Learning From Uruguay’s Energy Transition

A small nation in South America may have cracked the code for decarbonizing electricity generation. Take a look at what they did and how the rest of the world can learn from it.

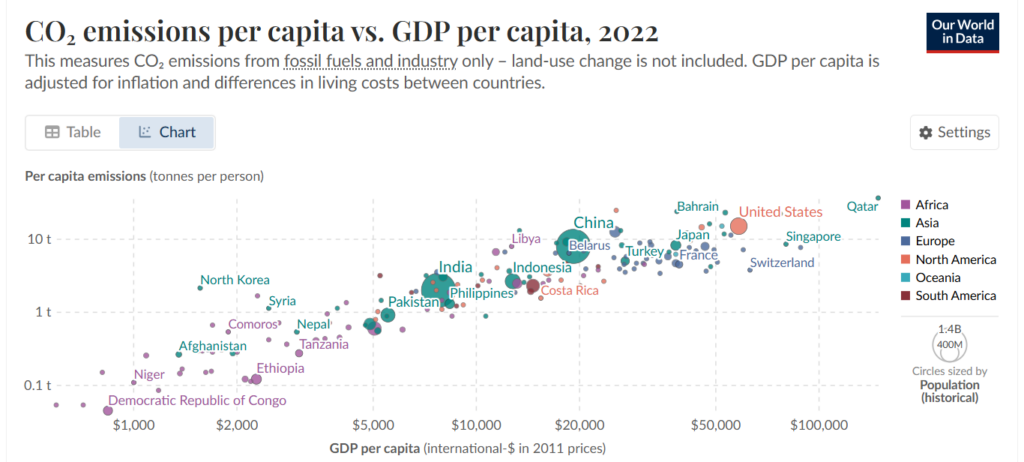

As countries become wealthier, their CO2 emissions typically increase following a power-law. This graph summarizes the trend.

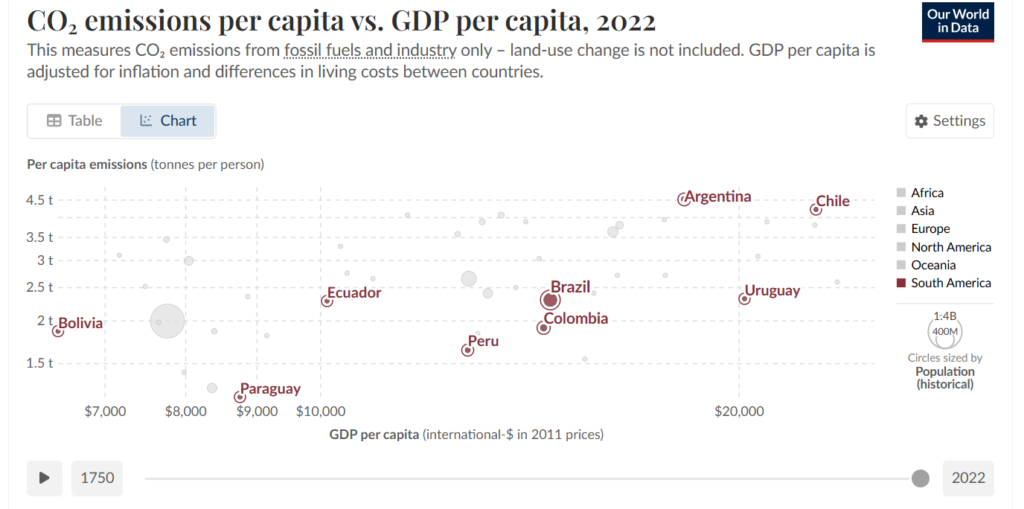

This relation is perhaps the biggest challenge to global decarbonization efforts. Wealthy countries are unwilling to decarbonize if it means too much economic sacrifice. Meanwhile, poorer countries increase their emissions as they develop. Yet, when we zoom in on South America, something interesting happens.

The trend looks similar except for one clear outlier, Uruguay. Uruguay’s per capita emissions are comparable to Ecuador’s despite having double the GDP per capita. Among high-income countries, it has the lowest per capita emissions in the world.

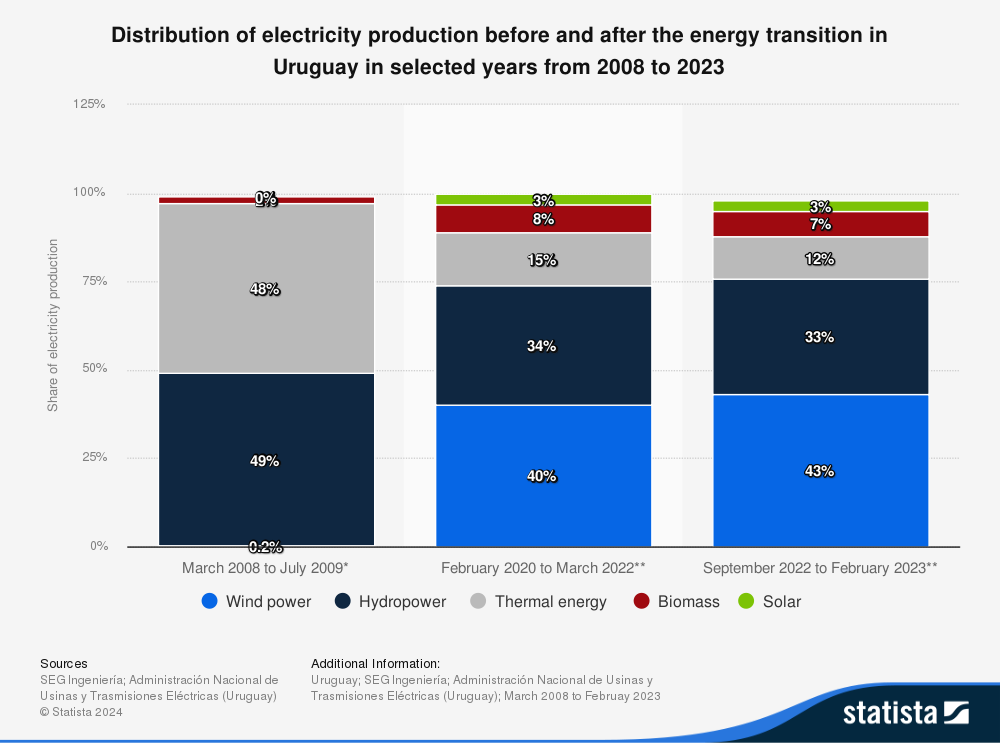

Uruguay’s energy transition started in earnest in 2008 when particle physicist and 2023 Carnot Prize recipient Ramón Méndez Galain developed a detailed and ambitious plan to shift to wind energy production. Méndez emphasized not just the environmental benefits but also the national security benefits of being less reliant on imports and fossil fuels. The Uruguayan government supported Méndez’s plan and appointed him to be the National Director of Energy.

Uruguay’s biggest challenge was finding the capital to build their clean energy capacity. For such a small country, relying on government spending would have been untenable. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank both declined to help, saying that the plan was impossible without heavy subsidies. Instead, Uruguay relied on a policy called feed-in tariffs. The state offered fixed long-term contracts to buy clean electricity at above-market rates (determined via auction). This gave firms certainty about their revenues, resulting in a huge influx of private capital. Between 2008 and 2015, private firms installed 581 megawatts of wind capacity within the country.

Based on the price of installing a megawatt, the policy probably attracted around $900 million of investment. As a fraction of GDP, this would be equivalent to $300 billion dollars of investment in the U.S. As a result, Uruguay is now very close to achieving net-zero electricity generation.

The apparent disadvantage of Uruguay’s feed-in tariffs is that the country is locked into paying higher prices for electricity than they might otherwise. But despite this, electricity prices for Uruguayans have fallen significantly.

There are a couple of factors at play here. The cost of wind energy fell markedly over the period in question. In addition, Uruguay began to export electricity during surges. Even so, Uruguay historically has some of the highest energy prices in the region.

The most important lesson that the world should take from Uruguay’s decarbonization is the utility of feed-in tariffs. Many developed countries already have a litany of green energy incentives on the books, yet our electricity generation has not changed significantly. Feed-in tariffs have a proven record of success where we have previously failed.

Feed-in tariffs will naturally be easier to implement in countries that have a single national electricity utility, like Uruguay. Examples include France and South Korea. But countries like the U.S., with our patchwork of local utilities, should still try. If the U.S. is to decarbonize, we need to reform our broken utility system regardless. Private American utilities could be induced to band together and implement feed-in tariffs through a combination of federal regulations and incentives. The federal government already regulates the sector heavily, so it is just a matter of providing the right incentives.

There is no shortage of clever ideas for combating climate change, but few have demonstrated as much success as Uruguay’s policies. If we are going to attempt anything at all, we should do what has been proven to work in the past–in other words, follow Uruguay’s lead.

Jack Leitzell

Undergraduate Seminar FellowJack Leitzell is a second-year student studying chemical and biomolecular engineering. Leitzell is also a 2025 Undergraduate Student Fellow.