Are Renewables Alone a Safe Bet to Get U.S. to 50% Clean Power by 2025?

Last month at the North American Leaders’ Summit, the US, Canada, and Mexico announced a goal of achieving 50% clean power across North America by 2025.

Will the US get there with renewables – which for this discussion I’ll limit to solar and wind power – alone?

As this excellent Washington Post article points out, the likely answer is no.

The Summit defined clean power as including renewables, nuclear power, power plants using carbon capture and storage (CCS), and energy efficiency. The share of US electricity production meeting that definition from a generation standpoint currently stands at 33%, with no generation coming from CCS-equipped plants. So, total clean generation needs to grow 50% by 2025.

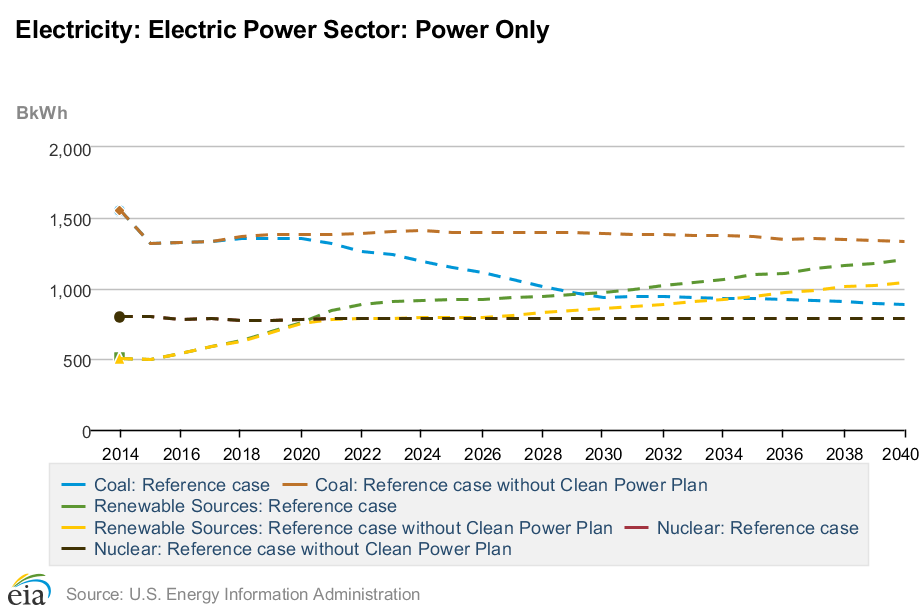

Nuclear power provides a full fifth of US power – and over 60% of the nation’s clean power. While one new nuke is coming online, others will close, and US EIA projects flat generation from nukes. Can renewables scale up and fill the gap in the next 9 years?

The news and numbers around renewable energy are certainly encouraging. Plans for the growth of solar power in states like Texas are stunning. Clearly, the economics of grid-scale solar power are rapidly improving, so much so that EIA projects that by 2028, solar power will become the second largest source of US electricity generation after natural gas. Indeed, EIA projects that renewable energy will surpass coal and nuclear generation by 2030:

But here’s the renewable rub. Solar and wind power now make up a little more than 5% of total US generation. These sources would have to double – and then double again – in the next nine years to meet the 2025 goal. While there is provocative work that posits that the US can get 80–85% of existing energy replaced by 2030 and 100% by 2050, that analysis is certainly open to questions, my own included.

Clearly, continued wind and solar cost declines, coupled with finding the right policies to facilitate advanced energy and energy efficiency, are key. And there’s a world of untapped potential in energy efficiency. But it’s pretty clear that nuclear power and CCS must be in the mix if the US is to meet the Summit’s goal – and go beyond it, as we must.

Renewables, as well as CCS and nuclear power, would obviously benefit from a price on carbon – something that’s widely supported – by economists anyway. But until that watershed moment arrives, and CCS is applied to both remaining coal and all natural gas-fired power plants, other approaches are needed.

The US experience with CCS has not been encouraging, despite developer’s statements to the contrary. The economics have so far been unforgiving. Alternative approaches to CCS, like the network concept that Pennsylvania briefly pioneered (and I led) during the Rendell Administration, are worth reviving. In fact, such networks have been proposed in the UK. So, too, is the concept of carbon utilization, typically starting with enhanced oil recovery (see, for example, NET Power) – and that I would drive to CO2 fracking.

Getting clean power to scale is likely best done by hedging our renewable energy bet with investments and policies to drive other alternative technologies.

John Quigley

Senior FellowJohn Quigley is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center and previously served on the Center’s Advisory Board. He served as Secretary of the PA Department of Environmental Protection and of the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.