Introduction

Pennsylvania is the largest natural gas producing state in the U.S. that does not impose a severance tax on new or current unconventional gas wells. Instead, as of 2012, gas producers pay an annual impact fee. In his 2015-16 budget, Governor Tom Wolf proposed a severance tax on the gas industry that is estimated to yield significant revenues to the state. Though the GOP-controlled legislature has since submitted a budget eliminating all the proposed taxes, the specific details of the governor’s proposal are well worth reviewing. With the governor having vetoed the GOP’s budget, the severance tax stands to be a major point of contention moving forward. The Kleinman Center has prepared this digest explaining the basics of the impact fee and the proposed severance tax to help explore this issue with the public.

The Impact Fee

Act 13 was signed into law by former Governor Corbett with House Bill 1950 on Feb. 14, 20121. The Act authorizes the imposition, collection, and distribution of an impact fee on the development of unconventional natural gas resources.

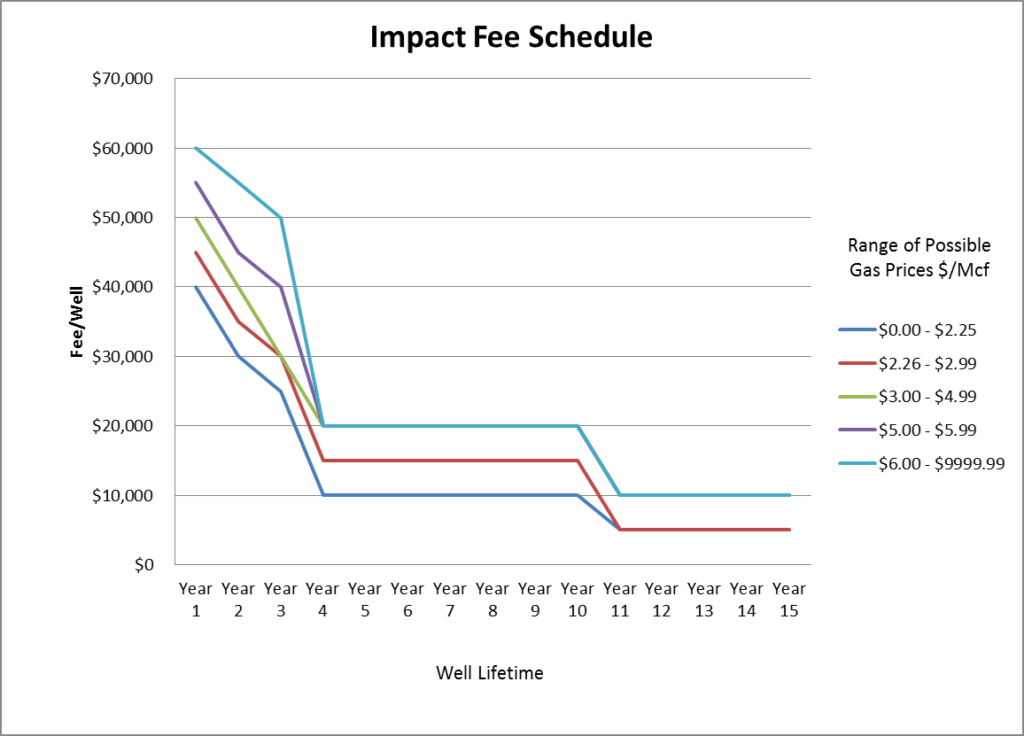

The impact fee in Act 13 is a set annual fee producers pay for each well ‘spud’— industry term for the commencement of drilling at a well site — during the year. The fee is determined by the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission (PUC) based on a schedule established in Act 13. The schedule lists the fees to be paid per well for the first 15 years of production and is based on the average price of natural gas on the NYMEX. The schedule can be adjusted to reflect upward changes in the Consumer Price Index provided the total number of spuds in a given year exceeds the number in the prior year2.

In 2013, gas production companies paid $50,000 for each spud at an average natural gas spot price on the NYMEX of $3.73/million BTUs3. Smaller vertical wells were charged only $10,000. Wells which do not produce significant amounts of natural gas (under 90,000 cubic feet/day) are not assessed an impact fee. For 2014-15, the state collected approximately $225 million in impact fees from all active well sites4.

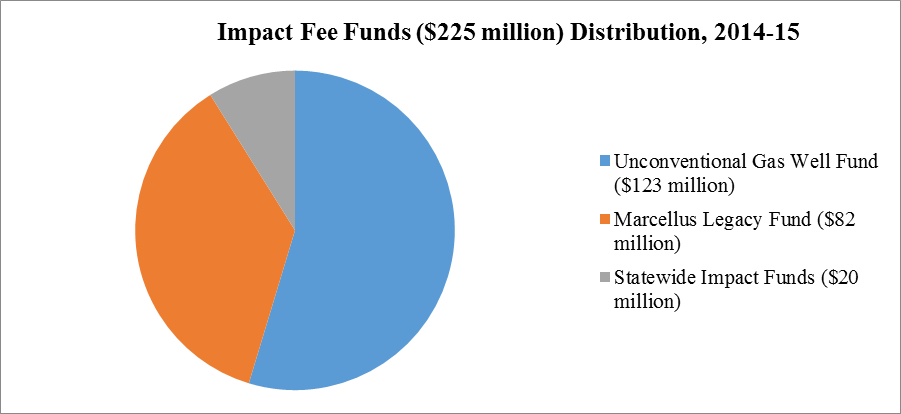

Each year the PUC establishes the impact fee rate based on the NYMEX natural gas price. The PUC then collects the funds and distributes them to counties, municipalities, and the state. About $20 million is allocated to various state agencies, including the Pennsylvania Utility Commission and the Department of Environmental Protection, to offset the statewide impact of drilling. After this initial allocation, the remaining funds are distributed to the Unconventional Gas Well Fund and the Marcellus Legacy Fund. This breakdown is illustrated in Figure 2:

After the $20 million for state agencies, all revenue from the impact fee is distributed to the two funds for counties and municipalities who host drilling activities. Money from the funds is spent by counties and municipalities for specific environmental mitigation projects and to improve or maintain infrastructure in their jurisdictions as outlined in Act 13.

The Unconventional Gas Well Fund received the largest chunk of the revenues from the impact fee at nearly $123 million in 2014-15. From this total, $5 million is set aside for the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency to increase affordable housing for low and moderate-income families in counties or municipalities with unconventional wells as prescribed in Act 13. The rest is allocated to counties with unconventional wells according the fraction of total state wells located in the county. These funds must be used on infrastructure initiatives aimed at reducing the impact of natural gas extraction in those counties, and includes projects such as roadways, bridges, storm water management and sewer systems, as well as emergency preparedness and environmental preservation and reclamation efforts. Counties and municipalities must report these expenditures to the PUC to verify they were used on approved projects.

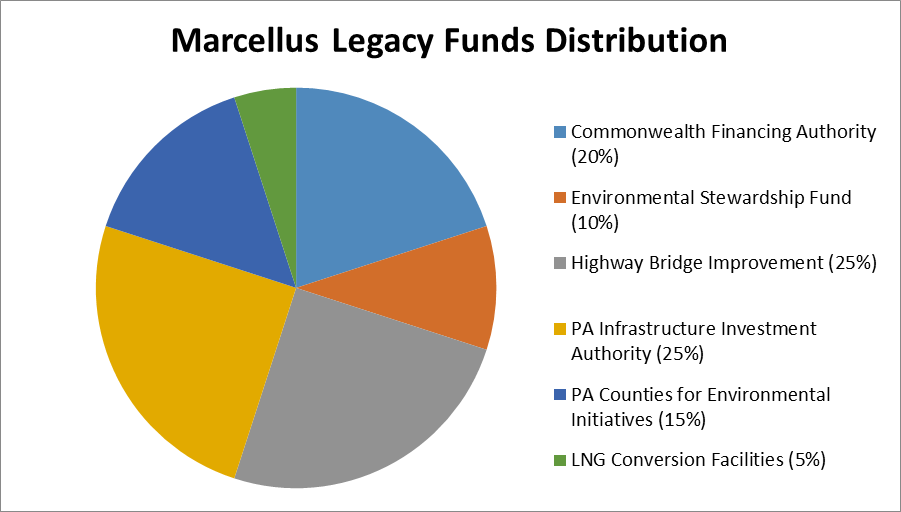

Finally, the Marcellus Legacy Fund received approximately $82 million in impact fees collected in 2014-15. This funding must be spent according to the categories illustrated in Figure 3 below:

As should be clear from the above funding breakdowns, municipalities and counties have the potential to greatly increase revenues by encouraging well development within their borders. A more detailed description of the funds collected by the PUC, as well as the various allocations of those funds can be found in the Act 13 impact fee report published annually by the PUC.

Severance Tax Proposal

To meet Governor Tom Wolf’s educational goals for the Commonwealth, the governor proposed the Pennsylvania Education Reinvestment Act in his 2015-16 budget. This Act aims to raise $2 billion in revenue for public education by, among other things, imposing a tax on the extraction of natural gas within the Commonwealth5. This tax is modeled after the severance tax in neighboring West Virginia which, like Pennsylvania, has seen a recent boom in production of natural gas from unconventional drilling6. This severance tax would replace the current impact fee discussed above.

*In calculating the average market price, the DEP will use the weighted average price per thousand cubic feet for all major distribution hubs in Pennsylvania for the three months prior to the quarter the tax will be imposed for.

**Several different bills have been introduced regarding a severance tax following Governor Wolf’s announcement on March 3, with rates varying depending on the bill from 3.5% with a 3.5 cent production fee to 8% with no production fee. However, SB 116 is the bill intended to be a part of the Governor’s Proposal and thus the one discussed here.

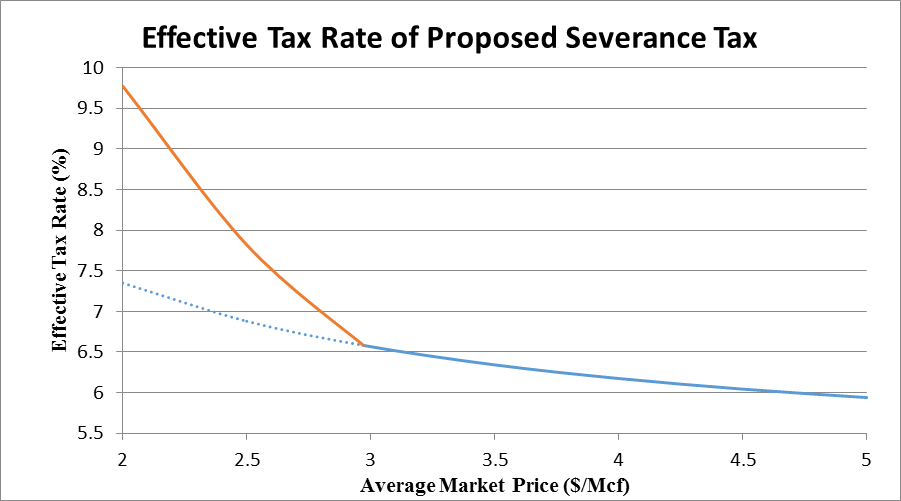

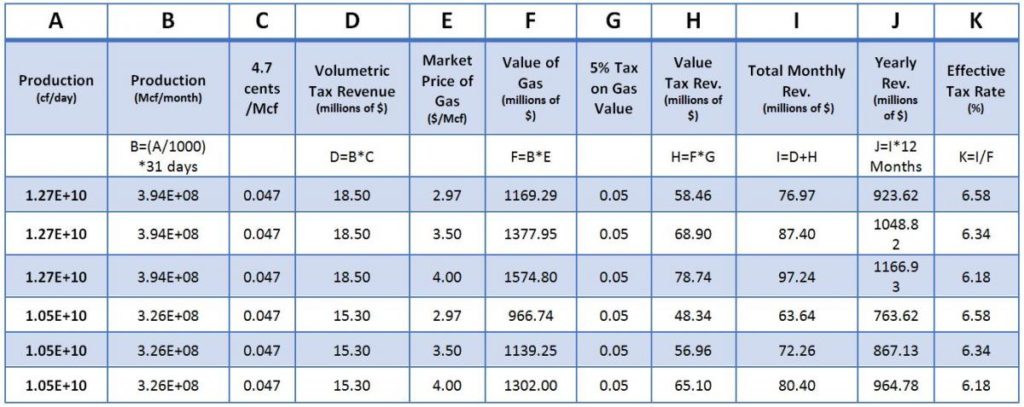

The tax proposal was officially introduced by Senator James Brewster (D) as part of SB 116 and would impose a 5% charge on the average market price* of natural gas extracted in Pennsylvania, plus 4.7 cents per thousand feet of extracted volume.** The minimum natural gas price allowed in calculation of the tax would be $2.97/thousand cubic feet. With both a flat volume fee and a percentage value tax, the severance tax would act in such a way that low gas prices result in a higher effective tax rate on each unit of gas extracted, while high prices will decrease the effective rate. This trend is more clearly shown in Figure 4 below, which demonstrates the effective tax rate as a function of the average market price. When gas prices fall below $2.97/thousand cubic feet, the effective tax rate quickly increases, as producers would be taxed on the basis of a price higher than the actual price they will get on the market.

It is important to note a stipulation in the law forbids the natural gas companies on whom the tax is imposed, from passing on these fees to the land owners or resource owners they have contracts with.

To more clearly see how this tax works, we provide an example:

In February of 2015, gas production was approximately 12.7 billion cubic feet per day. Assuming the minimum price of $2.97/Mcf is to be implemented (current prices are below this level) this would mean $18.50 million in tax for the flat 4.7 cents fee, as well as $66.75 million in taxes for the 5% tax on the value of the gas for a grand total of approximately $76.97 million7. If this price and production were to stay constant for the whole year, it would yield an expected $923.62 million in revenue.

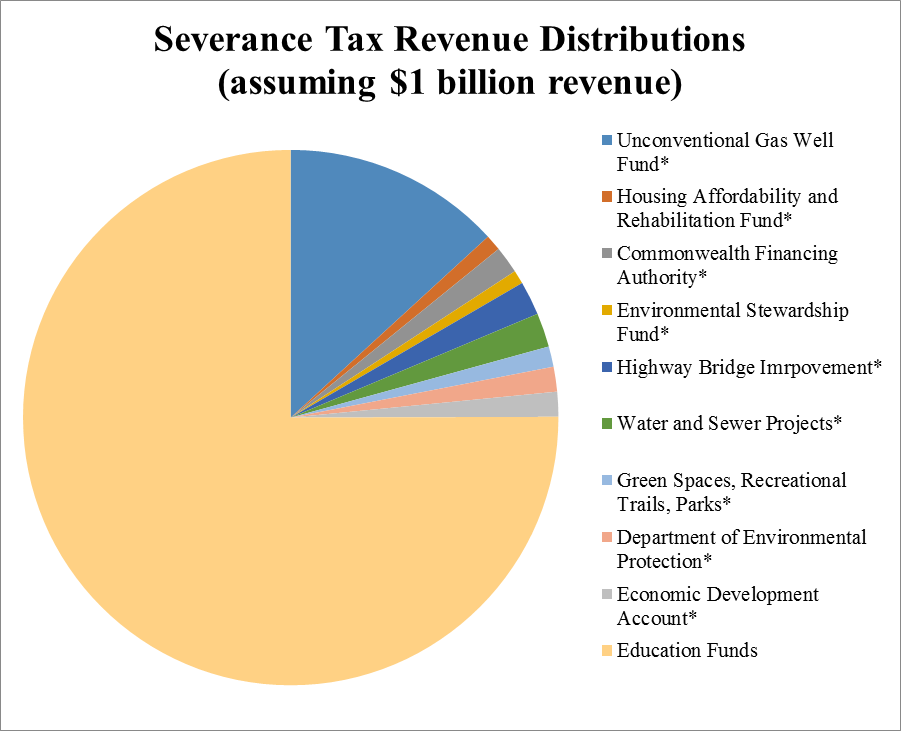

Governor Wolf’s office projects this tax would yield over $1 billion in revenues per year for the Commonwealth starting with the 2016-17 fiscal year, which is consistent with the estimates above. This money would be disbursed according to Figure 5:

As is clear from the chart, education will find a huge source of revenue from this proposed bill, totaling just over $750 million in this one-year scenario with $250 million allocated to various environmental and infrastructure efforts aimed at mitigating the impact of unconventional extraction in Pennsylvania.

Impact Fee – Severance Tax Comparison

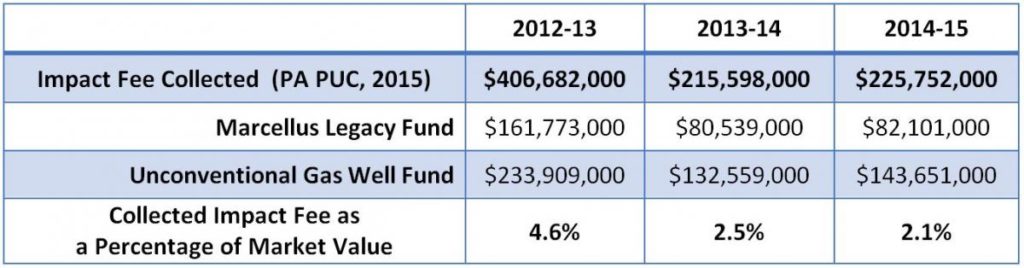

By definition, the impact fee is linked primarily to the number of wells in production and is tied tightly to the drilling of new wells. To make it comparable to the severance tax proposal and have a measure of the tax burden relative to natural gas sales, it is relevant to determine the effective tax rate of the fee.

The Independent Fiscal Office (IFO) calculated an effective tax rate of the impact fee. IFO found that in 2012, the fee paid by the industry was equivalent to 4.6% of the value of the gas produced, while in 2013 and 2014, it was close to 2% due to larger volumes, higher gas prices, and a lower fee per well.

Comparing the rates in Table 1 to those in Table 2, we can see that were the severance tax in place for the most recent year, extraction companies would have paid an effective tax rate more than three times the rate they were charged under the impact fee.

From comparison of the projections in Table 1 and the information in Table 2 it is clear that, all things being equal, the severance tax will bring far higher revenues than the impact fee in almost any probable scenario.

Were the impact fee to match the proposed revenues for the severance tax from the first scenario described in Table 1, the fee would have to rise from a current average of about $27,000 per well to an average of nearly $110,000 per well for the states’ approximately 8,300 producing wells8. Newly spud wells (which have the highest impact fees) would have to be charged significantly more to make up for older wells with lower impact fees, though the fees for older wells would also have to be increased. Given that this represents a four-fold increase on current impact fees, matching potential revenues from the severance tax in such a scenario seems an unlikely proposition.

Furthermore, because the severance tax rate has a built-in balancing effect (rate increase at lower prices, decrease at higher prices) and a minimum average market price, it provides a far more predictable revenue stream for the government than the impact fee, which can fluctuate dramatically depending on the outlook for natural gas and the number of wells spud. Again looking at Table 2, the revenue from 2012-2013 was nearly halved the next year in 2013-2014. Such a large fluctuation is far less likely with the severance tax, allowing the government to more effectively plan multi-year projects such as education funding.

There is also a fundamental philosophical and ideological difference between these two approaches:

- The stated intent of the impact fee legislation is to compensate counties, municipalities, and the state for some of the adverse effects or negative externalities of unconventional extraction. It is not intended to generate general funds or to support programs unrelated to unconventional gas activities.

- The severance tax, however, is intended to be higher so that the funds received by departments and governments from the impact fee can remain constant under the new tax regime, while ensuring enough is left over to pay for the proposed educational initiatives. Whether the funds raised from the severance tax will reach such levels is another topic of contention among the various parties involved.

Therefore, the debate focuses on whether passage of the severance tax offers a clear source of greater, more stable, revenue to the state and local governments and whether the higher tax burden may discourage future investment in Pennsylvania’s unconventional resources by extraction companies9. In the end, this intersection of economic growth, impact mitigation, and priority program funding appropriately moves the discussion from technical analysis to political considerations.

Angela Pachon

Special AdvisorAngela Pachon is a special advisor to the Kleinman Center, in charge of designing and overseeing international programs and teaching. She was previously the Center’s research director.

Dillon Weber

Research AssistantDillon Weber was a research fellow at the Kleinman Center and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania majoring in chemical and biomolecular engineering and economics.

“Act 13 Interactive User Guide,” Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. https://www.act13-reporting.puc.pa.gov/Modules/PublicReporting/Overview.asp

“Impact Fee Update,” Pennsylvania Independent Fiscal Office. February, 2015. http://www.ifo.state.pa.us/Releases.cfm

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. House Bill 1950: “An Act Amending Title 58…” 2012. Pennsylvania General Assembly. Web. Printer No. 3048. [↩]

- “Act 13 of 2012… FAQ,” Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. http://www.puc.state.pa.us/NaturalGas/pdf/MarcellusShale/Act13_FAQs.pdf [↩]

- “Natural Gas Spot and Future Prices (NYMEX),” United States Energy Information Administration. May 2015. http://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_pri_fut_s1_a.htm [↩]

- “Impact Fee Report,” Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. 2014. http://www.puc.state.pa.us/filing_resources/issues_laws_regulations/act_… [↩]

- “2015-2016 Pennsylvania Executive Budget,” Governor’s Budget Office. 3 March, 2015. http://www.budget.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/current_and_pro… [↩]

- “2015-2016 Budget in Brief,” Pennsylvania Governor’s Budget Office. 3 March, 2015. http://www.budget.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/current_and_pro… [↩]

- “Pennsylvania Natural Gas Production Holds Up in February,” Natural Gas Intel. 21 April, 2015. http://www.naturalgasintel.com/articles/102057-pennsylvania-natgas-produ… [↩]

- “Wells Drilled by County,” Pennsylvania Department of Environment Protection. n.d http://www.depweb.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/oil_and_gas/6003 [↩]

- Considine, Timothy J. “The Economic Impacts of the Proposed Natural Gas Severance Tax in Pennsylvania,” 22 April, 2015. http://www.api.org/~/media/files/policy/taxes/2015/economic-impacts-of-t… [↩]