Pennsylvania Highlights the Local Debate on Nuclear Waste Storage

Communities across the country might be surprised over how little say they have about the nuclear waste being indefinitely stockpiled in their neighborhoods.

The United States government planned to develop a centralized facility to store in perpetuity (think hundreds of thousands of years) the high-level radioactive waste that is left over from nuclear power production. But that hasn’t materialized, resulting in nuclear power plants across the country storing the waste on-site.

Earlier this week, the Salem Township (PA) zoning officer denied a permit request submitted by Talen Generation LLC – owner of the Susquehanna nuclear plant – to build a 22,000 square foot addition onto the plant’s existing spent fuel storage facility. In her denial, the zoning officer claimed that hazardous waste storage was not permitted in that zoning district.

On Tuesday, Talen won its appeal of the initial permit denial. This reversal was not because the zoning board thought the project should move forward, rather the board was compelled to recognize it did not have jurisdiction in the matter because federal law (e.g. the Atomic Energy Act and actions of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission) over the matter preempts state and local law under the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Similar local zoning disputes about plant expansion of waste storage sites popped up, for example, at Massachusetts’ Pilgrim nuclear station. And the extension of Pennsylvania’s Limerick nuclear power plant’s operating license was approved, after much community controversy about long term on-site waste storage.

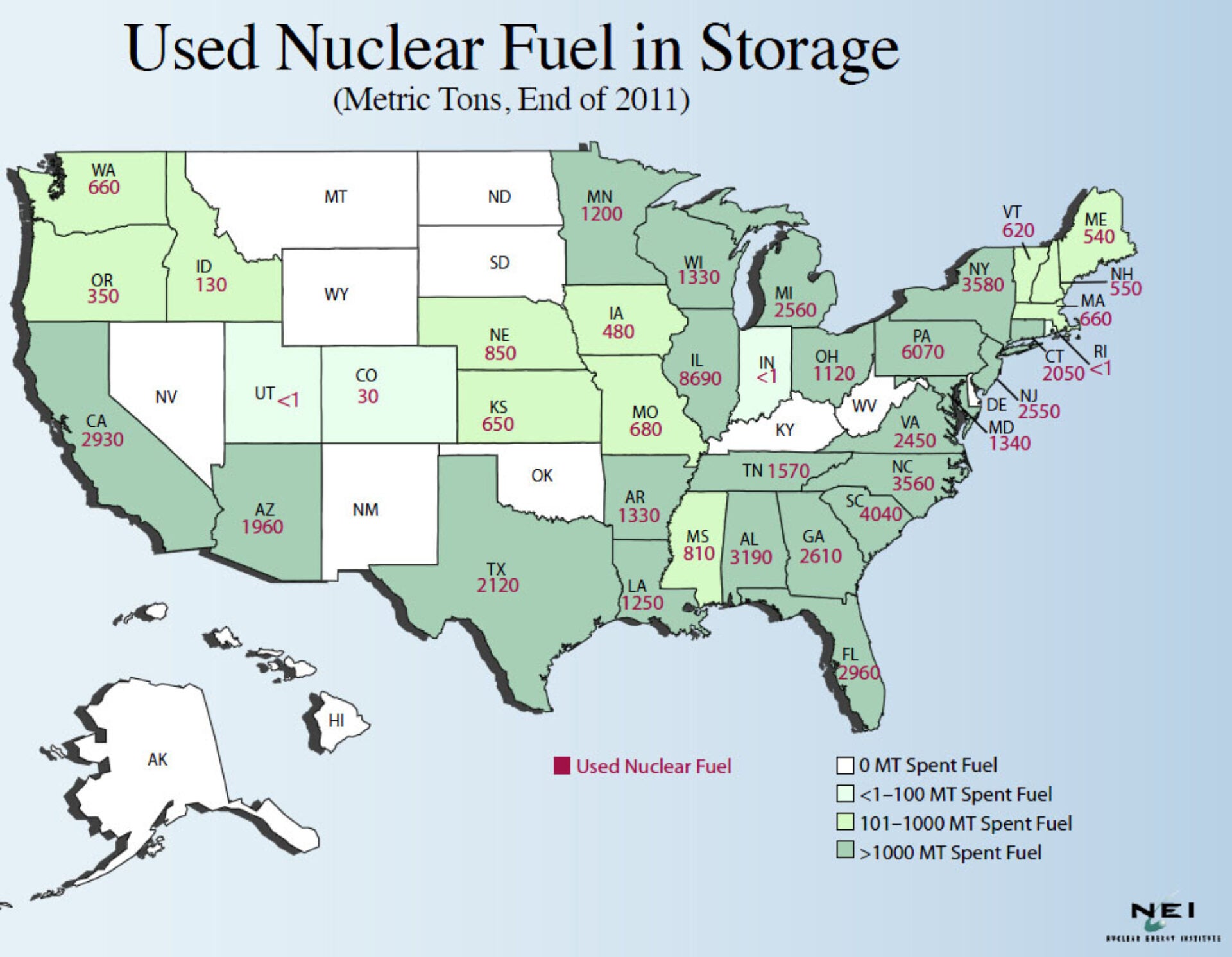

The U.S. Department of Energy was tasked with the siting and construction of a permanent nuclear waste storage facility and to date, Nevada’s Yucca Mountain has been the focal point of DOE’s politically stalled efforts. In the absence of permanent storage, there are approximately 76,000 tons of this waste being “temporarily” stored on-site at power plants and military facilities in almost every state across the country.

In 1984, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) believed a central storage facility would be available by 2007-2009, later pushing that date back to 2025, then abandoning a date-certain altogether. NRC originally believed this waste could be safely stored on-site for up to 30 years after plants ceased operations, but have been forced through state litigation to consider on-site storage for 60 year, 100 years and indefinitely. And NRC’s on-site waste assumptions are still being litigated by certain states.

The average age of the U.S. nuclear power fleet is 35 years. These plants receive operating licenses for 20-year periods, so many plants have or are in the process of seeking their third relicense and the assumption of indefinite on-site storage has to be considered in this process. Those that do not secure new operating licenses or shut down for economic reasons may be forced to decommission, complicating questions about long-term on-site storage.

Local government certainly don’t have the expertise to make decisions about nuclear waste disposal, which is one of the reasons Congress tasked the U.S. DOE with creating a central repository. However, when local governments agreed to host nuclear plants, roughly 35 years ago, none of these communities understood they were going to become the indefinite home of tons of highly radioactive waste.

And you can’t blame nuclear power plant owners either. These companies would much rather send their waste to the government-promised facility rather than having to spend money and manage the risks associated with indefinite on-site storage.

Nuclear energy provides 20 percent of America’s power and that power is carbon free. Current technology and climate change realities require nuclear power production to be viable.

No single state wants to be the home for all of America’s nuclear waste, but unless our leaders make a decision about a permanent disposal solution, almost every U.S. state will be forced to host this waste forever.

Christina Simeone

Kleinman Center Senior FellowChristina Simeone is a senior fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and a doctoral student in advanced energy systems at the Colorado School of Mines and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a joint program.