Can’t Go It Alone: Why States May Not Be Able to Uphold the Paris Agreement

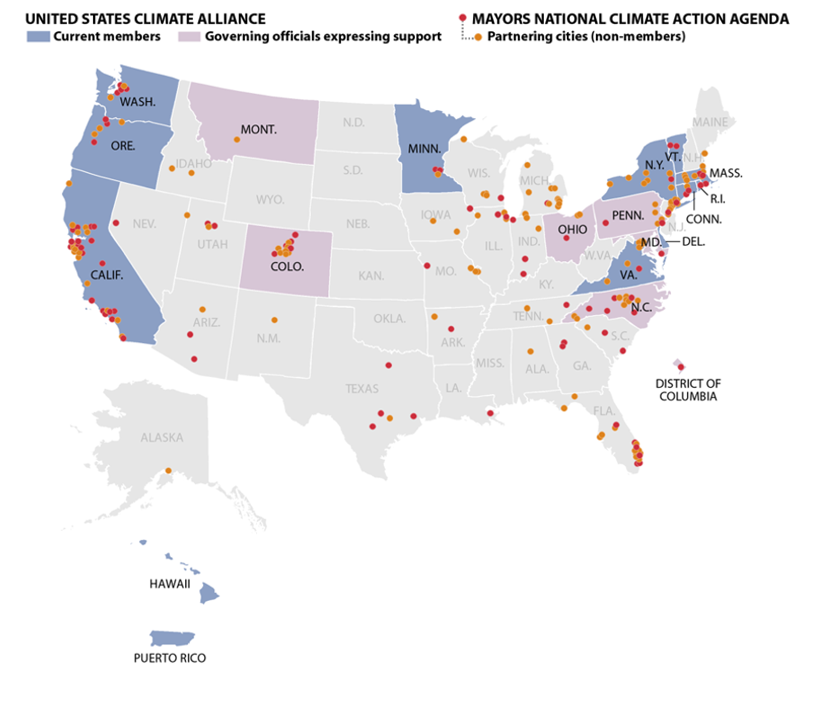

Since President Trump’s June 1st decision to withdraw from the Paris agreement, many states and cities have pledged to take action on climate change, regardless of federal leadership. At least 12 states, and more than 200 U.S. cities have made a commitment to continue in the Paris Climate Agreement, and various coalitions have vowed their support, including the We Are Still In coalition and the U.S. Climate Alliance. Just this week, California Governor Jerry Brown and Michael Bloomberg launched America’s Pledge on climate change, which is an initiative that aims to track and quantify state and city commitments related to the Paris Agreement goals.

The pledges come from usual suspects like Governor Brown, but also from some unlikely players. After Pittsburgh jobs were called out by President Trump as one of the reason to withdraw from the agreement, Mayor Bill Peduto tweeted his support for the Agreement saying, “I can assure you that we will follow the guidelines of the Paris Agreement for our people, our economy & future”.

But when it comes to the legality of state action supporting the Paris Agreement, the devil is in the details. New analysis from the Congressional Research Service shows that such actions by states and cities may be unconstitutional. The CRS reports:

When there is a conflict between state legislation and the foreign affairs policy of the federal government (as expressed in a federal law or international agreement), the Court has deemed the state law invalid under the doctrine of federal preemption.

While generally speaking, states and cities can enter non-binding agreements with foreign governments, Article 1 Section 10, the Constitution does not allow states to individually sign treaties or alliances with foreign powers. Per the CRS Report, the U.S. Department of State has said that these constitutional restrictions only apply to legally binding pacts. It is notable that the Paris Agreement is both non-binding and did not require congressional approval before being signed by President Obama.

So what does that mean for the states that have pledged climate action? While states may not be able to officially join the Paris Agreement, they can act on climate and air pollution within their borders. Through the Clean Air Act, states can pass laws regulating the greenhouse gas emissions for their state. States cannot make binding agreements with foreign nations or express these state actions as an explicit circumvention of a federal decision.

One example of a non-binding agreement, which is likely legally permissible, is the Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) signed between California and China in June of 2017. The MOU stated that both China and California would undertake climate action, but also specified that it was not a binding document saying, “this MOU serves only as a record of the Participants’ intentions and does not constitute or create any legally binding or enforceable rights or obligations, expressed or implied”. According to the report from CRS, “the recent California-China MOU expressly states that its provisions are not legally binding, making it unlikely that this MOU would trigger the restrictions of Article I, Section 10”.

While the MOU between China and California may be permissible according to CRS, other state action may be at risk. Governor David Ige of Hawaii recently passed legislation that would implement parts of the Paris Agreement. Hawaii Senate Bill 559 requires expanded strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and Hawaii House Bill 1578 creates a “carbon farming” task force. This legislation was enacted in opposition to the President’s withdrawal from the agreement with the Senate Bill stating it was created, “support[ing] the goals” of the Paris Agreement, regardless of federal action”.

This language, expressing the purpose of the legislation was to sidestep the federal government’s decision on the agreement, may indicate an overstep by the Hawaiian Government and is legally on shaky ground. Although prior to Paris, many states have enacted policies that support a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, there is a legal vulnerability associated with the language in the Hawaii legislation indicating that this regulation is in response to the Paris withdraw.

As states continue to express support for the goals of the Paris agreement, it is also worth noting that these are not pledges agreed upon by the international community. These one-sided commitments are not signed or approved by foreign nations, another point that supports the constitutionality of state promises.

Even though cities and states committing to the Paris Agreement may not have legal backing, the message these promises send to the international community is still a good one. While states may not be able to “officially” pledge to the Paris Agreement, state actions can go a long way in reducing carbon emissions across the U.S., despite an absence of federal action.

Mollie Simon

Senior Communications SpecialistMollie Simon is the senior communications specialist at the Kleinman Center. She manages the center’s social media accounts, drafts newsletters and announcements, writes and publishes content for our website, and regularly posts to our blog.