with the lowest storage inventories since 2005. The short version, it's all about prices.

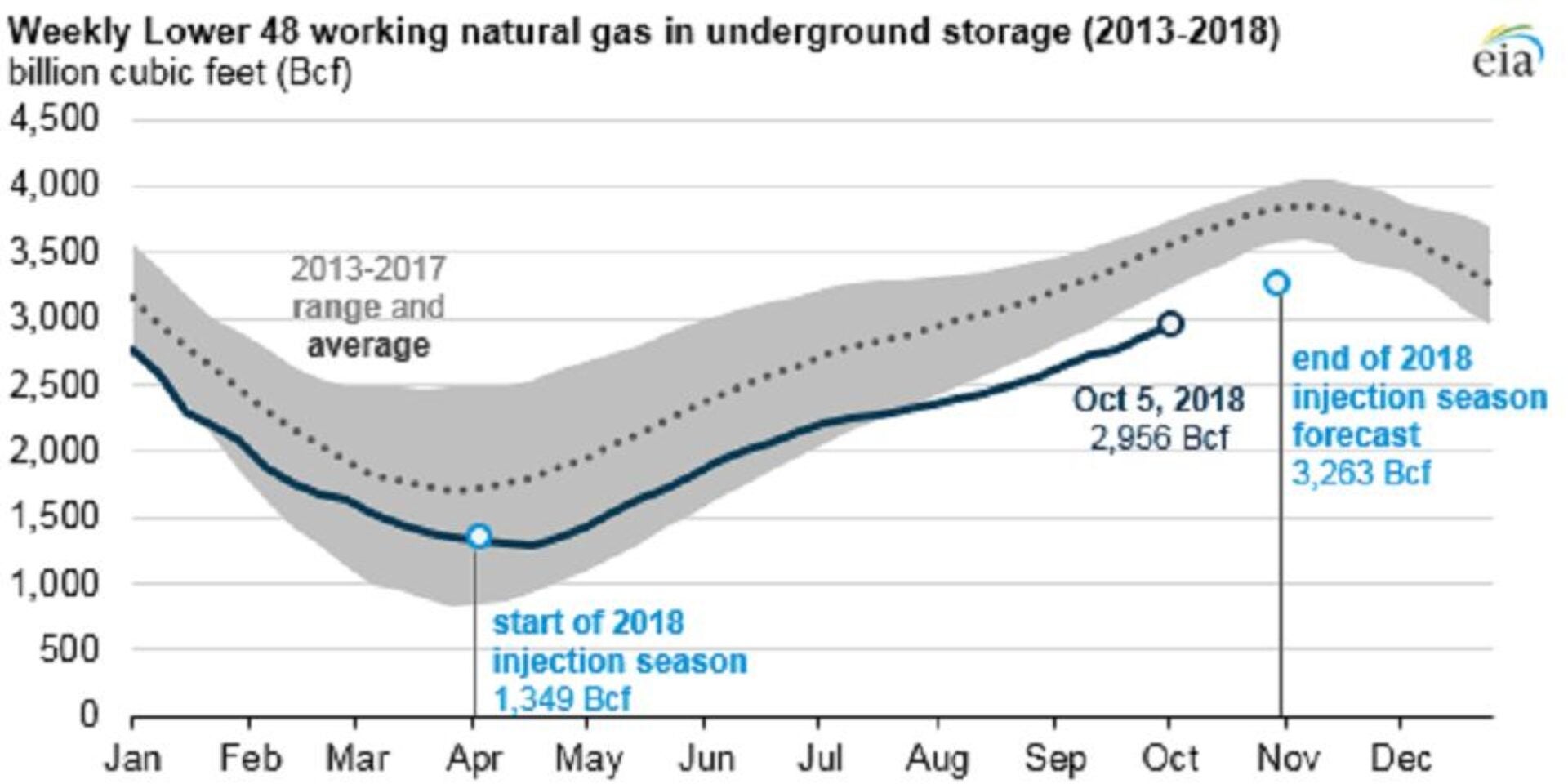

Last Friday, the U.S. EIA published data showing natural gas storage inventories for this time of year are at their lowest levels since 2005, and well below the 5-year rolling average range. I’ve been seeing a lot of hubbub (EIA even released a nifty gas storage dashboard in early September) about low gas storage levels recently, so let’s see what all the fuss is about?

Gas Storage Basics

Natural gas is primarily stored in underground, geologic formations (e.g. aquifers, depleted gas fields, salt taverns) or, to a lesser extent, liquefied natural gas (LNG) tanks. Gas is “injected” into storage at times of lower demand (e.g. spring, summer, fall) and withdrawn from storage during periods of high demand (i.e. winter). These stockpiled volumes help bridge the gap between gas consumption and production, when consumers increase gas use in cold weather periods to heat homes and businesses.

Lower than average gas storage levels heading into the peak demand season raise questions about adequacy of supply, and higher prices. And, since gas demand has increased significantly with the rise of U.S. shale development, the economy may be more vulnerable to price volatility.

So, Why Are Storage Levels So Low?

EIA attributes these low levels to significant withdraws in January 2018 during an extended cold spell, a delay to the start of the injection season as cold temperatures persisted through April 2018, warmer summer temperatures (i.e. increase air conditioning), growth of gas exports, and several other factors. Others note high fall temperatures have increased power sector gas demand to record levels for October, potentially diverting some gas supplies otherwise bound for storage.

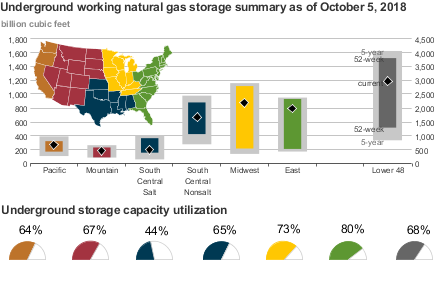

In fact, gas storage levels are below five-year average ranges for almost every storage region, except the Mountain region. (see the graphic above)

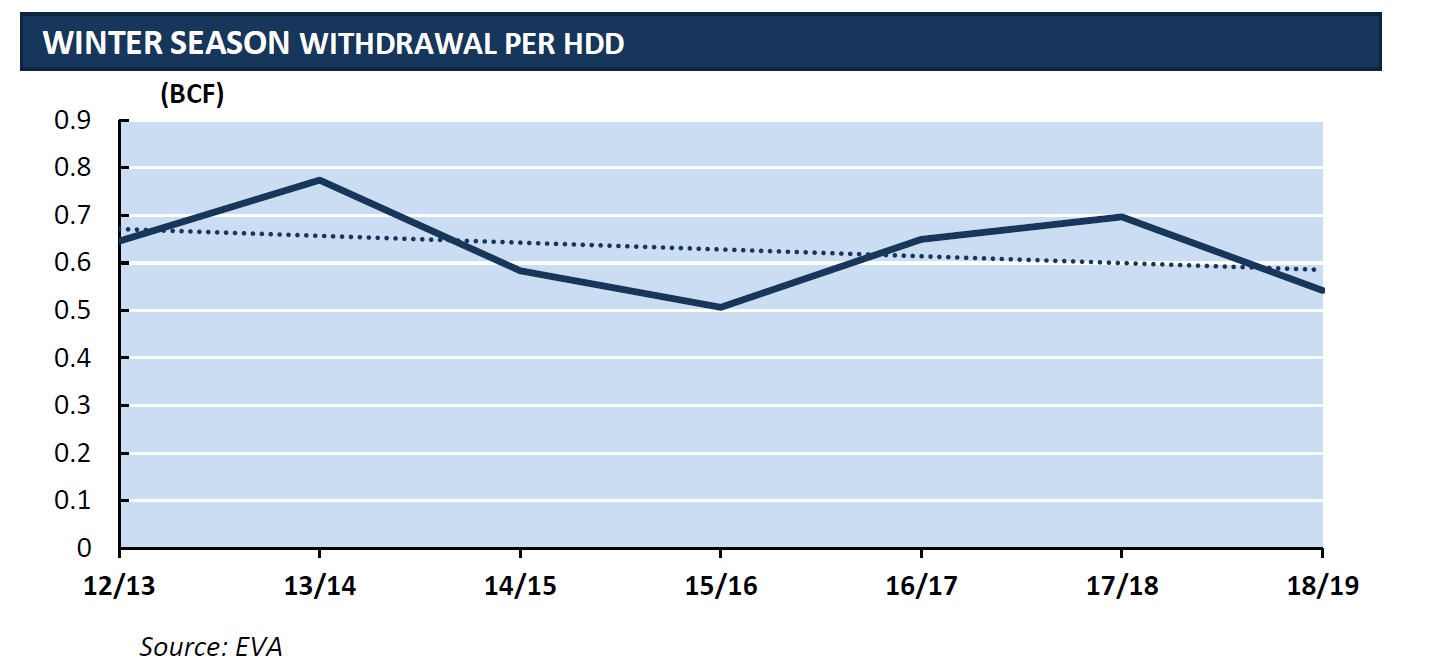

EIA believes some of the storage inventory decrease may be due to new pipeline capacity coming online, increasing the ability for producers to bring product to market and decreasing reliance on storage. Analysis commissioned by the Natural Gas Supply Association (NGSA) also points to reduced winter storage withdraws per heating degree day, bolstering the notion that the system has become less reliant on storage. (see graphic to the right)

Is This a Big Concern?

As mentioned, most of the concern about low storage levels relates to rising prices and price volatility, especially as temperatures dip.

Natural gas production is at record high levels with gas production forecasted to be up 10% compared to last winter. And, production doesn’t experience big seasonal fluctuation like demand, but can be temporarily shut down by freeze-off events in very low temperatures. However, consumption and peak demand are up at record levels too.

NOAA’s winter weather forecast generally indicated the 2018-2019 winter temperatures would be similar to last year’s. NOAA also predicts an El Nino pattern may develop, which may increase the risk of warm or cold extremes in some areas of the country (see this graphic from NOAA). However, extreme cold snaps are unpredictable.

Concern levels may be different for each region of the U.S. For example, areas of the northeast and mid-Atlantic are highly dependent on gas for both space heating and electric power, potentially increasing vulnerability to supply issues and price spikes. For example, gas plants that don’t have firm gas contracts with low-cost supply are particularly vulnerable.

At this time last year, Henry Hub spot prices were $2.89/MMBtu. Prices have risen steadily over the past month driven by storage levels, and are now around $3.40/MMBtu. EIA is forecasting an 8% increase in the Henry Hub spot price this winter, due to low gas inventory levels.

Implications

Most likely, the gas industry can reliably manage these low storage levels, but prices will tick upwards and there may be some location-specific price spikes during cold snaps.

Higher commodity prices will improve the financial outlook for some gas production companies.

On the other hand, increased coal (and oil) power plant dispatch will occur in cold temperatures, if/when gas prices spike. This is driven by least-cost dispatch principles (i.e. economics), not decreased reliability or resilience of the gas system. However, in today’s politically-charged energy policy landscape, count on such incidents to be followed by calls for coal bailouts.

Christina Simeone

Kleinman Center Senior FellowChristina Simeone is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and a doctoral student in advanced energy systems at the Colorado School of Mines and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a joint program.