Tritium: A Few Kilograms Can Make or Break Nuclear Fusion

As the nuclear fusion industry ramps up its technological, financial, and public momentum, private companies aren’t far from igniting the first constellation of reactors. The deciding factor no longer rests in the physical possibility of fusion, but in the prospect of fueling it. Companies must ensure stable, secure, and predictable fuel streams long before commercialization if they hope to make fusion a reality—else they run the risk of having billion-dollar facilities that can’t turn on.

If you’ve read anything on nuclear fusion (the process that powers the sun and stars), chances are you’ve stumbled across the line “inexhaustible fuel.” In a world where estimates say that known fossil fuel deposits won’t take us far beyond mid-century, fusion’s fuel promise couldn’t come sooner. With two hydrogen isotopes, deuterium and tritium, you can produce 20– 100 million times more energy than an equivalent quantity of fossil fuels. While the allure of harnessing the power of a star is understandable, the fuel poses a distinct obstacle for private fusion companies: accessibility.

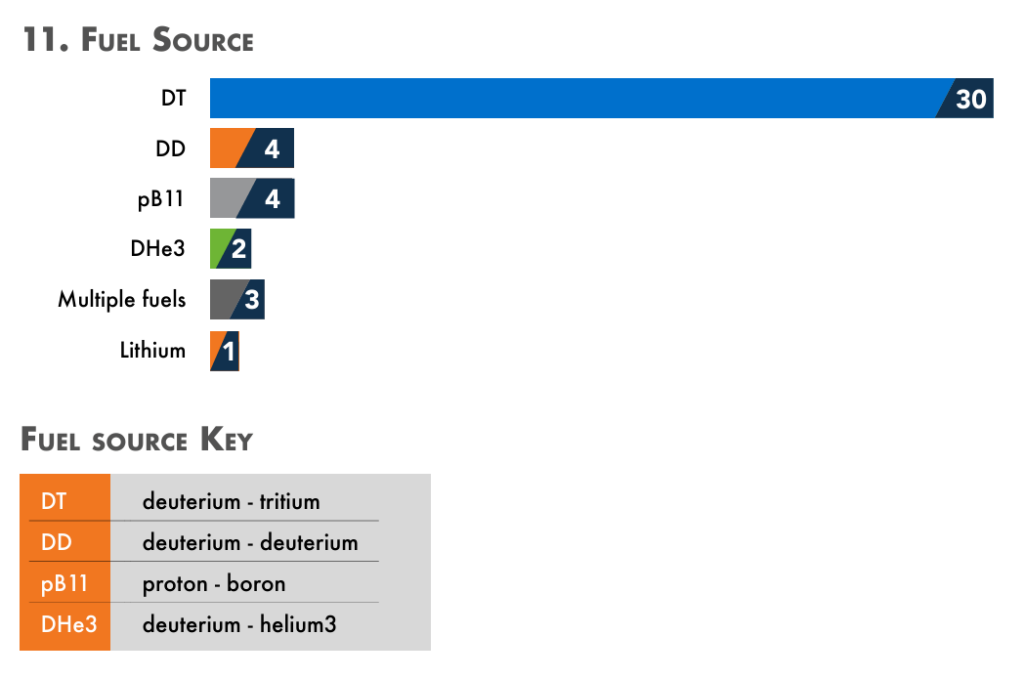

The good news: about every 1/6500 atoms in the ocean contains deuterium—that’s more than enough for large scale facilities. The bad news: tritium only occurs naturally when cosmic rays interact with nitrogen in the upper atmosphere. In nature, there are a meager 7.5 kg estimated to exist at any given time, but a 1GW fusion reactor alone could require nearly 55 kg of tritium to operate for a year. This poses a puzzling dilemma for the 70% of fusion companies surveyed by the Fusion Industry Association (FIA) that plan to operate on a deuterium-tritium (D-T) fuel composition. Fortunately for the fusion industry, nature isn’t tritium’s sole proprietor.

As of 2024, global stores of civilian-use tritium (anything non-military) are estimated to be approximately 25 kg, most of which is owned by Canada and produced from byproducts of Canadian Deuterium-Uranium (CANDU) fission reactors. These aging plants, first built in the 1970s, produce traces of tritium in the reactor core when deuterium atoms from the fuel absorb stray neutrons. Canada’s reactors generate a total of 2 kg of tritium/year, with any given CANDU reactor generating 130 g annually. Sadly, private fusion companies looking for a piece of the Canadian pie are out of luck because most of this volume is earmarked for research at the record-breaking International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER).

Alongside Canada, the United States produces roughly 2 kg of tritium/year at the Watts Bar reactors operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). This volume, however, is exclusively for defense applications in nuclear weapons. Tritium itself is a short-lived, radioactive isotope with a half-life of about 12 years. As a result, any stored quantity shrinks by 5%/year, making regular replenishment within these weapons a necessity. All current and future U.S. nuclear weapons require tritium for the intended damage upon detonation, so the limited quantities are heavily regulated and restricted.

The most widely recognized, and most promising, solution for private companies to get their hands on tritium is integrated and/or dedicated tritium breeding within fusion reactors themselves. It works by D-T fusion producing a free neutron and a helium atom. The neutron eventually strikes the interior of the reactor—a key for later power generation. However, if you line the reactor core with a blanket of lithium-6, it absorbs and reacts with neutrons to produce significant quantities of extractable tritium that can be redeployed to power the reactor. Studies suggest that the theoretical tritium production margins exist to satisfy a reactor’s fuel demands. As such, once you start-up a fusion reactor, it can run a near closed-loop fuel cycle. The catch is that this technology isn’t completely developed, and it hasn’t been demonstrated at scale—not to mention you need an operational fusion reactor for the breeding.

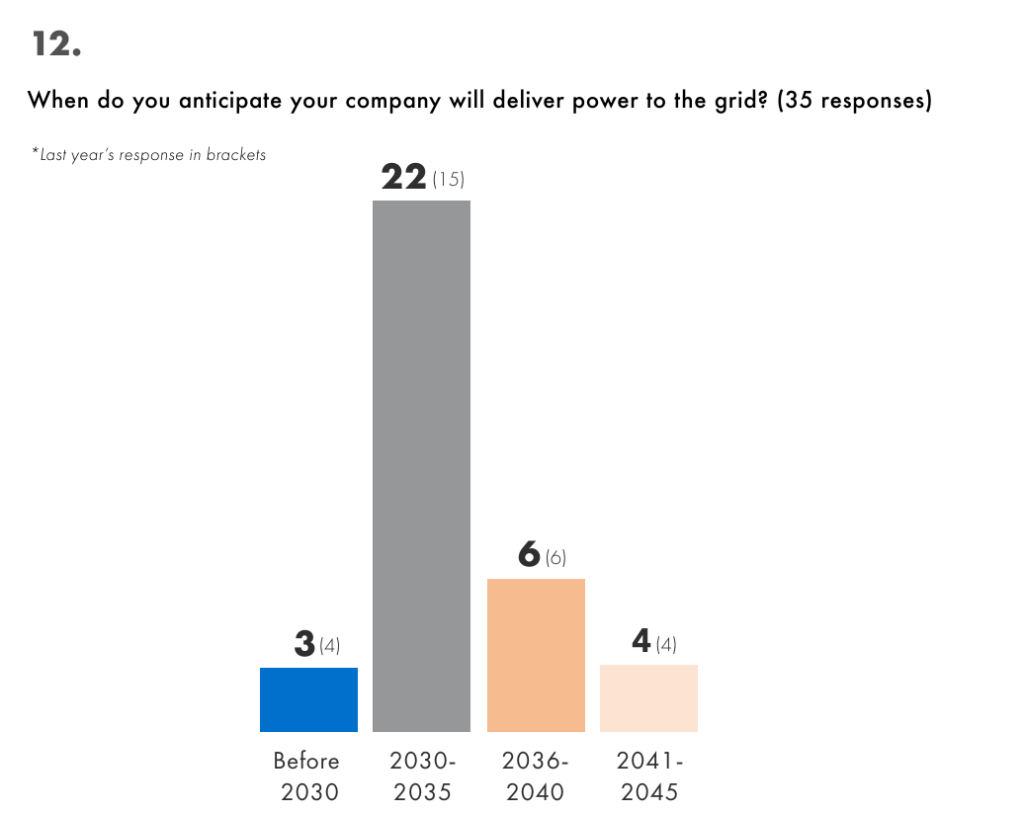

For private companies looking to commercialize by the early 2030s, tritium procurement is perhaps as important a hurdle to overcome as engineering to achieve ignition. With limited civilian-use tritium streams, highly regulated defense sources, exciting but youthful tritium breeding technology, and quickly approaching deadlines, near-term fusion operations will have the technology to make stars. The question is: will the reactors be able to keep them alive?

Tobey Theiding

Student Advisory Council MemberTobey Theiding is an undergraduate in the College of Arts & Sciences studying physics. Theiding is a Student Advisory Council Member and was 2025 Undergraduate Fellow.