Will Latest Solar Trade Dispute Impact U.S. Solar Growth?

Canary Media senior editor Eric Wesoff explains the latest in a history of solar PV trade disputes involving the U.S. and China, and what it could mean for the growth of solar power and domestic solar manufacturing.

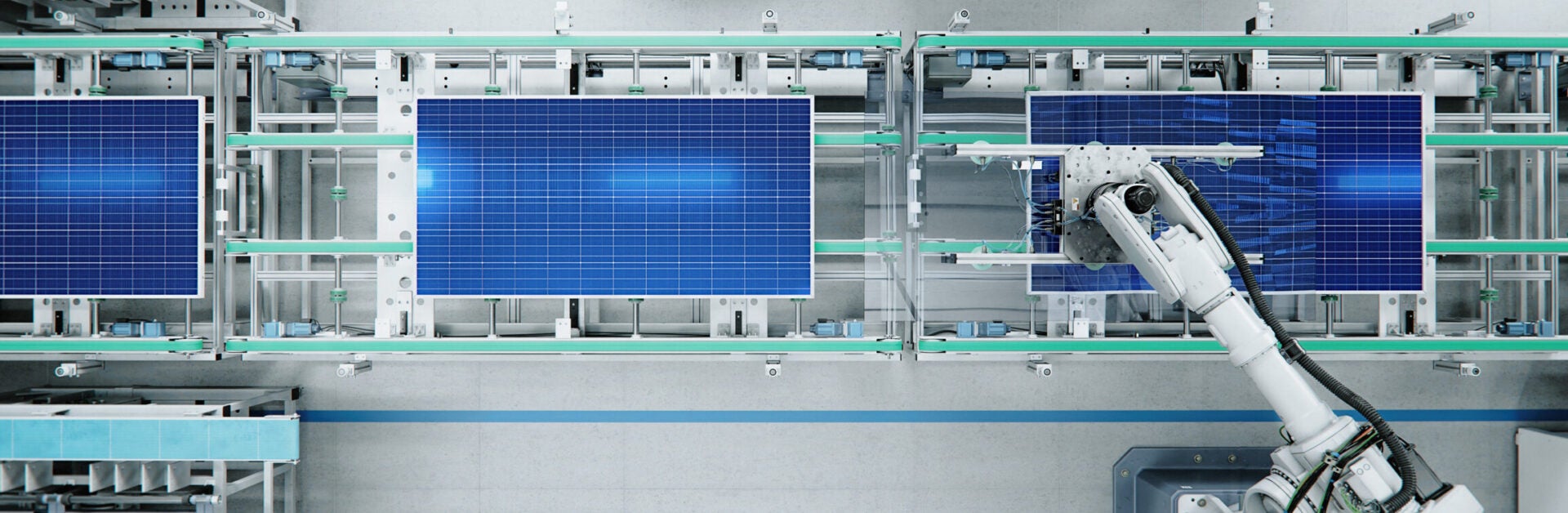

In April, a coalition of U.S. photovoltaics manufacturers petitioned the Department of Commerce to impose anti-dumping tariffs on solar panels from four Southeast Asian countries. The move is the latest in a long history of solar trade disputes involving China and, more recently, Chinese PV manufacturers operating throughout Asia.

Canary Media senior editor Eric Wesoff explains the foundations of the latest complaint, and how this case is substantively different from earlier trade disputes including the Auxin Solar case of 2022. He explores the competing priorities of the domestic solar manufacturing industry and solar project developers on the issue of tariffs, and how tensions within the industry create a Catch-22 for the Biden administration as it seeks to grow the solar industry at large with IRA incentives.

Andy Stone: Welcome to the Energy Policy Now podcast from the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. I’m Andy Stone.

Just two decades ago, solar power was a mere rounding error in the US electricity mix, an expensive form of power generation whose relevance seemingly remained far in the future. Today the industry is doing very well. Solar power accounts for over half of new generating capacity added to the US grid, and in states like California and Nevada, for a quarter of electricity produced. Yet the solar industry in the US is not a monolith, and policies that are welcomed by one portion of the industry may not be viewed so positively elsewhere.

We were reminded of this fact in April, when a coalition of US solar panel manufacturers called on the Department of Commerce to investigate illegal trade practices involving China and four Southeast Asian countries that supply the bulk of solar panels in the US. The challenge has been strongly opposed by solar project developers and clean energy associations. If the case sounds familiar, it is, to a point. China has long been at the center of solar trade disputes, yet the latest challenge comes as the US solar manufacturing sector is gaining size and strength, backed by financial incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Here to discuss the latest solar trade dispute is today’s guest, Eric Wesoff. Eric is Senior Editor at Canary Media, a media company focused on the energy transition. He’ll explain the current solar trade challenge and what it might mean for solar sector growth. Eric, welcome to the podcast.

Eric Wesoff: Thank you, Andy. It’s good to be here.

Stone: So Eric, you have a long history covering the clean energy industry. Could you give us a quick rundown on where you’ve been and how you ended up at Canary Media, where you are also the founder?

Wesoff: I’m currently the Executive Director, Founder, and occasional writer and reporter at Canary Media. Canary Media is a nonprofit media platform that covers the energy transition and solutions to the climate crisis and is one of the leading voices in climate news. But I’ve been covering renewables and solar in particular for going on twenty years, and I’ve watched it, as you said in your introduction, go from a rounding error to the driver of renewable growth in the United States and the world. Solar is the success story when it comes to clean technology and renewables. With that success, comes a little bit of tension when it comes to industrial policy, when it comes to US-Chinese relations, and when it comes to manufacturers versus developers in the United States.

Stone: I also want to point out a couple of interesting things about your background before we go forward. Many people may be familiar with Greentech Media, which is no longer around. We miss it very much, but you were Editor-in-Chief there, as well, and you’re also the US Editor for PV Magazine. Is that right?

Wesoff: Yes, and so I have a long, successful career covering renewable energy, and I’ve covered it from essentially zero to becoming a material force in our energy mix.

Stone: Let me ask you about that. To what extent is the fact that solar now accounts for

over half of new generating capacity something you’d expected when you were covering the industry, say twenty years ago? Is that a big surprise to you?

Wesoff: It has happened over the course of ten years, and since I’ve been swimming in this water, it’s hard to notice the news, but I’m jaded. In fact, it is revolutionary. It is inspiring, and it is disruptive, the fact that solar has gone from zero to the numbers you mentioned about the US, but also 10% of world electricity generation is solar now. The thing we haven’t even talked about is the pricing has just gone from 10 dollars per watt for a solar panel to 10 cents per watt for a solar panel these days. It’s an amazing example of industrial scaling. It’s also an amazing example of China taking advantage of industrial policy, and the US failing to take advantage of industrial policy. It’s a stunning example of the United States losing the advantage in a manufacturing industry and surrendering it to China.

Stone: I think that’s a really interesting point. Obviously solar prices come down, and that has enabled the growth that we’ve seen, that you just talked about in this country and globally, of PV. As you mentioned, China is very much a central player in this industry. Chinese companies are the dominant manufacturers of solar PV. I wonder if you could quantify how dominant China really is in this industry, and what has that dominance meant for the development of the US solar industry in its various facets?

Wesoff: I’ll point out first that the United States actually was once the manufacturing leader of solar, back in the ’90s. That manufacturing crown eventually went to Japan, later to Germany, but when the market was actually starting to heat up and grow, China got serious and established an industrial policy, invested hundreds of billions of dollars into its domestic manufacturing and its domestic deployment of solar, and has taken a lead in the world that is — I won’t say “insurmountable” — but it is of a scale several orders of magnitude larger than the United States’ manufacturing base. Today we are at 10 to 20 gigawatts of manufacturing capacity of solar modules in the United States. China is at 400 to 500 gigawatts of solar manufacturing.

Stone: Wow, like 20+ times the size of the US industry.

Wesoff: Yes, and growing and investing. So that’s the tension, one of the tensions of this conversation — we’re talking about tariffs. China is able to both manufacture at a larger scale in a manufacturing complex that’s vertically integrated at a scale beyond what we’re currently manufacturing, despite the great efforts in investments of the IRA, the Inflation Reduction Act. It is being accused by American manufacturers of selling below costs, of dumping. These incredibly cheap solar modules that are flooding European and American markets are making it impossible for American solar manufacturers — the few gigawatts of capacity that they have — it’s making it impossible for them to compete.

Stone: We’ve got this generally positive environment of growth of solar in the United States, but the PV industry itself is dominated by the Chinese. So into this situation comes the latest threat of a trade action. In April, the largest US solar manufacturers — those include a company called Qcells, as well as First Solar — were part of a larger group that has petitioned the Commerce Department to levy tariffs on PV imports from a number of Southeast Asian countries. What specifically here is the issue today, and what is the group asking Commerce to do, specifically?

Wesoff: Just to put it in a little bit of context, the United States has been petitioning China for fair trade tariffs since the Obama administration. It is a consistent piece of policy across administrations since then. The Obama administration, the Trump administration, and the Biden administration all have enacted tariffs against Chinese solar panels in various different formats.

What’s happening today is these large manufacturers you mentioned, the large American-based manufacturers like First Solar and Qcells are not saying that Chinese panels are the problem. They’re saying that China has essentially moved its manufacturing to force out these Southeast Asian countries and is dumping its product from those locations. It originally started out as what is called “circumvention.” In other words, it was a dodge. China was trying to do some finishing touches of solar equipment in these four Southeast Asian countries, with the majority of the important manufacturing being done in China proper, such as the polysilicon manufacturing and doing some of the assembly in these other countries. But they had their own integrated manufacturing going on now in these four countries, and so it’s no longer circumvention. It’s no longer trying to dodge. It’s simply anti-dumping and what is known as “countervailing duties.” Anti-dumping is accusing China of selling it below cost to garner market share or to crush the competition, and countervailing duties are sort of punitive damages.

Stone: So Eric, let me ask you a clarifying question here for just a moment. So we had tariffs imposed on Chinese imports two years ago, as a result of the Auxin Solar trade episode. We now see this happening two years later. You’re talking about anti-circumvention tariffs, which go back two years. Now we’re talking about anti-dumping tariffs. Can you give me a little bit more insight into what exactly was happening two years ago, and how is that different from what’s happening today?

Wesoff: The Auxin Solar case claimed that China was circumventing, or in plain English, dodging the tariff rules by doing most of its work in China, and doing some of the finishing work in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. That has changed. They actually have set up their own fully-integrated manufacturing supply chains in these four nations and no longer have to do the finishing work. They’re doing the actual work of manufacturing, but they are still dumping the modules, according to the claimant.

So that’s why the Auxin case from two years ago about circumvention is not enough, in the eyes of these claimants. They’re saying it’s no longer about circumvention. It is about dumping product at 10 cents or 15 cents per watt, when American manufacturers are in the 25 cents per watt or 30 cents per watt range.

Stone: Got it. And these companies that are in the four countries that we are talking about, those are still funded by the Chinese government. Is that part of the complaint, as well?

Wesoff: Yes, absolutely.

Stone: So it’s interesting. We’ve got this issue where there’s a threat here to the solar manufacturers in the United States from these cheap imports. I think I read in one of your articles on the topic that there are something like 30 gigawatts of imported PV modules, panels, from these countries that are basically waiting around in warehouses in the United States. That’s the extent of dumping that has gone on. Yet the developers love this, right?

Wesoff: The developers love it. Who wouldn’t love having high quality — hopefully high quality — cheap product to develop their projects with? So that’s the other tension that’s going on here, the American solar scene is not monolithic. There are manufacturers who want to compete against China, but there are also developers who want to install gigawatts of solar in every state of the nation, practically, and they want cheap, good components. And so the industry has this conflict within it of developers who want to deploy solar modules, and a burgeoning renaissance of American solar manufacturing.

Stone: I want to jump back just one more time, excuse me, to this trade dispute. Two years ago, we had Auxin, a very small company. This time, as we’ve already mentioned, we’ve got Qcells and First Solar leading the charge, or at least equal players in this charge, wanting to see this new round of tariffs. Why were the big guys not involved two years ago, but they are now?

Wesoff: Yes, Andy, that is a great question. The history of these tariff claims have been made by marginal or very marginal solar companies, so it is a big difference that First Solar and Qcells, the two largest domestic manufacturers of solar panels, have signed onto it. They talked to their lawyers. They talked to their PR people and decided that it was no longer a bad thing to be on this side of this.

So we talk about the tension between manufacturers and developers, but there is also a tension between incumbent manufacturers like First Solar and Qcells, and perhaps some new entrants. So you can see that as one of the areas of friction. First Solar and Qcells want to maintain their leadership in this. And so it’s a good question, and I’m not so sure of what the exact answer is, what prompted them to get on this time.

The other tension is US and China relations. I don’t think any American politicians went broke taking an anti-China stance. The Biden administration has to both coddle its domestic manufacturing base, but it also has to take care of the tens of gigawatts being deployed by developers. Then it has to sabre-rattle against China’s dominance. So there are a lot of trade plates being spun at the same time.

Stone: This is a familiar position for the current or any of the last three or four administrations to have found themselves in, right? Very clearly, under the IRA, there are incentives for solar manufacturing development in this country. The Biden administration wants to see that domestic solar manufacturing capability build up, become strong, to counter the Chinese dominance. Yet at the same time, it wants to serve the solar installers and make sure they have access to low-cost panels, to be attractive to their customers so that they can build a lot of solar installations. So they’ve got obviously this on-going Catch-22. Has the administration clearly taken any side early on in this case?

Wesoff: The administration two years ago, in pausing the Auxin tariffs in response to the existential howls of the deployment industry was a clear response, and they realized that cutting off the supply of cheap solar panels would cut off the development of new solar.

You’ve mentioned the IRA, and now is the time to talk about that policy. It’s hard to identify another policy in the United States other than the New Deal or the Great Society, in terms of the amount of money that’s being dedicated to the energy transition. The Biden administration wants to generate its own domestic supply chain. It wants to create jobs, and it wants to replace jobs from retired coal plants. It’s doing a remarkable job at this.

Tens of gigawatts of factories are now being built across the United States in what’s now called the “Battery Belt” in the Southeast. The carrots, the incentives in the IRA for manufacturing, the advanced manufacturing policy in the IRA and the variety of tax credits is an accelerator. It’s a spark plug for manufacturing built with steel in the ground. It’s happening now, but it can’t happen overnight. Amazing progress has been made in the two years.

So the carrot works. The stick of the tariff — I’ve covered this for 15 to 20 years. It’s hard for me to identify at any point when the threat of tariffs jumpstarted a manufacturing industry. So there’s another tension that we’ve come across in this conversation. It’s not questioning tariffs’ effectiveness, which I’m glad to do, but is the carrot or the stick the right type of industrial policy for the United States?

Stone: As you just pointed out, the solar manufacturing industry has grown significantly in the last two years, since the IRA came out. Prior to that, there were tariffs in place, but we did not see that same growth in solar manufacturing that is instructive. Interpret it as you will, I would imagine.

It’s interesting, as well, the industry organizations, the SEIA, the Solar Energy Industries Association and ACORE have both also come out against the possibility of tariffs resulting from this latest trade case. Why are they against it?

Wesoff: Well, they have their own set of tensions, and it would be difficult to be the CEO of SEIA, because your paying members are made up of both the solar manufacturers, like Qcells and First Solar, as well as the developers, and they have absolutely opposing agendas. So SEIA has to walk a very fine line and not anger too much either of those factions, or they’ve agreed to do that in a controlled manner. So yes, there is that same conflict between manufacturers and developers that impacts the way the trade organizations have to position themselves.

Stone: They’re also playing this as, “Well, we want stability for the industry. We want predictability and tariffs and these types of things. This is constantly throwing us for curves and loops.”

Wesoff: Yes, the industry talks of itself as being on the “solar coaster.” There’s always a government policy that’s either accelerating or decelerating the industry or again — leaving it with uncertainty.

Stone: So what are the next steps? When will Commerce decide if it wants to pursue this case by the time this podcast comes out? We’re recording on Thursday, the 9th of May. This decision may already have been made, but what is the timeframe looking like?

Wesoff: By the time this podcast is published, the Commerce Department should have decided to launch a probe, based on this new petition, and they probably will. That’s my handicapping of the situation. But from there, it will take up to a year to issue a final determination, although preliminary duties will be imposed in as little as four to six months. So that’s the timing. I would say it’s likely, and that it’s imminent that these will happen. And these are very significant amounts of duties, ranging from 7% of the price of the module to 270% of the price of the module, I think, for modules coming out of Vietnam — which brings forth the question: Do tariffs actually work? Different think tanks will come to different answers on that. But from my anecdotal experience with covering solar, I have not seen tariffs actually have their intended effect.

Stone: I think the flip-side question of this is, then so what would the impact be on installations?

Wesoff: The mere threat of tariffs from Auxin two years ago caused hysteria in the solar industry, and it has the potential to do that again.

Stone: Eric, I want to ask you kind of a final question here. China has obviously been extremely effective through its industrial policy of developing its solar industry, its electric battery industry. A lot of these new technology areas of China have been very effective. Do you see the United States with, for example, the help of IRA incentives providing the level of support needed to really compete with China? Can we compete with a country that is, at this point, so far ahead in terms of scaling and the policies it uses to develop its solar industry?

Wesoff: I think it’s unlikely that we’re going to be able to do that in the next decade. I do think that we will be able to — if we wish, we will be self-sufficient in our solar manufacturing. So we’re never going to be building hundreds of gigawatts of solar modules for export, but it’s easily visible that we can get to the 20 or 30 gigawatts of domestic solar capacity to satisfy our own needs and not to have to be dependent on China for what is arguably in the interest of our energy security in order to be self-sufficient on these components.

The jingoistic line is that we don’t want to go from dependence on Middle East oil to Chinese solar components or batteries. And so developing a domestic supply chain that can satisfy our own needs makes industrial policy sense.

Stone: Eric, thanks very much for talking.

Wesoff: Andy, thanks for having me.

Stone: Today’s guest has been Eric Wesoff, Senior Editor at Canary Media.

Eric Wesoff

Senior Editor, Canary MediaEric Wesoff is senior editor at Canary Media, and former editor in chief at Greentech Media. Previously he served as senior editor for solar publication pv magazine.

Andy Stone

Energy Policy Now Host and ProducerAndy Stone is producer and host of Energy Policy Now, the Kleinman Center’s podcast series. He previously worked in business planning with PJM Interconnection and was a senior energy reporter at Forbes Magazine.