Insights from the Political Economy of Climate Change and the Environment 2024 Mini-Conference

Explore blog posts from conference participants that delve into the political, economic, and social dimensions of climate and environmental policy.

Earlier this year, scholars gathered at the University of Pennsylvania for the second pre-American Political Science Association (APSA) mini-conference on the Political Economy of Climate Change and the Environment. This dynamic event featured paper presentations, lightning talks, and opportunities to connect on urgent issues in the environmental and political economy.

Here, we present a selection of blog posts from conference participants, offering reflections, research insights, and discussions that delve into the political, economic, and social dimensions of climate and environmental policy, showcasing the innovative work of both junior and established scholars. We hope you find these perspectives engaging and impactful.

The writing of the below blogs was overseen by members of the conference organizing committee.

Penn Organizing Committee: Parrish Bergquist, Alice Xu, Sarah Bush, Guy Grossman

From Ambivalence to Support: How Green Subsidies Can Change Climate Politics

Climate Policies: From Distributing Costs to Distributing Benefits?

Green energy subsidies can boost support for pro-environment parties by benefiting homeowners but risk excluding renters and low-income households from equitable gains.

The political acceptability of climate policies is crucial for achieving net zero objectives by 2050. Previous research consistently shows that carbon taxes, by imposing costs on vulnerable groups, are perceived as unfair and may push consumers of carbon-intensive energy to support climate-skeptic parties. The Gilet Jaunes protests in France exemplify this sentiment: a carbon tax on transport fuels sparked outrage among car-dependent workers in areas with limited public transport. While much attention has been given to how citizens respond to policies with concentrated costs, less is known about those with concentrated benefits.

This question is critical because shifting from distributing costs to distributing benefits might change the political logic of the energy transition, fostering economic optimism among recipients and potentially increasing support for accelerating the climate agenda. Can green policies create their own green politics, or, in other words, can governments use climate policies to increase the acceptability of the energy transition? Instead of focusing on who pays for climate action, what if we spotlight who benefits from it?

I study these questions in the context of the energy transition for households, which involves switching from fossil fuels to clean energy sources. Specifically, I study the case of feed-in-tariffs (FITs) for solar panel owners in Germany from 2001 to 2021. FITs are subsidies on the electricity produced and fed back into the grid. This policy implies receiving a monthly bank transfer over a 20-year period for whatever amount of electricity you produce.

This study views climate subsidies as conducive to environmentally sensitive wealth accumulation. Beneficiaries directly feel the financial benefits of climate policies while personally contributing to the energy transition. In the case of FITs, these benefits are concentrated among homeowners who use their home ownership claims to improve their properties with solar panels. This experience makes voters aware of the financial opportunities within the energy transition, often leading to greater support for the Greens, the party most aligned with generous climate policies.

Testing the Argument

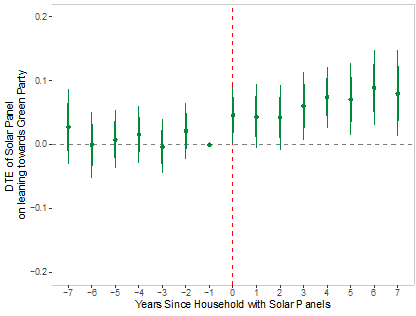

I test this argument using administrative data on solar panels, election results, and surveys of households with solar panels. Across multiple research designs, the results consistently show that homeowners are more likely to support the Green Party after buying solar panels, and this effect persists over time, as illustrated in Figure 1.

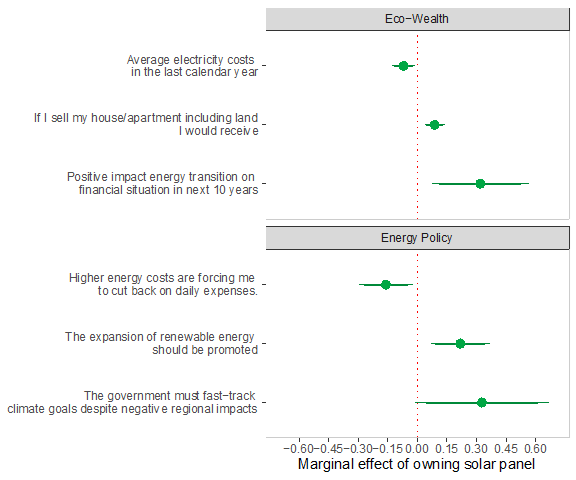

I then explore what explains these results and find that homeowners with solar panels report feeling wealthier and become supportive of ambitious renewable energy policies. Figure 2 shows that these homeowners observe lower electricity bills, believe their property values have increased, and are more optimistic about their long-term financial prospects in a green economy. They are less worried about rising energy costs and more in favor of fast-tracking climate goals, even if those policies might have regional economic impacts. These findings suggest that the economic benefits of solar panels lead homeowners to support the Greens, the party seen as most competent on climate policies.

Not All That Glitters is Gold

Returning to the initial question of whether policies can create their own politics, these findings suggest that green subsidies can create a virtuous cycle: they encourage clean energy adoption, which in turn builds a base of voters who support even stronger climate action. It is a powerful way to align personal financial interests with broader environmental goals.

However, the findings also suggest that most of these benefits flow to homeowners —people who already tend to be in a better financial position. In the context of housing crises across the Western world, policies that favor wealthy homeowners—who can leverage their homes to claim subsidies—may also shift costs onto renters. This logic extends to other housing assets beyond solar panels, such as heating systems or insulation reforms. Policymakers should, therefore, design policies that foster equitable outcomes, ensuring that especially renters and low-income households can also aspire to a better living standard in a clean energy world.

Martín Alberdi

PhD Canidate, European University InstituteMartín Alberdi is Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute. His dissertation explores the impact of climate policies on political behaviour broadly, with a focus on how these policies shape perceptions of wealth accumulation.

How Local Radio in Tanzania Can Boost Climate Change Awareness.

Climate news programs boost climate change awareness and conservation intentions in coastal Tanzania.

Imagine living in a rural community where your crops are failing, fishing yields are declining, and the weather seems more unpredictable than ever. You know something is wrong, but do you know that it’s part of a global phenomenon called climate change? For many rural Tanzanians, the answer is no. A recent study conducted by Salma Emmanuel, Donald P. Green, Dylan W. Groves, Beatrice Montano, and Bardia Rahmani set out to explore just how much people in rural Tanzania know about climate change and whether local media can help close that knowledge gap.

In our study, we wanted to see if local news programs could play a role in educating communities about climate change and motivating local environmental conservation. We worked with Pangani FM, a radio station in north-eastern Tanzania, to broadcast two news clips. One emphasised local responsibility, urging Tanzanians to take action to protect their environment. The other clip took a broader view, connecting the causes of climate change to the United States and China. With nearly 500 participants from 15 rural villages, we measured the impact of these broadcasts on listeners’ knowledge and actions.

Climate Change Awareness

So, what did we find? Before the study, 70% of respondents recognized that their environment was deteriorating, but just 53% were aware that human activities contribute to climate change. Even more surprising, only 16% knew that actions beyond Tanzania’s borders like industrial pollution from other countries were driving these changes. That’s a startling statistic, especially when you consider that Tanzania, like many other developing countries, is on the front lines of climate change impacts.

But here’s where it gets interesting. After listening to the climate change news clips, listeners’ awareness about climate change increased. People who heard the broadcasts were 27% more likely to say they’d heard of climate change, and 28% more likely to understand that human activity whether local or global was to blame. This is big news because it shows that a simple radio broadcast can make a real difference in how people perceive and understand climate change.

Local vs. Global Responsibility: What Motivates Action?

But raising awareness is just one part of the puzzle. The researchers also wanted to see if knowing more about climate change would make people more likely to act. This is where things got a little complicated.

Interestingly, listeners who heard the clip about local responsibility were more motivated to take action than those who heard about global causes. Those who were told that their own behaviours like cutting down trees or burning fuel contributed to climate change were more willing to report illegal activities like unpermitted fishing or logging in their communities. On the other hand, those who heard that the U.S. and China were largely responsible were less likely to take action locally.

This raises an important question: Does focusing on global responsibility make people feel powerless to make a difference? It seems that when people feel that the problem is caused by distant, powerful countries, they may think, “What can we really do about it here?” On the flip side, when people are told that their own actions matter, they may feel more empowered to protect their local environment.

What Can We Learn from This?

So, what can we take away from these findings? First, it’s clear that local media, especially radio, has a huge role to play in educating communities about climate change. In Tanzania, where radio is the primary source of information for many rural communities, it’s a powerful tool for raising awareness. But it’s not just about delivering information but also about how that information is framed.

If the goal is to encourage local action, focusing on how individuals and communities can make a difference might be the way to go. Yes, climate change is a global problem, but emphasizing that people’s everyday actions like reducing illegal logging or switching to cleaner energy sources can help protect the environment might motivate more immediate, tangible action.

Second, this study highlights the importance of tailoring climate communication to specific audiences. Rural communities in Tanzania are facing the direct impacts of climate change, but their knowledge of what’s causing these changes and how they can respond is still limited. By using local media to frame climate change in a way that resonates with these communities, it may be possible to turn that awareness into meaningful action.

Salma Emmanuel

PhD Candidate, Makerere University Business SchoolSalma Emmanuel is a PhD candidate in Energy Economics at Makerere University Business School. Her research focuses on the intersection of climate and media, energy and development. A former World Bank Fellow, Salma has worked and remains affiliated with the University of Dar es Salaam.

To Tackle Environmental Pollution, Indians want Rules and Regulations

A majority of Indians support policies that seek to clean up environmental pollution, even if it means raising taxes.

“Pollution is a planetary threat.” This is what Lancet researchers concluded in a 2022 report that found that one in six annual deaths worldwide were attributable to pollution—posing a serious health risk to citizens and contributing to increased climate change. This is especially the case in developing countries experiencing rapid economic growth. Despite deep costs to citizens’ quality of life, democratic countries have done little to address environmental harms. Why?

One explanation is that citizens and political leaders in developing countries are willing to overlook the proper treatment and disposal of waste in the quest for economic growth because it can be cheaper to use more polluting production processes, fuels, and technologies. Only after achieving higher income levels would people advocate for cleaner, yet perhaps more costly, economic practices. A second view argues that because pollution’s impacts on health and productivity are not as directly and immediately observable as other health issues like famines, it is difficult for pollution to elicit mass mobilization and electoral pressures.

In our project, “Determinants of Popular Support for Environmental Policy in India,” my co-authors and I investigate a new set of explanations that focus on the style of political competition in developing democracies. In countries where politicians provide goods and services in exchange for electoral support, voters might be less likely to support broad-based policies like rules and regulations that do not allow for targeted benefits towards electoral supporters. This is a problem because combating pollution requires strong regulations and enforcement to promote cleaner practices and proper disposal of waste. Identity politics and ethnic voting, compounded by the tax burdens of environmental action, might further complicate broad-based electoral mobilization on pollution abatement.

We field a first-of-its-kind nationwide survey on attitudes towards environmental policy in India, the world’s most populous country. Pollution is a dire problem in South Asia. Recent data, for example, found that 46 of the 100 most polluted cities in the world are in India, with a significant number also found in nearby countries like China, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Not a single district in India meets the World Health Organization’s guidelines for annual exposure to particulate matter, microscopic pollutants that are absorbed into the bloodstream and contribute to increased incidence of heart and respiratory disease. By some estimates, the lifespans of northern India’s 510 million residents are set to be cut short by about 8.5 years if current pollution levels persist. This is higher than the 2.5 years of life expectancy people are estimated to lose due to smoking in the same region.

In our survey, we experimentally vary the attributes of a hypothetical environmental policy being put forth by a politician running for office. While previous theories argue that the lack of action on environmental pollution in developing countries is partly due to a lack of demand amongst voters—either because they are assumed to prefer fewer environmental restrictions on economic activity or see pollution as less of an immediate issue—here we find that the average Indian does see pollution as a threat to their quality of life. Importantly, we find that a majority of voters in India prefer policies that use rules and regulations over schemes and subsidies to enforce the use of cleaner fuels and help reduce waste. Additionally, although citizens are markedly sensitive to the tax burden of pollution abatement policies, we find that a majority of voters support the hypothetical policy even if it means raising taxes. A series of additional analyses allows us to investigate how the structure of political competition in developing democracies shapes political demands for pollution control.

Environmental pollution is a major problem, one that even wealthy cities in the developed world can struggle to solve. However, inaction on environmental pollution in developing countries like India cannot be blamed on voter antipathy.

Aura Gonzalez

PhD Student, Cornell UniversityAura Gonzalez is a PhD student in the Department of Government at Cornell University. She is currently a visiting graduate student at the University of California San Diego and is a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow.

The Politics of Environmental Risk

Vulnerability, Legibility, and the Right to Housing in Informal Urban Settlements

This research examines how state policies of mass eviction and displacement in informal urban settlements are justified under the guise of environmental risk, using Rio de Janeiro as a case study to explore the contested political dynamics that influence which communities are targeted for removals and which receive infrastructural improvements to mitigate climate hazards.

On the margins of the world’s cities, the one billion people who reside in informal urban settlements (often referred to as slums) are among the most vulnerable populations to the accelerating effects of climate change, particularly the threat of natural hazards such as landslides and floods (UN Habitat 2022; Musungu et al. 2016; Williams et al. 2019). Municipal governments have historically intervened with a range of policy interventions in response to the risk of natural disaster, including removing and resettling residents in areas deemed to be of high environmental risk (Adger et al. 2018). These removals are justified by political officials as protecting residents’ safety, promoting sustainable urban development, and bolstering progress towards climate resilience measures. However, residents of informal settlements across many cities have increasingly resisted these displacement-based policies and made demands on the state for more effective environmental policy, citing inequalities in which communities become targeted for removal and which communities instead receive infrastructural improvement projects to reduce risk.

Why do residents of informal settlements faced with comparable levels of environmental risk receive different environmental policy outcomes? In my dissertation project, I develop and test a theory of political behavior surrounding communities located on land designated as “high risk,” focusing on state policies of mass eviction and displacement (known as “removals”) in response to the threat of landslides and floods. Beyond the geographic levels of risk to natural hazards, I will demonstrate how contested political dynamics between community-level residents’ associations and the state shape variation in environmental policies in informal settlements. These dynamics, in turn, shape the strategies employed by residents in making demands on the state to respond to and prevent these hazards. In my dissertation, I investigate how environmental policy outcomes are jointly shaped by citizens’ collective demands and the interests and discretion of municipal governments. Here, I focus on the politics of removals as an outcome resulting from politicized designations of environmental risk: which households become classified as “high risk,” how removals are justified by the state, and the patterns of claim-making and resistance by residents and community-level organizations around environmental risk.

To develop my theory of these highly localized political dynamics, I zoom into the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil as a case of a variegated and contested politics of removals surrounding environmental vulnerability. While this complex interplay between environmental risk and removals is salient across many cities, Rio de Janeiro serves as a particularly salient case of variation in both state behavior and civil society mobilization surrounding environmental vulnerability. In focusing on the broader politics of environmental risk rather than responses to punctuated natural disasters, I seek to provide a novel account of the more everyday, quotidian politics of environmental risk.

I argue that in framing what is inherently subjective in objective terms, logics of environmental risk serve as a primary justification through which municipal governments are able to increasingly invoke sweeping eviction-based policies and advance a broader political agenda of forced removals, thereby transforming an urban problem into an environmental one (Heck 2016). This strategic reframing and problematization of urban informality in the name of climate action allows the state greater discretion in targeting specific favelas for removal over others, as well as greater ease in carrying out removals as compared to other legal justifications. Using a multi-method approach including the analysis of removal records, interviews, participant observation, and a survey experiment of favela residents, this work will provide novel theoretical and methodological contributions to the literature on the political economy of the environment and urban politics in the Global South.

Emily Gregory

PhD Candidate, University of Virginia Department of PoliticsEmily Gregory is a PhD Candidate at the University of Virginia Department of Politics, where she studies urban politics in the cities of Latin America. Her broader research agenda centers around the brokerage of local housing, social, and environmental policies in informal urban settlements.

Bolivia’s Silent Crisis: Wildfires and Deforestation in the Amazon

Bolivia’s current environmental crisis is the result of recent policy shifts favoring agribusiness, coupled with the weak enforcement of environmental regulations—a problem deeply rooted in political patronage.

Fires are once again rampaging the Amazon rainforest. While stories of blazes across Brazil’s territory, the dried-up Amazon River, and worsened air pollution in São Paulo and Brasília have dominated headlines, the neighboring Bolivia is quietly grappling with its own environmental catastrophe.

According to the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS) by Copernicus and NASA, Bolivia has burned 12.5 million hectares by mid-September 2024—an alarming 11.55% of the country’s total land area. A state of emergency has been declared in the country, with flights canceled and schools closed as thick smoke blankets major cities.

These devastating fires brazing through Bolivia’s landscapes are part of a broader pattern of environmental degradation. Between 2001 and 2023, Bolivia ranked the tenth in the world for deforestation during that period. In just 2023, Bolivia lost 1.1% of its forested land, a rate double that of neighboring Brazil (0.54%). Besides a hotter and dryer climate, the forces driving fires and deforestation in Bolivia are primarily linked to the expansion of agriculture—particularly the cultivation of soy and cattle ranching. This rapid deforestation is endangering vital ecosystems, from the Amazon rainforest to the Chiquitania dry forests and the Chaco savanna. The destruction isn’t just a local issue—it has global consequences, accelerating climate change, reducing biodiversity, and threatening the health and livelihoods of local populations.

Bolivia’s forest law, passed in 1996, has relatively stringent regulations on forest conservation and control for agricultural fires. So, why wasn’t it effective in preventing the environmental destructions we see today? Part of the answer lies in the shifting regulatory environment. The left-wing political party which has been in power since 2006, the Movement for Socialism (MAS), initially promoted environmental protection, exemplified by the 2010 Law of Mother Nature. However, pressured by agribusiness interests and economic challenges, the government began prioritizing agricultural expansion through a series of laws that facilitated forest conversion. For example, law 741 of 2015 raised the limit on how much land smallholders could legally deforest from 5 to 20 hectares. In 2019, Supreme Decree 3973 permitted the use of fire for forest clearing in Santa Cruz and Beni, the two most important regions for agribusiness. These measures marked a departure from the government’s previous environmental rhetoric and reflected a new alignment with agribusiness interests.

Beyond legislative changes, enforcement of forest laws has been a significant challenge. The enforcement rate for illegal deforestation sanctions is extremely low, and while some of this can be attributed to bureaucratic inefficiency and a lack of capacity, politics also plays a crucial role. Similar to what others have found in Brazil and Colombia, deforestation in Bolivia is often used as a political tool, with illegal clearing tolerated to reward political supporters. As a result, the enforcement of environmental laws is weakened, and illegal deforestation often goes unpunished.

Despite Bolivia’s outsized role in the Amazon’s deforestation crisis, it remains largely overlooked in global conversations. More attention and research are urgently needed to understand the country’s unique political and environmental drivers of forest loss. Addressing Bolivia’s deforestation is critical not only for protecting local ecosystems but also for safeguarding global climate stability.

Yifan (Flora) He

PhD Candidate, UC Santa BarbaraYifan (Flora) He is an environmental politics scholar and a PhD candidate at UC Santa Barbara. She combines causal inference, geospatial and remote sensing data, and qualitative interviews to study land and natural resource governance in Latin America.

Breaking Barriers or Reinforcing Bias?

Climate Crises and the Gender Divide in Political Leadership

Natural disasters have the power to either reinforce or disrupt traditional gender roles, influencing women’s pathways to political leadership. Understanding how climate change shapes these dynamics is crucial for advancing gender equity in politics.

Natural disasters are a powerful force that often exposes the vulnerabilities within existing political, social, and economic systems. These events highlight the differential impacts on various demographics, particularly in terms of gender. While some argue that these crises may present opportunities for women to break through leadership barriers, others suggest that disasters may deepen pre-existing gender biases, leaving women further marginalized.

When disaster strikes, women and children are disproportionately affected. Statistics show that women are 14 times more likely to die in natural disasters compared to men, largely due to limitations in mobility, access to information, and decision-making power. Moreover, 4 out of 5 people displaced by the impacts of climate change are women and girls. Disasters also disrupt essential services like sexual and reproductive health care, compounding the adverse effects on women and girls.

These inequalities do not stop at survival and recovery but may extend into the political sphere. Despite global trends showing that women’s political representation is increasing, barriers remain, especially in particular crisis contexts. Female politicians may be subjected to harsher evaluations during and after natural disasters than their male counterparts. Voters may unconsciously (or intentionally) revert to traditional gender roles, perceiving men as more competent in crisis management, which could further hinder women’s chances of gaining or maintaining leadership positions.

My working paper is among the first to explore whether natural disasters influence gendered electoral accountability. By analyzing mayoral elections in the Philippines, I find compelling evidence that voters not only assess incumbents retrospectively but also evaluate female incumbents against disproportionately stricter standards in the wake of natural disasters. Specifically, municipalities experiencing higher levels of typhoon damage are significantly more likely to penalize female mayors, as demonstrated by notable reductions in their vote shares in subsequent elections. This pattern underscores the existence of deep-seated gender biases, which become particularly pronounced in crisis contexts. These findings provide crucial insights into how crisis conditions not only reinforce but may also intensify gender inequalities in political leadership.

Several factors may contribute to the perception of women as ineffective in crisis management. Natural disasters may amplify the persistence of the ‘old boys’ club’ in politics—a dynamic that disproportionately disadvantages female leaders by limiting their access to formal networks. These male-dominated networks can impede female politicians’ ability to secure and mobilize critical resources, such as disaster relief funding, essential for effective recovery and reconstruction efforts. As a result, despite no fault of their own, female politicians may struggle to access necessary resources, leading constituents to view them as passive, incompetent, or unfit to manage crises triggered by the sudden impacts of climate change.

Women have been at the forefront of climate action and climate justice movements, and need to be included in climate policy discussions. As research indicates, women play a pivotal role in tackling climate change. For instance, private sector companies with a larger share of women on boards are more likely to improve energy efficiency, reduce firms’ overall environmental impact, and invest in renewable energy. Likewise, nations with higher proportions of women in Parliament are more likely to ratify international environmental treaties and adopt stricter climate policies. These examples underscore that women prioritize long-term resilience and equity when they achieve leadership positions—key factors in effectively addressing climate challenges.

Gender bias in leadership during and after natural disasters remains an underexplored issue, particularly as climate change intensifies. The growing demand for leadership that addresses the unique vulnerabilities of women and other marginalized groups is clear. This intersection of disaster response and gender equality offers both a challenge and an opportunity for policymakers to integrate women’s perspectives into climate solutions. By better understanding how sudden climate crises affect women’s political trajectories—whether through ambitions, electoral success, or tenure—we can craft policies that not only mitigate disaster impacts but also promote gender equity in leadership. Ultimately, achieving gender balance in leadership will be one step towards ensuring that preventative, recovery, and reconstruction efforts are more equitable, resilient, and effective.

Holly Jansen

National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow, UC San DiegoHolly Jansen is a National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow and a Political Science Ph.D. student at the University of California, San Diego. Her research focuses on the gendered effects of climate and natural disasters.

The Politics of Transferable Skills and Energy Transition

As the transition to clean energy accelerates, many carbon-intensive workers and communities face significant economic challenges. My research explores how this shift influences political behavior in the U.S., revealing that Republican candidates gain ground in areas hit hardest by job losses in polluting industries. However, where workers find suitable alternative employment, the swing toward the GOP is much weaker. The study highlights the importance of targeted support for vulnerable regions to not only ensure a just transition but also to build broader political support for climate action. Without this, resistance to decarbonization may grow in struggling communities.

As the global community confronts the necessity of transitioning to clean energy sources, it is increasingly crucial to examine the political implications of this shift, particularly in regions where carbon-intensive industries form a core part of the economic structure. Significant components of climate policy initiatives, such as the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and the European Union’s Just Transition Mechanism, are aimed at supporting voters and regions for whom these polluting industries remain vital to their livelihoods. However, a growing body of economic literature highlights the challenges faced by workers in declining “brown” sectors as they attempt to transition to “green” and expanding industries. Contrary to dominant narratives, the shift to a low-carbon economy involves substantial economic disruptions and permanent income losses for many workers across various sectors. My research investigates the political consequences of these challenges in the United States, where fossil fuel production continues to drive economic well-being in many communities across the nation.

My paper first examines the ability of workers in carbon-intensive industries to transition to alternative, non-carbon-intensive sectors. It identifies 16 occupations most at risk of displacement due to decarbonization. I then assess the ease with which these workers can transition, based on their current skill sets and the availability of alternative job opportunities within local labor markets. For each election year from 2004 to 2020, I create a “Vulnerability Index” that captures the susceptibility of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) to the effects of energy transition.

My research produces three key findings. First, it shows that voters tend to reward Republican presidential candidates in response to job losses in carbon-intensive industries. Since 2004, Republicans have gained significant support in areas heavily reliant on these sectors. Second, I analyze how the “Vulnerability Index” influences electoral behavior. The results indicate that in MSAs where carbon workers can find alternative jobs that match their skills and income levels, the shift toward Republican candidates is significantly reduced. Conversely, Republicans gain substantial ground in areas where job loss in carbon-intensive sectors is severe and alternative employment opportunities are scarce.

The response of voters to carbon-intensive job losses appears closely tied to the availability of suitable job alternatives in their local labor markets. The loss of well-paying jobs in regions with few alternatives can severely impact a worker’s lifetime income and undermine a community’s economic base. Policymakers recognize the importance of supporting workers in sectors expected to decline due to energy transition, but U.S. federal support has historically been limited. While the Biden administration’s recent efforts to facilitate labor market transitions are generous, they have not been systematically targeted at the most vulnerable areas, potentially hindering the progress of energy transition. Addressing the welfare concerns of affected workers is critical not only from a perspective of distributive justice but also to build a broader political coalition in favor of decarbonization.

This paper contributes to policy and academic discussions on just transition and place-based industrial policies, both in the U.S. and other advanced economies. It demonstrates that not all carbon-intensive workers and communities require the same type of public support to transition successfully to greener sectors. To expand political support for climate action, greater attention must be given to regions where carbon-intensive jobs remain the primary source of well-paid employment. If too many of these regions are left behind in the energy transition, my research suggests that politicians who oppose rapid climate action are likely to further strengthen their appeal in economically declining energy-dependent communities.

Florent Pepin-Proulx

Doctoral Canidate, University of GenevaFlorent Pepin-Proulx is a doctoral candidate at the University of Geneva, soon to commence post-doctoral research at Indiana University. His research focuses primarily on the political economy of climate policy.

When Do Congressmembers Break the Party Line on Climate Policy?

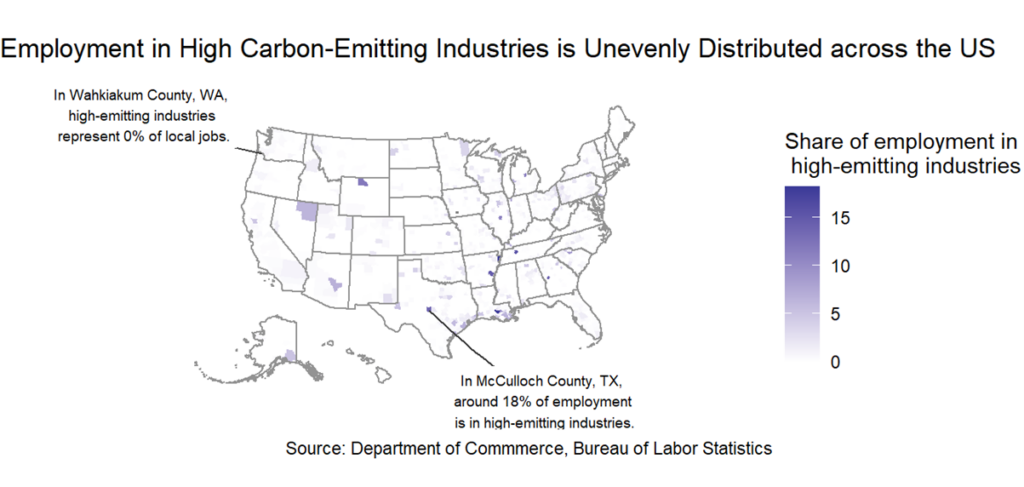

Congressmembers repeatedly defied their parties on climate policy between 2009 and 2022. The uneven distribution of employment in high-emitting industries across the United States can help explain those deviations.

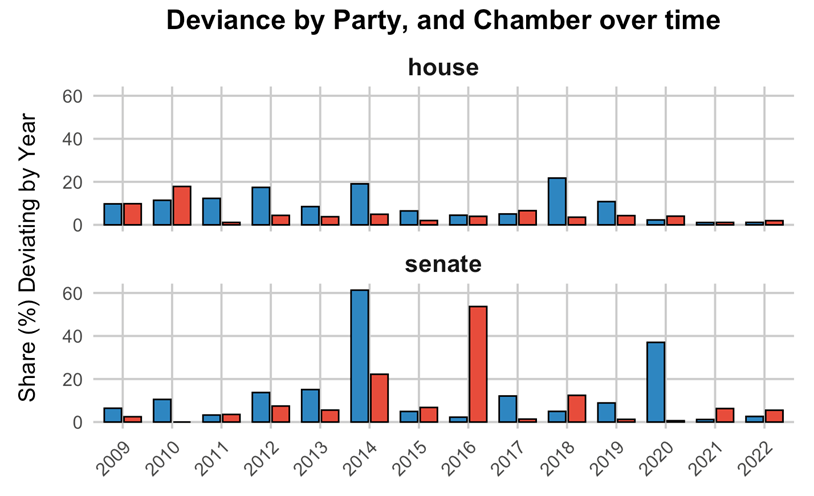

Despite being a highly polarized issue, 234 House members and 65 Senators voted at least twice against their party’s position on climate policy between 2009 and 2022. My research project sets out to explain these deviations. A better understanding of these deviations could help strengthen the political feasibility of climate policies.

My initial analysis finds that district-level employment’s exposure to climate policy helps explain deviation from party lines on climate roll call votes. I look at 35,000 positions taken by House members in roll call votes on climate policy, as well as 56,000 by Senators over 2009-2022, and assess whether the congressmember voted in a way that was aligned with the League of Conservation Voters.

My preliminary findings suggest that high shares of h-e employment make Democrats (Republicans) more (less) likely to deviate from their party on climate policy. The effects are larger in close votes. Tightness of the previous election also increases the effects, suggesting fear of sanction.

To model this exposure, I assess which industry subsectors have the highest levels of carbon intensity across their supply chain, ie. the highest amount of carbon released for every additional dollar of value add. In effect, these are the subsectors that would be most affected by a change in the social, or actual, cost of carbon. I then estimate district-level employment in these industries. These jobs are not evenly distributed in the United States.

My research also documents that the political influence of high-emitting employment is magnified by the first-past-the-post electoral system of the US Congress, and by the high multipliers associated with jobs in h-e industries. This can help explain the significant effect on congressional roll call votes, despite relatively low levels of exposure.

These findings are in line with qualitative evidence from congressional candidate campaign debates. Concerns about jobs (and ripple effects) are a repeated argument used to criticize climate action between 2009-2022, including in this debate for Indiana’s 9th District in 2010:

“I wish you would have sided with Indiana employees and and not voted for this job-killing legislation [Cap and Trade… it] will increase the cost of business here in places like Indiana. Jobs will migrate overseas to places like China [… while] we single-handedly kill over 40,000 Hoosier jobs and make the environment dirtier in the process.” — Todd Young (R)

The uneven distribution of exposure to climate policy across the United States, particularly in terms of employment, influenced votes on climate policy between 2009 and 2022 in Congress, and should not be ignored in the crafting of climate policy going forward.

Peter Wyckoff

PhD student, London School of EconomicsPeter Wyckoff is a PhD student at LSE, in the Department of Government and the Grantham Research Institute. His research focuses on the distributional impacts of climate policy, and on electoral institutions. He previously worked for the OECD and European Commission.

Why Do Firms Participate in Voluntary Carbon Markets?

A multi-level framework of global private governance

This study examines the variations in corporate engagement in Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs). We propose a multi-level framework of firms’ participation in VCMs, which integrates factors at the firm, country, and transnational levels. We demonstrate via various modeling strategies how these multi-level factors affect firm’s participation.

Non-state actors appear to be “global governors” in the global policy arena. While the “regime complex” theory traditionally emphasizes that non-hierarchical institutions can manage specific global issues, it largely neglects the role of non-state actors in global politics. Indeed, nonstate actors are actively involved in global climate governance, contributing to efforts to achieve sustainable outcomes. For the first time, the Paris Agreement has recognized the role of sub- and non-state actors in helping countries achieve the global temperature target below 1.5 °C and called on “non-party stakeholders” to amplify their climate commitments.

Among these non-state actors, corporations increasingly establish firm-level net-zero targets and actively participate in Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs). VCMs are a critical market-based policy tool to control greenhouse gas emissions, allowing entities based on voluntary purposes to purchase carbon credits to neutralize residual emissions that cannot be further reduced cost-effectively. The Glasgow Climate Pact, adopted at the 26th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, has recognized the role of VCMs in climate mitigation activities. However, corporate participation in VCMs varies significantly by region and country, with European Union and North American firms being the most active. How do we explain the variations in corporate engagement in VCMs? Why do firms from some countries choose to participate in VCMs, whereas others do not?

Existing research suggests that the firm’s determination to fulfill net-zero targets directly triggers corporate participation in VCMs. However, deciding to participate in VCMs depends on a firm’s assessment of potential costs and benefits. Motivations for firms to engage in VCMs can be attributed to factors originating from both macro and micro levels. Thus, this study proposes a multi-level framework to investigate corporate participation in VCMs, which integrates factors at the firm, country, and transnational levels. We demonstrate that firm-level environmental, social, and governance (ESG) structures, national-level carbon market complementarities, and transnational-level international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) climate shaming drive corporate participation in VCMs. Furthermore, we study the pathways through which these multi-level factors affect firm’s participation and show that INGO-led climate shaming can prompt governments to enhance climate regulation stringency, which in turn influences corporate behavior. We also find that national carbon market policies impact corporate participation in VCMs by encouraging firms to strengthen their emission reduction strategies, while corporate ESG structures affect participation through their commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Our study advances the literature in two ways. Theoretically, we conceptualize VCMs as a unique voluntary environmental program and employ a multi-level analytical framework to advance the understanding of the multifaceted behind corporate pro-environmental voluntary behavior. Focusing on VCMs, this article provides a unique perspective to observe the dynamics of voluntary regulation and better understand how the complex interplay of cross-level factors can motivate corporate participation in VCMs. Unlike voluntary initiatives, such as the United Nations Global Compact, that address a broad range of social and environmental issues, VCMs are tailored to emissions reduction and allow participants to quantify their environmental impacts. Meanwhile, VCMs exhibit institutional complementarities with CCMs in terms of participant demographics, market boundaries, and operational regulations. These complementarities contribute to exploring complex interactions between private and public governance. Moreover, VCMs have both market and non-market elements. Carbon credits are tradable among different entities, while the projects developed in VCMs can produce broad socio-economic co-benefits for local communities. The multifaceted features of VCMs suggest that the motivations to participate in VCMs can be complex.

We also provide insights into the mechanisms by which factors at various levels affect corporate engagement in VCMs, thereby offering a more nuanced perspective on the drivers of corporate participation in VCMs. This article leverages causal mediation analysis to elucidate the underlying mechanisms through which multi-level factors influence corporate participation in VCMs. Such analysis allows for a more detailed dissection of the causal pathways, contributing to a deeper understanding of VCM participation dynamics.

Mengying Xie

PhD Canidate, Tsinghua UniversityMengying Xie is a PhD candidate in the School of Public Policy and Management at Tsinghua University. She received my MA from the London School of Economics and Fudan University. Her work focuses on climate politics, transnational governance, and sustainability of China’s overseas investment.

Supply Chains and Political Strategies

Analyzing Firm Responses to the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

This research explores how the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is shaping the political preferences of firms based on their supply chain connections, with some firms strategically supporting the carbon tariff if their suppliers come from “cleaner” states. Using firm-level supply chain data and EU lobbying records, the paper investigates how differing levels of emission regulations across exporting states influence EU-based firms’ stances on the CBAM and related climate legislation.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) charges a carbon price on imported products whose production-related emissions have not been taxed by the exporting states. This mechanism is intended to incentivize more states and regional organizations to develop carbon pricing schemes to obtain the exemption status and reduce emissions in collective efforts. However, the levels of emission regulation development vary significantly among exporting states, as states are either reluctant or incapable of mitigation efforts. Therefore, this paper aims to explore whether EU-based firms’ supply chains with suppliers from different exporting states would shape contrasting political preferences on the mechanism. Conventionally, firms sourcing from foreign partners are considered unconditionally against importing regulatory costs. I argue that depending on the footprints of supply chains, some firms can be strategically supportive to the mechanism: importing firms with suppliers from states with relatively advanced levels of emission regulations (suppliers from “cleaner states”) are more likely to support the additional importing tariff as they are more likely to enjoy the exemption or reduction benefits. Meanwhile, the CBAM poses additional costs to their competitors who partner with suppliers from states with limited levels of carbon regulation development (suppliers from “dirtier states”). On the contrary, firms with suppliers from “dirtier states” are more likely to oppose the CBAM due to the additional carbon price.

Using firm-level supply chain data and the EU lobbying records, the empirical analysis examines whether firms’ reliance on suppliers from cleaner or dirtier states shapes their stances on supporting or opposing the CBAM and related legislation. Specifically, the main outcome variable is on EU-based firms’ political activities using the lobbying and public expressions archived provided by the EU Transparency Register. The paper not only determines whether a firm has lobbied on relevant issues but also analyzes the firms’ stances using text analysis approaches applied to the documents they submitted during the EU’s public consultation sessions. The main independent variable is based on firm-level supply chain information from the Factset Revere Dataset and the state-level emission regulation development indicators based on the Regulatory Indicators for Sustainable Energy (RISE) Dataset provided by the World Bank.

The paper aims to make two contributions. First, as environmental considerations become increasingly integrated into trade policy frameworks, the economic impacts and firms’ reactions have yet to be thoroughly explored. This research, focusing on the CBAM and the lobbying framework in the EU, offers a unique opportunity to examine how firms’ interests interact with the development of international environmental and trade regimes. While firm-level analysis in the IPE literature has extensively concentrated on the United States, the response of firms to climate-related legislation in the EU has not been extensively studied. Second, this paper seeks to enhance the understanding of the political economy of supply chains, with a particular focus on the firm level. Previous research indicates that firms’ preferences for trade policies are significantly influenced by their involvement in international trade, especially foreign production. Yet, this stance does not capture the variation between suppliers, their governing bodies, and the supply chain strategies of competing firms. Notably, firms exposed to international supply chains might now favor a new approach: advocating for strategic trade policies that impose trade barriers to their home markets. This shift is driven by the competitive advantages arising from increasing demands for the dissemination of standards and norms.

Lingbo Zhao

Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science and Social Data Analytics, Penn State UniversityLingbo Zhao is a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science and Social Data Analytics at Penn State University. She studies international political economy, with a focus on the role of firms and supply chain relations in the politics of climate change and economic sanctions.