How Interdisciplinary Teaching Becomes Climate Action

When 35 students from five Penn schools analyzed real DOE industrial decarbonization projects, they discovered that net zero is a systems challenge requiring fluency across disciplines. Their work shows why interdisciplinary teaching is climate action—and how it builds the human capital the clean energy transition demands.

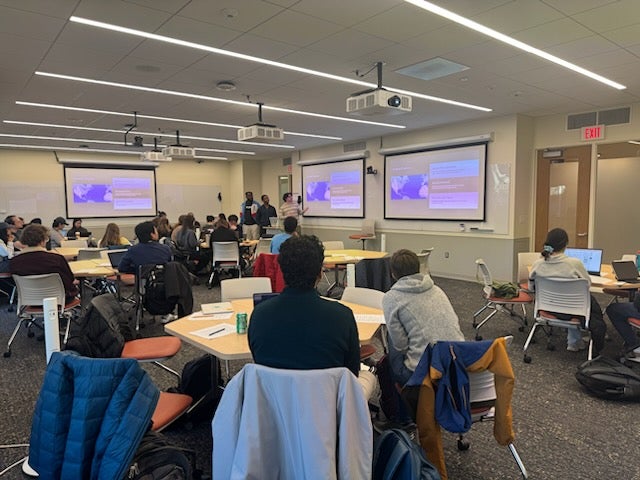

In the Penn graduate course ENMG 5400: Clean Energy Deployment to Achieve Net Zero with Jennifer Wilcox, 35 students from Engineering, Wharton, Design, Arts & Sciences, and Law worked in interdisciplinary teams to analyze ten industrial decarbonization projects—spanning steel, cement, glass, chemicals, copper recycling, and food manufacturing. Their work illustrates why teaching is climate action—and how building human capital accelerates real-world impact.

Thousands of companies have committed to net-zero targets, with many following the Science-Based Targets initiative and developing detailed plans for Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Throughout the semester, the course centered on the question that now defines the net-zero transition: how do these plans move into practice? The answer is clear—achieving net zero depends not only on technologies, but also on people, systems, and interdisciplinary fluency.

The goal was to understand what it really takes to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors from multiple lenses. Students’ analyses affirmed the idea that teaching is not peripheral to climate action; it is climate action. The work builds not only knowledge but the human capital needed for this decisive decade.

Students began by grounding themselves in the engineering fundamentals of each project. Whether the technology involved an induction furnace for steel reheating, a hybrid electric furnace for glass production, an electrochemical cement process, advanced copper recycling, or electrified process heat in food manufacturing, they found that the technical pathways were challenging but achievable.

The more difficult questions emerged when students examined the full system surrounding each project. They discovered that a project’s location can reshape its risk profile—shifting technical, financial, and social conditions even when the technology stays the same. Financial analyses revealed how project economics can make or break deployment, especially for first-of-a-kind technologies that rely on tax credits, grants, low-cost Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), or government cost share. Teams saw that a single shift in policy or funding could alter a project’s viability overnight.

Students also looked closely at the communities hosting these industrial facilities. Using tools such as EPA’s EJScreen and the federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, teams explored environmental and socioeconomic burdens in regions like Holyoke, MA, Modesto, CA, Freeport, TX, and Shelbyville, KY. They recognized that community benefits plans only matter when projects genuinely reflect local priorities and needs. And, as with the financial analysis, students found that aligning projects with community priorities and delivering tangible economic and social benefits made deployment far more viable in a given location.

What ultimately made this class powerful was the interdisciplinary method. Engineers mapped emissions pathways and energy flows. Law students examined permitting, liability, and regulatory frameworks. Students from planning and design interpreted spatial inequities and community context. Wharton and Arts & Sciences students built financial models, policy analyses, and justice-centered assessments. The best insights always arose at the intersection of these diverse perspectives. The diversity of the class was not only disciplinary but global, with students from roughly ten countries bringing international perspectives that sharpened every discussion and underscored that the energy transition is a worldwide, context-specific challenge. Again and again, students found that some regions offered far lower deployment risk than others—whether due to policy stability, carbon-pricing structures, workforce depth, or infrastructure readiness—an insight that now frames their final team project.

One lesson students took away is that industrial decarbonization is a systems challenge. No single discipline holds all the tools required to deliver net zero. The energy transition demands technical rigor, financial literacy, policy fluency, legal understanding, and an appreciation of place and people.

Universities have an essential role to play in preparing the workforce that will lead, regulate, finance, and implement this transition. Educators help students close gaps, develop judgment, and accelerate readiness for impact—because time is running out.

No one course is enough. But experiences that bring disciplines together around real projects, where technology, finance, permitting, justice, and community all intersect, are indispensable. They cultivate the habits of mind and practice that future climate and energy leaders will need.

This class demonstrated that interdisciplinary teaching does more than convey information. It builds the human capital required for the decisive decade ahead.

Course Instructors and Students:

Jennifer Wilcox1,2,3, Katie Harkless2, Haley McKey2, Hélène Pilorgé1, Shrey Patel1, Makenna Damhorst5, Mayesha Ahmed5, Ji Yoon Bae3, Brian Buhr6, Meixi Chai3, Nuo Chen5, Conrad Cross6, Xiaoyue Cui3, Lena Gandevia4, Megan Grapengeter-Rudnick5, Maya Halma5, Qinming Hou3, Brandon Licata5, Dianyi Lin3, Jinyi Lin5, Yujia Liu3, Nechama Lowy5, Hanzhong Luo3, Stuti Mankodi5, Tyler Maynard3, Lindsey McMackin5, Rhazy Mohammed4, Likhwa Ndlovu1, Tosa Nehikhuere4, Shu Neoh5, Islam Osman4, Navya Pandey3, Nabila Safitri5, Aryaman Shah1, Yiming Shao5, Ananjai Tamboli1, Lia Teitelbaum5, Hong Wei3, Zixuan Xiong5, Yuan-Ching Yu3, Xuhan Zhao3

Affiliations

1U Penn, School of Engineering and Applied Science

2Kleinman Center for Energy Policy

3U Penn, Weitzman School of Design

4U Penn, Wharton School of Business

5U Penn, School of Arts and Sciences

6U Penn, Carey School of Law