Underground Property Rights for Carbon Capture

As carbon capture projects take off, policymakers must proactively establish legal frameworks and regulations to address potential disputes surrounding access and utilization of subsurface pore spaces for CO2 storage.

Introduction

As of 2022, there were about thirty operational and seventy carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) projects in advanced developmental phases globally. The knowledge gathered over the years from various research and development initiatives and incentives to invest in these decarbonization technologies are notable. However, realizing the potential of CCUS will depend largely on the availability and access to suitable subsurface storage locations. Such access also hinges on whether the land in which the underground storage space is located is owned by the government (public) or private individuals, and subject to third-party mineral estate or leasehold interests to subsurface resources.

This short piece reflects on the implications of property rights governing ownership and access to underground pore spaces for storage and the need for legal clarity for averting or resolving issues that affect the development and operation of CCUS projects.

Capturing CO2 & Access to Storage Sites

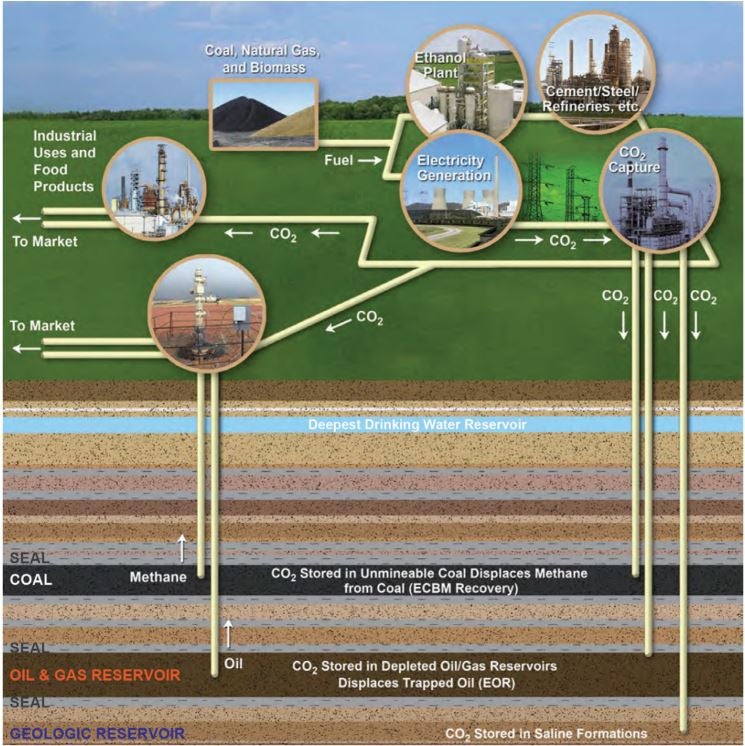

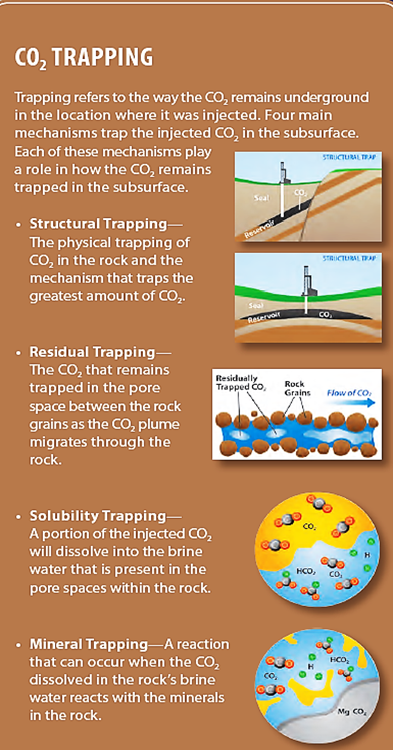

CCUS projects involve capturing CO2 from a source or group of sources and transporting it to carefully selected site(s) for storage in deep underground geologic formations. Potential storage sites include pore spaces found in saline formations, depleted reservoirs, etc. before use, such areas are characterized and determined to be suitable for CO2 trapping and storage.

Source: U.S. DOE/National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), United States Carbon Utilization and Storage Atlas VI 2012 (July 1, 2014).

Property Rights Considerations

The ad coelum doctrine typically applied in common law jurisdictions, presupposes that a landowner owns anything above and underneath his/her land up to the center of the earth. Such property rights would ordinarily extend to subsurface pore spaces and minerals unless ownership and production rights to the minerals have been severed and assigned to another—such as an oil and gas producer. In areas where the mineral estate owner has a dominant incidental right to use the land in the process of finding and producing the minerals (e.g., oil and gas) by operation of law, some important questions come up. For instance, would or should such rights include ownership of the subsurface pore spaces in the process of production? And to what extent do the landowners’ rights to the same subsurface pore spaces take priority? To address these issues, we must consider —whether the land in question is privately owned or government owned;—and also examine the applicable statutory provisions and judicial decisions regarding ownership of subsurface resources in the particular jurisdiction where the land is situated.

States such as North Dakota and Wyoming have enacted laws conferring ownership of such underground spaces in the land “surface” owner. Recently in the case of North West Landowners Association v. State (2022 ND 150, 978 N.W.2d 679) the North Dakota Supreme Court held, among other things, that the surface owners have demonstrated they have a constitutionally protected property interest in subsurface pore spaces and are therefore entitled to compensation when mineral estate holders use such pore space for disposal and storage operations. In Texas, the prevailing view is that ownership of the surface includes ownership of the underground pore space, in the absence of minerals.

Internationally, Canada and Norway are two countries with significant experience and examples of operational CCUS projects and several in advanced developmental phases. In Alberta, the enactment of the Carbon Capture and Storage Amendment Act 2010 helped to clarify issues regarding the ownership and use of subsurface pore spaces and provides that such formations are owned by the Province. The Minister can thus enter into agreements granting the right to inject CO2 into pore spaces for storage purposes. In Norway, the applicable regulations on the exploitation of subsea reservoirs on the continental shelf for storage of CO2 expressly provide that the Norwegian state has the proprietary right to subsea CO2 storage reservoirs, including an exclusive right to the management of these reservoirs.

Conclusion

Going forward, it may be necessary for policymakers to develop and enact legal and regulatory provisions that can help resolve potential disputes regarding access and use of subsurface pore spaces and formations for CO2 storage. Efficiently addressing such controversies will be essential as CCUS projects are being developed and become operational.

Tade Oyewunmi

Assistant Professor, University of North Dakota School of LawTade Oyewunmi is a assistant professor of law and director of the Energy, Environment, and Natural Resources Certificate at the University of North Dakota School of Law. Email: tade.oyewunmi@und.edu.